A Tale of Dance in Detroit: Pioneers and Natives

Weighing In On The New Dance Frontier

Contributor Trina Mannino grew up in the Detroit suburbs where she also trained as a young dancer.

In the last decade, Detroit has captured national interest in splashy news stories.You may have watched the Anthony Bourdain special in which he compared the city to the nuclear ravaged Chernobyl. You may have come across images of derelict banks, warehouses, and once grand homes, now delipidated. These strangely romantic images, simultaneously highlighting demise and possibility, helped spark the term “ruin porn.” Yet, publications like The New York Times Style Magazine and Elle have shown a Detroit filled with bespoke leather goods, artisanal coffee, and hip, young creatives, captivated by the potential. Is this financially insecure city — rife with a history of corruption — the new artistic promised land? In a 2013 New York Times article, by Courtney Balestier, contemporary visual artists and curators seemed to think so. Even as Detroit entered bankruptcy, crowds flocked to art shows and private investment was described as at an "all-time high."

But what about Detroit's dance community?

New York choreographer Jody Oberfelder, who grew up in Detroit, recalls a visit to her hometown last year. “We were staying at the Westin, and there were these magazines in the lobby that made Detroit look so glamorous.” Meanwhile, driving through her old neighborhood, she and her father witnessed a profusion of rotted, abandoned homes — and they weren’t romantic. Unfortunately, desolate streets like Oberfelder’s abound.

Recently, Brooklyn’s Galapagos Art Space announced its plan to move to Detroit, attributing New York’s skyrocketing rent costs as a major factor. Artistic director Robert Elmes and his partner, the choreographer Philippa Kaye, bought not one, but several buildings in Highland Park (a small enclave surrounded completely by Detroit) as well as in Detroit proper. Galapagos’ impending move has sparked controversial questions regarding the state of Detroit’s artistic landscape.

There’s always been a robust performance community in this city. In the mid-twentieth century, Detroit teemed with artistic energy, notably in the African-American neighborhood Paradise Valley. Detroiters would go to “the Valley” to see legends like Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker perform while they were in town. The vibrant entertainment hotbed, largely demolished due to the construction of the I-375 and I-75 highways, preceded Motown, Detroit rock groups like The Stooges and The White Stripes, and the world-renowned techno and house music scene that the city now boasts. Today, Detroit also hosts DEMF, the world’s first and largest electronic music festival.

Artists and organizers who have lived in Detroit for decades, or all of their lives, have made lasting contributions and continue to do so. Yet, creativity has often been overshadowed by violence and scandal: from the Race Riots of 1967 to former Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick’s 2010 indictment for 24 federal crimes; from the city’s shutting off water for the thousands who didn’t pay their bills last summer, to only recently emerging from bankruptcy in December.

Can Dance Empower a City?

Dancer Haleem “Stringz” Rasul believes Detroit’s time to shine is now. “Through dance you can be a major changer in this city. Dance is that strong because you show through action.”

The 37-year-old lifelong Detroiter recounts when he began his dance and design company Hardcore Detroit in 2001, “I was going against the grain...I was initially focused on graphic design, but something deep inside me was telling me to include dance, and it’s the best thing I ever did.”

Hardcore Detroit, performs Jit, a revived dance style conceived in the early 1970s by street gangs who lived through the Race Riots of 1967 and then the drug culture that later engulfed the city. Dance battles were a way to channel frustration and violence. Characterized by furiously fast shuffling, Jit looks as if the performer is trying to knock his feet out from underneath himself as he moves. The dance was popularized by three raucous brothers (Tracey, Johnny and James McGhee) who were the core members of the “Jitterbugs” (not to be confused with the Jitterbug form of swing dance).

“The Jit documentary I made, ‘Pioneers of the Jit: The Jitterbugs’, should have already existed,” Rasul says, frustrated that more people aren’t already familiar with the 40-year-old Detroit dance form, which today includes more floor work and is often danced to techno and house music. On the other hand, he admits, because of his film, “We now have everyone’s attention.”

Since the “Pioneers of the Jit” premiered in May 2014, it sold-out at the Freep Film Festival at MOCAD Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit in March. Rasul plans to travel to Zimbabwe for a “Jit exchange” program in May and was recently invited to teach a semester-long Jit class at Eastern Michigan University in the fall.

