Impressions of New York City Ballet's Fall Season 2014

Visions of Fall Dance Over Our Heads on to The Nutcracker Stage

Lincoln Center, New York City

September 23 – October 19, 2014

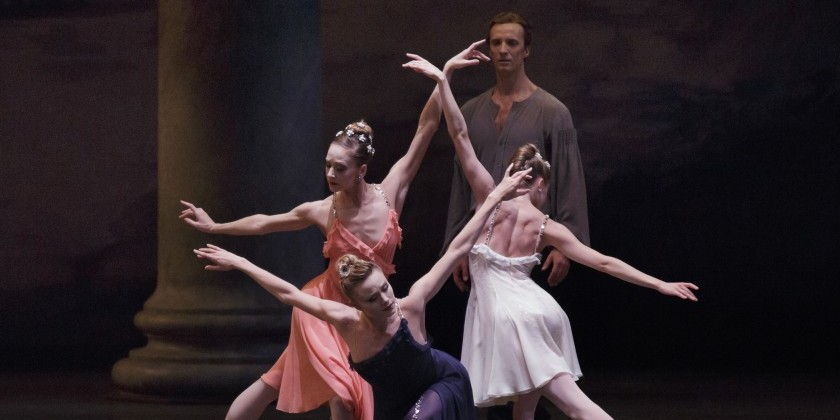

Pictured above: NYCB in Peter Martins' Morgen at the 2014 Fall Gala, with costumes by Carolina Herrera. Photo: Paul Kolnik

As New York City Ballet enters its run of The Nutcracker (that began on November 28) it is a good time to look at the dancers who will be Sugar Plums, Dewdrops, Cavaliers, and Candy Canes to see how they mastered the fall season’s repertoire. It is interesting to note that several principals are involved in musical productions in NYC and abroad. One hopes they will come back with new perspectives and refreshed energy.

The fall season featured a program with four new works by different choreographers in collaboration with various fashion designers and a re-envisioned costume design by Carolina Herrera for opening number Morgen, originally presented in 2001, by Peter Martins. Under the supervision of City Ballet’s costume director Marc Happel, the enterprise was in caring hands, and a fiasco, as with the recent collaboration with Valentino, was avoided. Herrera’s timeless tunics draped each dancer elegantly and the fabric flowed with ease. Enhanced by a selection of Richard Strauss’ Songs for Soprano (Jennifer Zeitlan) and Orchestra (under Andrews Sill), the dancers navigated around columns (by Alain Vaes) in Martins’ evocation of Arcadia, lit by Mark Stanley. Corps member Ashly Isaacs (in white) joined principals Rebecca Krohn (glorious in a midnight blue, off one shoulder number) and Teresa Reichlen (in a coral beauty of a dress). Zachary Catazaro, Chase Finlay, and Russell Janzen lent their gallant and ardent support. I appreciated the work’s good looks, but I longed for greater dynamic range and a change from Martins’ relentless repetition of the pas de deux form. Although the women changed partners, Martins missed the opportunity to introduce different groupings.

Another sextet continued the program. Clearing Dawn, a premiere by NYCB corps member Troy Schumacher with music by Judd Greenstein, got the costume treatment from none other than Thom Browne. Grey school uniforms impeding freedom might make for a nice metaphor, but if that was the idea, it was not carried out choreographically. An effective gimmick was the sudden removal and hoisting of the cast’s overcoats that then hung suspended above the proceedings. Ms. Reichlen performed double duty that evening and joined Ashley Bouder, Claire Kretzschmar, Georgina Pazcoguin, David Prottas, and Andrew Veyette.

Zachary Catazaro proved to be a fine partner for Gretchen Smith in Liam Scarlett’s Funérailles to music by Franz Liszt played passionately by pianist Elaine Chelton. Clad in a gorgeous gold-embroidered frock, he swirled, threw, and caught Smith, who emerged at one point or another from the beautiful sea of fabric surrounding her. Courtesy of Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen, the design might have been too much of a good thing and left the dance a secondary participant.

“Much Ado About Nothing” should have been the title for Mary Katrantzou’s design for choreographer Justin Peck’s Belles-Lettres. The appliquéd letters on unitards washed out under the stage lights, and from my orchestra seat, the costumes looked as if the male dancers wore camouflage fatigues. Beautifully detailed in pictures up close, the design work did not pay off for at least three-quarters of the audience. It’s an easy trap to fall into for a fashion designer who has not yet considered the wonders of the stage. The choreography was often intricate and yet remained decorative. It got interesting when Peck played with group forms and created community. A lone male spirit (Anthony Huxley) added spice to the four couples. Cesar Franck’s Solo de piano avec accompagnement de quintette à cordes was beautifully played by pianist Susan Walters and led by conductor Daniel Capps.

