The Dance Enthusiast Asks Mina Nishimura About Making Faces And Dances

In her highly expressive work “Princess Cabbage/Celery of Everything” (Premiere)

When: Thu-Sat, October 29-31 @ 8pm

Where: Danspace Project, 131 East 10th Street, New York, NY 10003

Tickets: $20 general, $15 Danspace members

About:

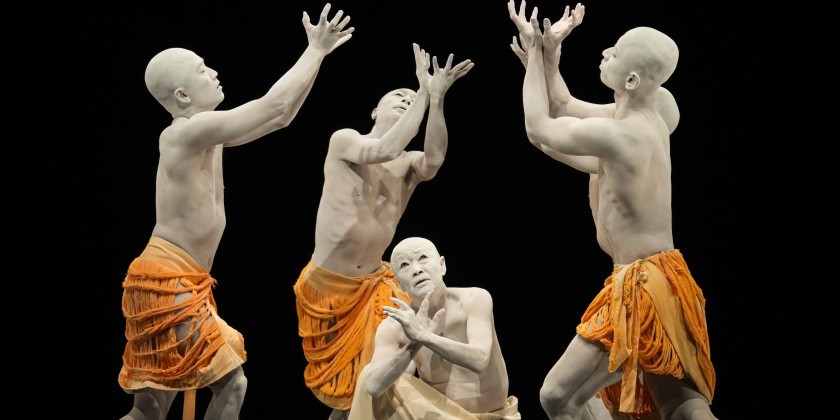

Tokyo-born choreographer and performer Mina Nishimura presents two new works that emerged from research into Butoh scores. The biographical novel, Sickened Madonna, by Butoh originator Tatsumi Hijikata, which often evokes images of the grotesque body, serves as inspiration for a solo called Princess Cabbage, which was commissioned by Mount Tremper Arts in 2014. Nishimura playfully channels fantastical and bizarre images from Hijikata’s book into movements, vocals, and facial expressions. Hundreds of drawings accumulated during Nishimura’s creation process will be exhibited as a stage set.

