Impressions of Anna Azrieli and Stuart Shugg

In Gibney Dance's DoublePlus Series

Dear Washing Machine, Long Night and Averaging

Presented by: Gibney Dance, 890 Broadway, New York, NY

December 10, 2014

Dancers: (Dear Washing Machine, Long Night) Stuart Shugg, Hadar Ahuvia, TJ Spaur

(Averaging) Anna Azrieli, Talya Epstein, Evvie Allison, Megan Kendzior, Katy Telfer

Choreography: (Dear Washing Machine, Long Night) Stuart Shugg

(Averaging) Anna Azrieli

Late in 2011, Australian dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker Stuart Shugg, then in his mid-twenties, became the last performer to be taken into the Trisha Brown Dance Company before Ms. Brown retired from the stage. A year later, he was being interviewed at length (without the peg of an upcoming performance) in The New York Times by Alex Witchel, longstanding cultural reporter for the paper, who went out of her way to confess that she doesn't go to see much dance. When Witchel interviews artists of any medium, she also tends to train her sights on big stars. (Her previous dance story was a large interview-feature with Twyla Tharp, back in 2006, for The New York Times Magazine.)

Was Mr. Shugg a potential star? I squirreled away his name until I could see him perform firsthand, which I did recently, on a program in the “DoublePlus” series (“A Series of Artists Curating Artists”), shared with the dancer-choreographer Anna Azrieli, a native of the Soviet Union who was reared in New York.

Dear Washing Machine, Long Night

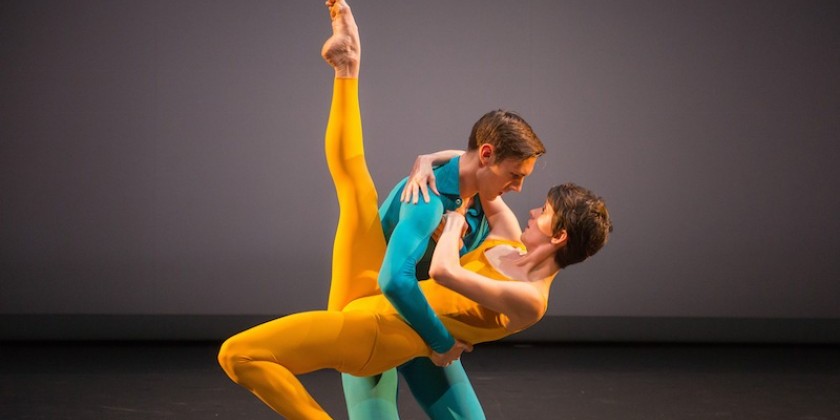

Although Mr. Shugg's new dance trio with film, Dear Washing Machine, Long Night, could win a prize for the worst title of a dance work in 2014, his own dancing is wonderful, a kind of brilliant, full-bodied calligraphy on space. His choreography for himself and colleagues Hadar Ahuvia (also a choreographer) and TJ Spaur — both, like Mr. Shugg, exponents of what I think of as the flexible-wire school of postmodern dancing — isn't at the same level of interest, though it offers lively phrase-making ops for the cast and some arresting architectural patterns for the audience. By “architectural,” I mean to invoke structures and relationships that develop principally from ecological concerns, from considerations of how it serves rather than how it looks — architecture as it is taught in certain cutting-edge grad programs now — rather than the ancient tradition of self-contained, independently conceived buildings that, say, Lincoln Kirstein was thinking of when he used “architecture” as a reference for choreography half a century ago.

More important to many young dancemakers today than beautiful or powerful invented or re-imagined structures is how a dance feels momentarily to observe and how its porous, moment-by-moment procedures reflect the process by which it was made. The elements that, traditionally, help an audience to perceive and remember dancing are no longer reliably present. It takes effort, sometimes tremendous effort, to mentally rewind the events of many contemporary dances and suss out an organizing design, if, in fact, there is one to suss.