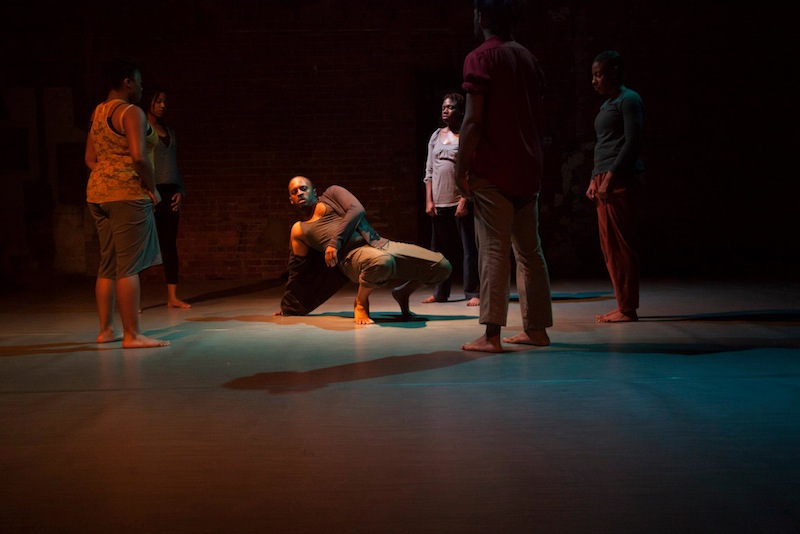

Jennifer Harge, an emerging dancemaker, agrees with Rasul about the power of dance. She is currently touring a dance-theater piece that examines the nature and treatment of death in African-American communities. The work, the line between heaven and here, has been successfully presented in Detroit twice (at the industrial Jam Handy space and ArtLab J) as well as outside the city in the Midwest Rad Festival and at the Saginaw Arts & Sciences Academy. “I think many choreographers in Detroit are making work about what they see around them, and the work speaks to the city.”

Biba Bell, a California native who performs, choreographs and teaches in the dance department at Wayne State University, points out that the media gloss is glaringly different than reality. “Its potential is contagious, but ... people get their hands dirty and work,” she says, mentioning the immense effort it takes to produce dances and train without a large pool of resources.

“Detroit is a funny place. It feels a bit country to me. That’s partially due to the sheer amount of empty space. But at the same time, it has a cosmopolitan vein...The level of the institutions here are phenomenal,” Bell says as she lists the Detroit Institute of Arts, the dance company ArtLab J, and MOCAD. (These organizations are merely three of the 1,800 “cultural assets” inhabiting the tri-county region. Others include the Charles H. Wright Museum of African History, Detroit Opera House, and the Historic Scarab Club of Detroit. *See the Kresge Foundation’s “Creative Vitality in Detroit: The Detroit Cultural Asset Mapping Project.” )

“It’s a wild place. You won’t get bored.” Bell says.

The city’s duality is what partly drew Elmes to relocate both his organization and family. “I was amazed at the quality of fallow space — how much unused space there was that seemed like it could be put back into productive circulation almost immediately,” Elmes says. “For a New Yorker, it was like hitting the lottery of live/work dreams.”

Detroit critics of the Galapagos Art Space move are wary, asserting that the transplant must be sensitive to the individuals and organizations that have come before. “Certainly there are chips on shoulders. The city can be leeched upon in a way by [people] drying out resources. There’s such a history of corruption and exploitation,” Bell says. (Though, of course, none of the corruption and exploitation was caused by artists.)

Oliver Ragsdale, Jr., the president of The Carr Cultural Center, exhibits concern when speaking about Galapagos. The Carr Center, located in the historic Harmonie Park building, offers visual art, theater, dance, and opera programming — a similar roster to Galapagos’ artistic fare, though with a focus on the African-American community. While Galapagos has purchased nine spaces in the area, The Carr Cultural Center is still striving to purchase its current building to ensure that the organization can contribute to the area for decades to come. In the past four years, the center has revved up its dance offerings, partly due to demand, as well as the success of a pilot dance education partnership with the Cranbook Educational Community, which allowed young students to explore dance and the science of motion and “the African dance canon.” The institution will also be opening a public space that can be arranged as a mid-size theater in addition to a rehearsal studio upon completion of its renovation next year.

Wary of the pattern of pioneers encroaching on natives, Ragsdale, a Pittsburgh native with an over 20 year commitment to the arts in Detroit, says: “I’m concerned that the people who have been here for 25-30 years will be pushed aside because everyone is excited by a new idea.”

He credits the “native” artists who set up shop in Detroit prior to the economic downturn and bankruptcy. The city is now feeling positive effects from their contributions. Does the Galapagos move portend gentrification in Detroit? Will the diverse neighborhoods of this city suffer the fate of Soho, once a rich artistic neighborhood that is now a mass of elite shops and chic dwellings? Organizations are making strides towards preserving Detroit’s diversity.