Pictures at an Exhibition is a deservedly well-known composition by Modest Mussorgsky. Born in 1839, he was part of a group of composers known as “The Five.” It is his original piano work from 1874 and not the popular orchestration by Ravel (1922) that was used for a new ballet. What a joy to rediscover the expressive depth of this score and, while listening to pianist Cameron Grant, to realize that Ravel omitted a movement. Alexei Ratmansky has made (far too) many ballets to music by Shostakovich. Here he departed from his usual pattern and instead of Soviet-based glorification, he went backward in time to celebrate Mother Russia. Although the music was the outstanding ingredient, the dance was far more interesting than anything Ratmansky has delivered at ABT. There was a projection design by Wendell K. Harrington that played with images of a Kandinsky painting, something Mussorgsky obviously would not have seen.

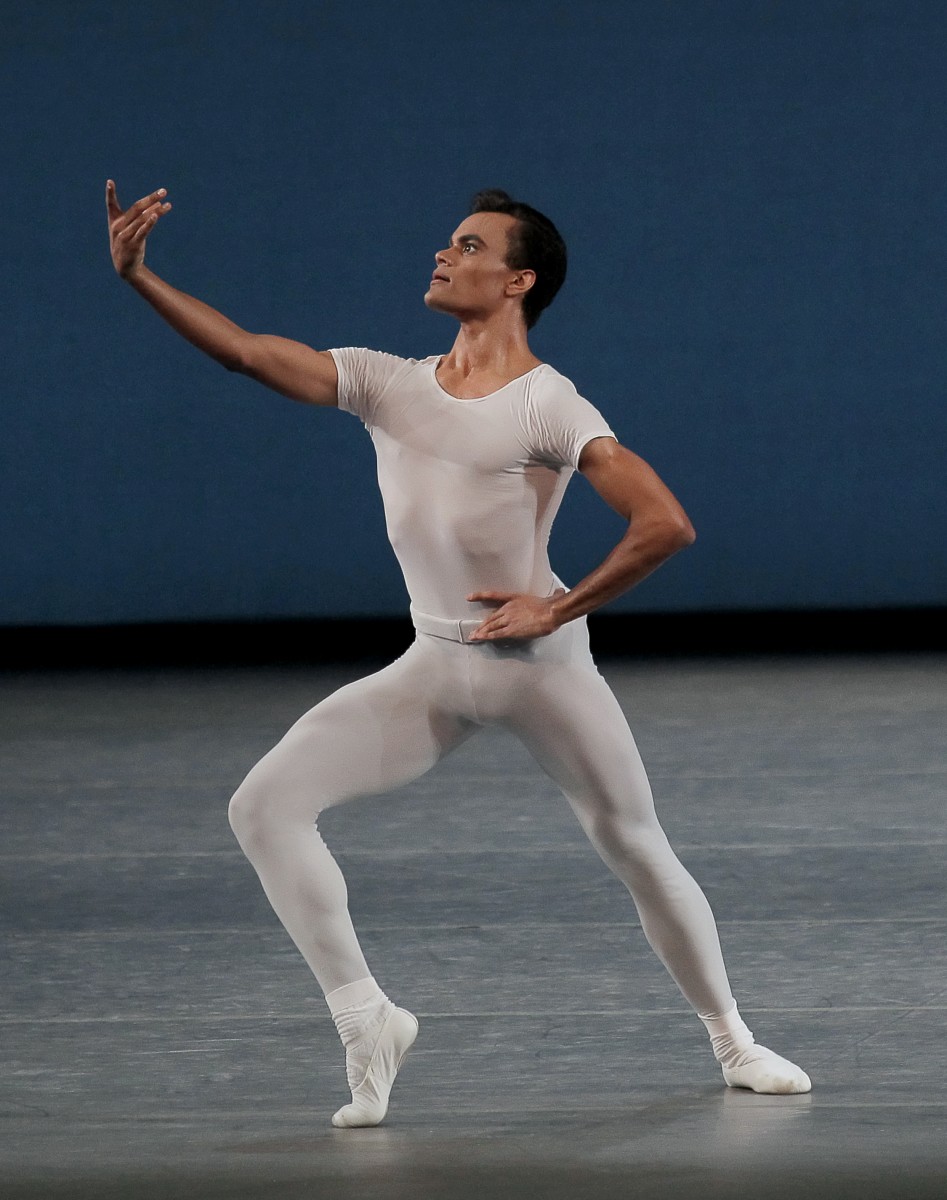

Musical Romanticism introducing modernism paired with scenic abstractionism gave Ratmansky a wide playing field, and he used it to his abilities. A score that provided such phenomenal riches gave root to some dynamic shading and high-octane dancing by Sara Mearns and Amar Ramasar. Solo passages (for Tiler Peck and Gonzalo Garcia), a traditional pas de deux (for Wendy Whelan and Tyler Angle) as well as duets that strayed from the “man supports woman” formula (for Abi Stafford and Joseph Gordon) plus group sections for the ten-member cast kept me visually engaged for most of the ballet. Gretchen Smith and Adrian Danchig-Waring completed the fine cast. The imaginative and effective costuming by Paris couturier Adeline André added color to the palette. Loose beige outfits for the men with bold color swatches on the chest and a corresponding detail on the leg were attractive. There was iridescence to the costumes that might be from a thin layer of sheer material sewn over the beige base fabric. The ladies wore short painted tunics, some more colorful than others, each embodying an idea of a painting.

If the evening of new dances left me wanting choreographically, I was rewarded by Mr. Peck’s other recent creation, which premiered in May to an original score by Sufjan Stevens. The large cast for Everywhere We Go was listed hierarchically in the printed program with seven principal performers, six soloists, and twelve corps members. Yet it was the encompassing sense of community that prevailed in this work. Three men were coupled with male shadows. Each gesture done vertically was reflected horizontally by the supine shadows on the floor. With arresting imagery that evoked a multi-layered world, Peck commanded my attention. The males clad in black with grey chests, danced with dark intensity. Women, whose costumed upper halves were striped (think sailors) and whose white leggings and pointe shoes cut, circled, and defined the space, lighted up the surroundings and the mood. A red ring around each dancer’s mid-section reminded us that they all were the same species and should get along. Former NYCB ballerina Janie Taylor was responsible for the strikingly handsome costumes. The set design by Karl Jensen was fantastic: Cutouts in the backdrop let light come through in patterns, and then, the backdrop shifted and different cutouts emerged. Patterns changed periodically and introduced a new mode, an unknown room, a higher plane, a darker place; it was a most effective change of scenery.