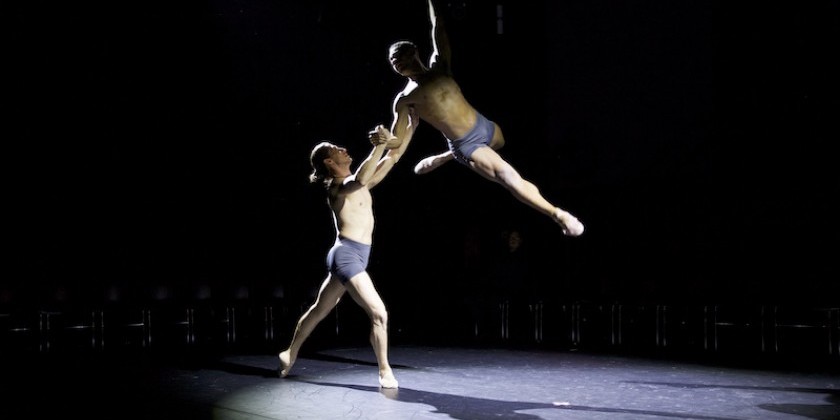

Dear Washing Machine opened with a solo, divided into four or five sections of contrasting dynamics and physical levels, for the choreographer. Mostly, he advanced with sustained and satiny momentum, imperturbable as a buddha, as his long bare feet, paused, melted into the floor, executed a line of arabesque hops, engaged in extreme shifts of weight, squatted, and otherwise demonstrated his skills as an unusually gifted biped, all on the diagonal. Handsome, tallish, lean, beautifully proportioned for dance, entirely authoritative in his display of steps and gestures, and characterized by that uncanny sobriety, he was entrancing to watch.

On three screens above him from time to time were projected fragmentary documentary films (by Shugg and filmmaker Matthew Salton) of resolutely undramatic scenes, such as an uninhabited beach. I think there were natural sounds occasionally, too, but my memory may be tricking me there. (No composer or sound designer is credited in the program.) Eventually, Ms Ahuvia and Mr. Spaur — dressed, like Mr. Shugg, in yogawear of neutral hues and also lean and well-proportioned, though without his intrinsic authority as a dancer — entered and, precisely and unemotionally, began to execute movement phrases over on the side, near the former factory's columns. Sometimes, these colleagues interacted with Mr. Shugg — silently conversing in a kind of artifactual ettiquette — and sometimes they interacted with one another; and, sometimes, they simply functioned as phrasemaking independents in a sort of fugue state, slanting their bodies against the theater's wall of mirrors. The legacy of Trisha Brown was visible, although not her heralded knack for magicking pedestrian materials (at least not yet).

One element I noticed in both works on this program, especially as I was seated in the first row, was the condition of the dancers' bodies. Dance critics aren't supposed to discuss dancers' bodies, so I won't mention that Mr. Spaur performed with neatly groomed facial hair, Mr. Shugg with a Bogartian five-'o-clock shadow, and Ms Ahuvia with little meadows of hair in the axilla areas, showcased by her sleeveless top.

Averaging

Issues of The Body, though, also figured in Anna Azrieli's structurally intricate yet ultimately visceral quintet, Averaging, which followed intermission. Unlike Dear Washing Machine, which seems still to be in process of creation, Averaging has the look of something worked through, resolved. A dyad (the chorographer and the dancer Talya Epstein) are positioned center stage, where, now seriously, now with deliberate laughter or vocalizing, they adopt symmetrical poses and gestures and suggest dramatic relationships, while a trio (Evvie Allison, Megan Kendzior, and Katy Telfer), perambulating in synch, function as a little corps de ballet, pursuing asymmetrical pathways around their featured colleagues and otherwise serving as their living frame.

