IMPRESSIONS: John Kelly's “Underneath the Skin" at NYU Skirball

October 11, 2019

Mise-en-scène, direction, choreography, video, costume, and set design: John Kelly

Original texts: Samuel Steward

With Hucklefaery (né Ken Mechler); Chris Harder; Alvaro Gonzalez Dupuy/Estadoflotante; and Lola Pashalinski

Music: Russ Columbo, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Ludwig van Beethoven, Jean Lenoir (sung by Lucienne Boyer), Judee Sill, Iron Butterfly, Bessie Smith, Lucille Bogan, Ma Rainey, George Hannah, Peg Leg Howell, Kokomo Arnold, Gene Malin, Gladys Bentley

Are they really so lucky, the lads who die young?

At one point in his fabulous new production, Underneath the Skin, performance artist John Kelly recalls poet A.E. Housman’s valediction addressed to young men struck down in their prime. Champions never to be out-run, their beauty never to fade, they “carry back bright to the coiner the mintage of man.”

This perspective is definitely a queer one; and Underneath the Skin, which made its debut on Friday at New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, is a wonderfully queer show. Yet this selfsame production proves there is more than one way of looking queerly at things — don’t worry, you won’t lose your membership card — and that, in fact, an early grave has been over-rated.

Kelly’s subject is an unapologetically gay man named Samuel Morris Steward (1909-1993), who did not seek out doom, but survived to an age when he was thoroughly ripe and had known epic adventures. In a time when people attracted to others of their own sex were forced to conceal themselves, or suffer the consequences, Steward not only lived bravely, but also took notes. Thanks to him, we can reclaim part of our history that would otherwise have been lost.

He was not an idle dreamer. No, Steward was a man of appetite, and of action. Yet he was also a thinker, always questioning his condition and demanding answers from a hostile world. When we meet him, in Underneath the Skin, he is in his twenties and asking himself, for the first time, how to reconcile his desire for love with a conventional career. The career wins temporarily. Steward becomes an English professor. But love will not be denied.

Steward is also an autograph hunter, and an especially successful one. He got much more than a signed photograph from Rudolph Valentino, erstwhile idol of the silent screen. Valentino emerged from his bath to greet the young man in his hotel room, whipping off his towel and leaving Steward with a souvenir of a personal nature that he kept in a reliquary. Steward also longed to kiss the lips that Oscar Wilde had kissed; and sought out Lord Alfred Douglas. Though “Bosie” was by then in his 60s, and no Valentino, Kelly shows us Steward daintily picking a hair from his tongue as he leaves the encounter with Douglas, mission accomplished.

Despite this reverence for literature, which also led him to seduce Thornton Wilder and to maintain a correspondence with Gertrude Stein, Steward felt confined in academia. He launched a second career, shaking off alcoholism just in time and becoming the celebrated tattoo artist Philip Sparrow. Tattooing placed him in intimate contact with men whom he loved by the hundreds. His detailed records of these encounters in a “stud file” made him a valued colleague of the pioneering sex researcher Alfred Kinsey. Steward also made erotic drawings; and went on to write a series of ejaculatory novels under the “nom de porno” Phil Andros.