Isn't there room for more spaces and people? If newcomers move to Detroit to help create or enjoy a more vibrant arts community, does that mean the death of the original spirit of the city? Erika Stowall, a native Detroiter who teaches dance at a local charter school and directs her company Red Wall Dance, believes more theaters are a necessity in order for dance to flourish. She expresses dismay with the limited availability of places where she can currently present her work. There are a handful of studios and large proscenium stages but nothing in between. “I’m thankful an organization [Galapagos] of this size is coming in.”

“I think competition is healthy, especially in a city,” Bell says. “It’s important to have options and not have everything run by one set of hands or board. Curatorially, it’s important to have diversity.”

How does Galapagos plan to address the needs of the community while not stepping on the toes of those who stuck it out all these years? The Galapagos team is receptive to discussing concerns, seeking to work with locals instead of against them. Elmes met with local designer and blogger Dylan Box in response to Box’s initial criticism of the move in which he accused Galapagos of accelerating gentrification and “bragging" on the deal. Since their meeting, Box has taken a warmer stance towards Galapagos and Elmes.

“The existing community of artists and thinkers was the most important factor in deciding on Detroit,” Elmes says.

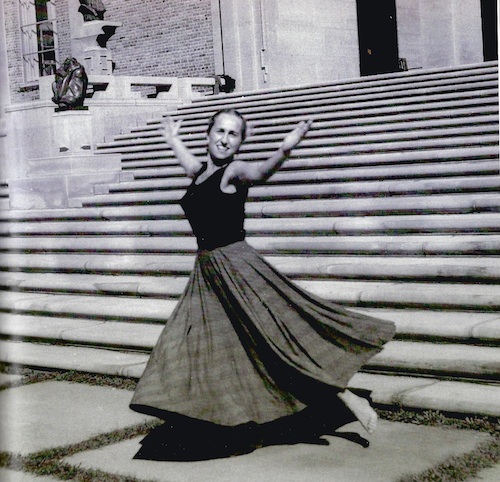

One colorful member of the community is Harriet Berg, a 90-year-old historian, educator, and choreographer, who “holds the key to the city’s dance history.” Growing up in Detroit, she has witnessed dance ebb and flow. The electrifying Berg began dancing at Wayne State University — one of the country’s oldest college dance programs founded in 1927 — and then went on to run several companies as well as direct the dance program at the Jewish Community Center of Metropolitan Detroit from 1959 to 2009.

Berg always looked forward to New York companies — from José Limón to Dance Theatre of Harlem — visiting Detroit, exposing internationally-acclaimed troupes to both her dancers and audiences. “I used to tell my dancers, ‘you are the modern dance of Detroit, so you need to be in touch with the people who are creating American modern dance,’ ” she recounts.

Several Detroiters went on to join Twyla Tharp, Martha Graham Dance Company, Alvin Ailey American Dance Company, and the José Limón Dance Company. Berg hoped that they would would return to Detroit to create a training ground, one that was comparable to Juilliard and other elite conservatories. But as Detroit’s economy and population declined with a surge in violent crime in the 70s and 80s, private dance schools and companies moved out to the suburbs, making Berg’s vision unattainable.

In recent years, Berg has had the opportunity to champion several promising choreographers who are calling Detroit home, including Bell, Harge and Stowall, among many others. She speaks of them with great admiration, describing them as cultural ambassadors of the city.

With the addition of new spaces in 2016, there will be a surge of performances for Detroiters and suburbanites to enjoy. But are people actually coming now and will they attend unfamiliar artists’ shows or venture to new venues?

Bell believes audiences are already there and growing. Artists in Detroit, just as here in New York, have to think outside the box by, “cultivating a different audience and not dancing within only a dance community.” This February, the choreographer performed a series of solo performances in her own apartment in the Mies van der Rohe-designed village of Lafayette Park. Her work was critically well-received and sold out on all six nights, leading her to reprise the program at the prestigious Cranbrook Institute of Arts in nearby Bloomfield Hills.

Oberfelder, who still has many friends and family in the region, believes people will frequent these spaces and their neighborhood establishments for their “cool factor.” “It will be similar to food scene in New York,” the choreographer posits. “Everyone has to try the hottest restaurant.”

Ragsdale says that for several years he observed a steady decline in artistic vibrancy but thinks “it’s changing as we speak. We’re on an upswing.”

There are countless questions beginning with if, when, and how that are related to the future of Detroit’s performance community. It can’t yet be predicted the exact amount of works that will be produced and their quality, nor do we know the number of people who come to see them. Even if the city sees an abundance of art in the next decade, will that surge of creative outpouring encourage investors, politicians, and community heads to lead with courage and integrity?

“There is nothing stable about any city in this day and age,” says Bell. “That identity is in flux constantly.”

Unpredictability, resilience and audacity make up the Detroit spirit. The dance artists of Detroit champion their imperfect city as it enters this new phase, and will stand by it, if it stumbles.