I was floored by the significance of a pas de deux performed by Rebecca Krohn and Adrian Danchig-Waring. At times during their duet, other cast members were in group formations. Krohn left her partner momentarily, created contact with the group, and then returned to him. He was a loner; she his link to the world outside their relationship. This interplay occurred several times before he felt secure enough to enjoy a moment being part of the community. The hierarchical structure of ballet was pulverized: The principals were not performing in front of a supporting cast, instead we were given a glimpse of two people’s relationship the choreography focused on. When Krohn left him and Danchig-Waring lifted other women, we knew that she, who briefly returned to check on him, had prepared him to be alone or within a group. She, though, needed to move on. Now, I may have read into things and interpreted a basically abstract ballet in which Peck might have had something else in mind. But that was the beauty of this work.

Everywhere We Go with its myriad of looks, plethora of movements, and endless possibilities was transporting to watch. It made one listen and dream. It was long and not every section as evocative, but after seeing it twice, I pined to experience it again. Other than Krohn and Danchig-Waring, it was the presence of Amar Ramasar, Andrew Veyette, Sterling Hyltin, Teresa Reichlen, and once again Ashly Isaacs that propelled the ballet. But here I have singled out only the principals in a momentous group effort for which everyone truly deserved applause and praise.

I applauded Ashley Bouder for her abandon as Firebird, especially after having expressed my hope for that moment in my last review of her dancing. I cheered for Taylor Stanley in Square Dance. He is a fine dancer, and I keep my fingers crossed to see him in other repertoire and new works as well. I delighted in seeing Jerome Robbins’ The Concert. Led by Sterling Hyltin, Andrew Veyette, and Lydia Wellington, the work has not lost any of its humor and poetry. The dancers were in great shape. After saying goodbye to the marvelous Jenifer Ringer during the winter season and now farewell to Wendy Whelan, the company has renewed itself simultaneously. One hopes for the return of the company’s Sleeping Beauty Ana Sophia Scheller, who has been sidelined for the year with injury.

Next to Krohn, Bouder, Kowrowski, Mearns, and Reichlen, the upcoming Nutcracker casting of Sugar Plums for the first two weeks includes Erica Pereira and Brittany Pollack. Based on what I saw during the fall season, Pollack deserves her chance. Ashley Isaacs, Lauren King, Abi Stafford, and Tiler Peck join as Dewdrops. Zachary Catazaro is the only not-yet principal as Cavalier. And soloist Sean Suozzi gets to display pyrotechnics as Candy Cane on some nights and on others will invite you to his magical land of sweets as the mysterious Herr Drosselmeier.