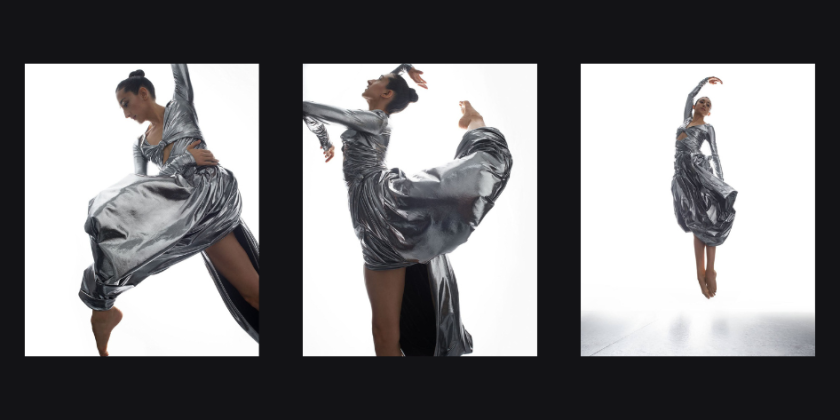

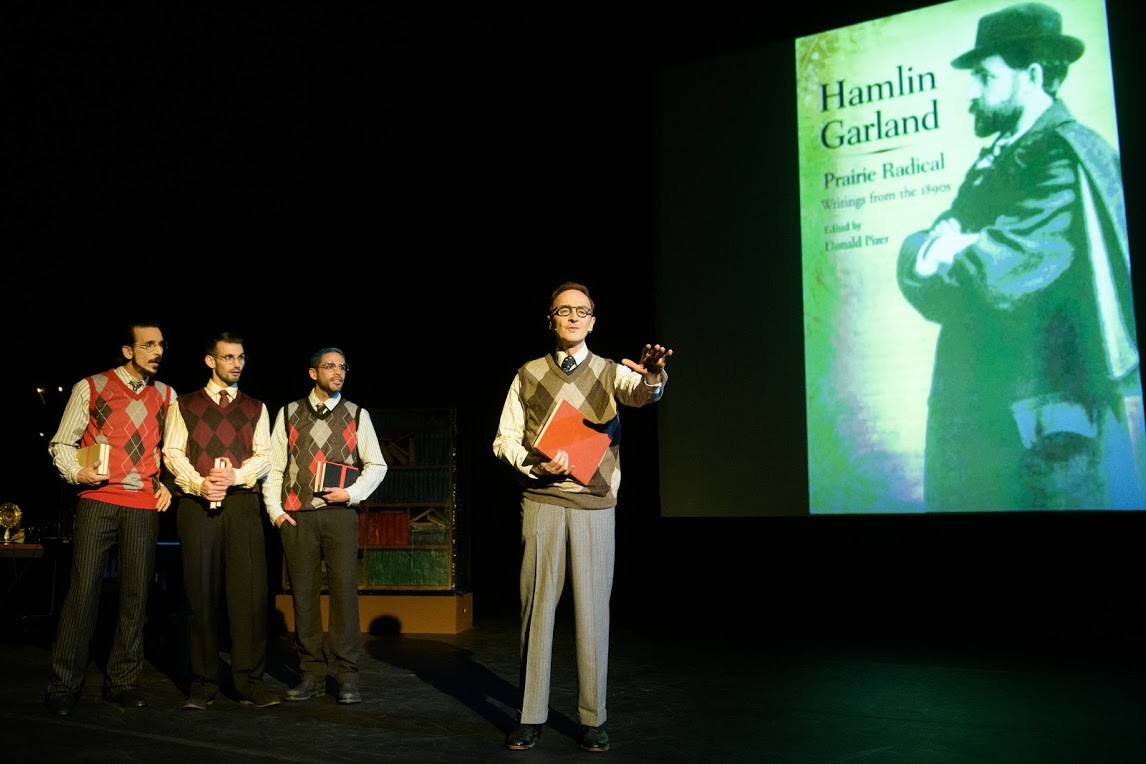

Perhaps only Kelly, owner of countless theatrical aliases, could do justice to these experiences. In Underneath the Skin, Kelly acts, dances, and sings, making himself a triple threat to homophobes everywhere. Assisting him are three young men who do not mind dressing up to resemble historical figures, or undressing to simulate an orgy. Lola Pashalinkski does a star turn as the gravelly, on-screen avatar of Gertrude Stein. Yet it is Kelly himself, wildly impassioned, who carries the show. He lectures; he fellates; he carves designs into skin. In the dance sequence, he bucks and prances with the energy of a man half his age. At the end of the evening, when Steward is dying and he should be, too, Kelly finds the breath to sing a wistful lullaby, rocking us all into dreamland and a sweet farewell.

As the show’s director, designer and principal videographer, Kelly also supplies an extraordinary collection of historic images to accompany and frame the action. Erect penises nod joyfully, or plunge into man-holes. Ballet dancers bourrée on pointes. Most of all, same-sex couples of all kinds embrace, hold hands, and kiss in woodlands, on piers, in kitchens, and anywhere else they find themselves safe.

These couples display a joy one rarely sees in photographs of heterosexual couples, I think, with the possible exception of wedding photos. Even posed stiffly in a photographer’s studio, the queer folk have a glow in their eyes; and one senses the relief they feel in one another’s presence, and their astonishment experiencing a love they feared could never be theirs. In stolen moments, they have allowed themselves to be stubbornly, and unreasonably happy.

In contrast to these pictures, and most horribly, Kelly also shows us images of medieval people burned at the stake; of sadistic 20th-century medical procedures to “cure” homosexuality; and mug shots from American prisons and from Auschwitz.

Steward lived his life between these two poles, with the promise of ecstasy on one hand and disgrace and torture on the other. He was often puzzled, and sometimes dazzled, but he took life as it came, and his creativity flourished. It seems never to have occurred to him to die young.