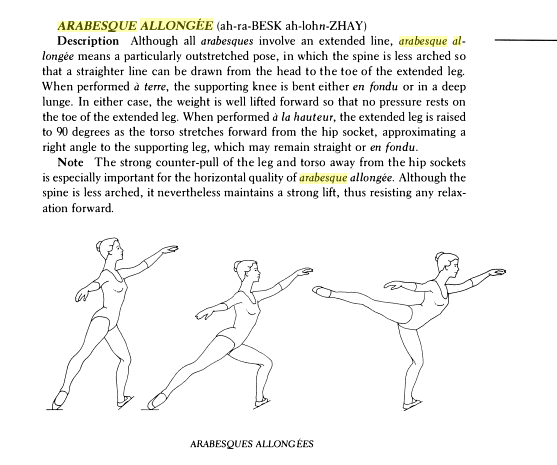

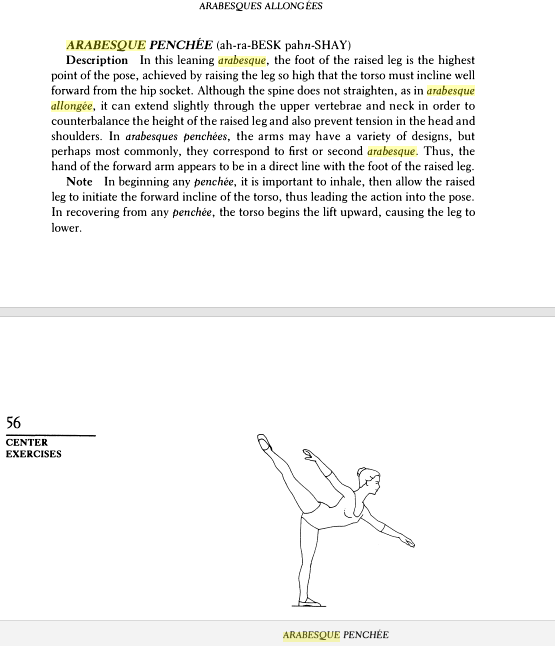

At first, an audience member is struck by the glossy-magazine, shining-hair gestalt of the performers, attired in stylish tops or jewel-colored terrycloth dresses (designed by Connor Voss). Then, that's converted to a more mass-market image. It's not clear what the vocalizing is supposed to accomplish, but it's startling, a theatrical strategy, and it pretends to a kind of intimacy between the performers and the audience—the dancers “letting it all out,” that kind of intimacy. Eventually, one by one, the five dancers end up imbibing water from plastic glasses and spitting it back in with a determination that made the sounds of the spitting, effectively, the dance's score at that point. The starring dyad begins this waterworking in arabesque allongée, which, when the cups and water are added, is deepened into something like arabesque penchée for the spitting part.

At first, the action and sound of the tipping-bird sippers were novel and cute; soon, however—when one realized that the orchestrated sound of individuals sipping and spitting and sipping and spitting closely resembles what one hears in a public toilet at the end of a long movie — the work wasn't so charming; depending on one's associations, it could become nauseating. (What mattered to the choreographer, one supposes, isn't which response it stimulated in members of the audience but whether a response was stimulated period.)

A memorable evening — but would it have been memorable if the bodily issues had not been present? For both dances seemed to have inherited something, at the least, of the intellectual focus on “The Body,” original to Europe, which writers and performers in the United States began to probe during the 1970s and with which some are still engaged if not mired. The idea in dance, as I understand it, is to give the dancing body—so often disciplined (or over-disciplined) by the performer in order to accord with an aesthetic ideal—the realistic, vulnerable, even sometimes offputting qualities of bodies one encounters in everyday experience. At Gina Gibney's, all the performers cut nice figures, although some were more . . .intensively curated than others.

Dancer and choreographer Jon Kinzel, the formal curator of this program, explained his choices of Stuart Shugg and Anna Azrieli in a program note:

“This commission represented a valuable opportunity for [Shugg] to collaborate with a documentary filmmaker. Having known Stuart for many years, I felt his desire to step back from the stage by getting a chance to set work on other dancers would provide him with some critical distance and perspective. . . .I chose Anna because, after viewing several of her works, I noticed her state-of-working-something-out-in-the-realm-of-a-contemporary-dance-piece was complex, compelling while also ordinary (creating an odd and at times humorous tension), slightly gutsy, intellectual, emotional, design-savvy, and always steadfast.”