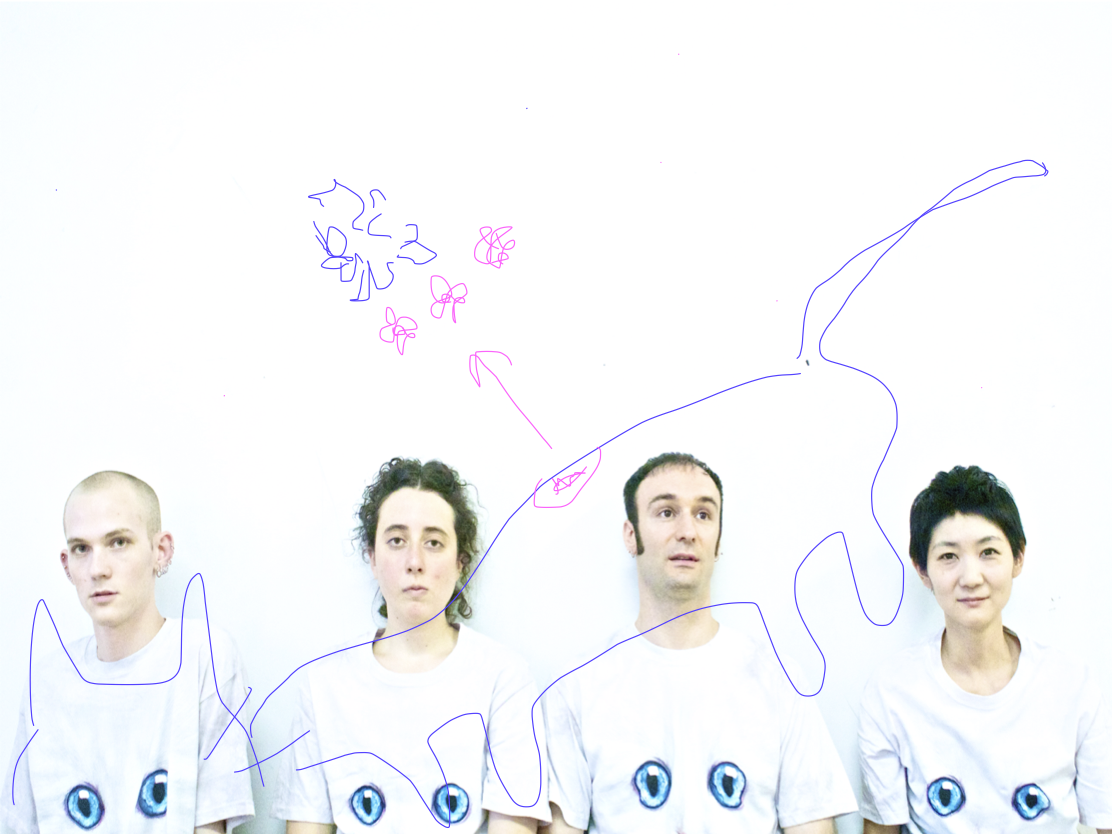

A new quartet, Celery of Everything, performed by Nishimura with Sarah Lifson, Connor Voss and Christopher Williams, explores the bidirectional relationship between internal landscapes and external forms through the use of images from butoh scores, abstract shapes, and irregular rhythm patterns. Multi-layered streams of movement and text flow in and out from individual internal realms, creating a colorful universe of imagery.

Sammi Lim for The Dance Enthusiast: I was surprised to learn that Butoh became a stronger part of your repertory only after moving from Japan to the US. Do share some memories about your first ventures into the Japanese contemporary dance form.

Mina Nishimura: I was already familiar with butoh before moving to NY through my boyfriend (now husband) Kota Yamazaki, who is a butoh-influenced artist. However, I had never practiced butoh until 2002 when Kota decided to do a butoh performance with me in one of underground theaters in Tokyo. One of my most striking memories about the performance is when Kota broke in during my quiet solo, and started yelling at someone (maybe a technical staff who had misoperated the sound system). That kind of provocative act is common during butoh performances, especially in the old times. I assume he did it to draw out my raw energy and reactions, but I was too young and ignorant to understand it! I cried and laughed at the same time during my solo on stage. But it was the moment when I discovered true depth within my body.

Although I’ve been practicing butoh since then (through workshops led by other butoh artists and by listening to stories told by butoh practitioners), it is true that these practices became more alive in my body after I was immersed in western dance forms and ideologies in New York such as the Cunningham technique, release technique and post-modern dance. I believe this was a natural and instinctive progression my body wanted to follow.

TDE: Sickened Primadonna by Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the forefathers of Butoh, was the catalyst for Princess Cabbage. What were your first impressions of the book? Were you taken aback by the rawness of the imagery?

MN: Yes, Princess Cabbage was formed by thousands of imageries from Sickened Primadonna. My first impression was… I didn’t know how to read the language. I could not hold onto it. But as soon as I realized that the book was meant to be read through your body and not with your brain, I became more comfortable with the raw and grotesque imageries! These imageries speak to and affect your body because of their very rawness.

TDE: You read the book in its original Japanese text, I presume? Did this pose a problem when translating certain phrases into English and conveying the imagery to non-Japanese-speaking dancers?

MN: Yes, I read the book in Japanese! As most of the imageries are specific to Japanese culture, it was very difficult to translate it into English. I also think that the Japanese language is well-designed to express subtle nuances and vague feelings, while English seems more useful for clear and precise descriptions. For example, “buya-buya” doesn’t mean anything, but Japanese people will get a sort of feeling; it is very challenging to transmit such vague nuances! But I believe that translated texts are still useful for creating unfamiliar states and modes in a body. And we don’t need to worry about understanding or portraying these images. Words come alive in our bodies only when we successfully hold on to the nuances of the words as opposed to getting stuck in the literality of them.

TDE: I personally find it tough to avoid being dismally literal when linking words, imagery, movements and ideas. How do you know when you’ve achieved harmony between these components?

MN: I have a desire to explore ideas from different angles. As I probe each element, they start talking to each other and a specific space starts emerging out of the conversation between the different elements. So it's not that one element serves another element. I’m aware that words have the power to instantly navigate audiences to a specific direction or situation. Visual images create a specific environment and bring another life to space. And to think how movements swim through, penetrate, expand or crush these loose frames and imageries set by languages and visual images is the most rewarding part in the creation process.

TDE: Princess Cabbage has gained quite a reputation for its speedy change of alarming facial expressions. Do your face muscles hurt after a performance? Sometimes my cheeks ache after a game of charades.

MN: Hahaha... That’s funny question! Yes, my face sometimes twitches. But I regularly conduct a practice called “starfish face" where I imagine a thousand feelers covering my entire face, with each one receiving different information. Using this practice, I try to articulate and activate every little muscle in my face.

TDE: I see you’re also a visual artist! I’ve seen some of your sketches and I love them. (Nishimura’s drawings are highly personal in the sense that their abstraction makes perfect sense to her artistic reasoning; her sketches serve as diagrams for planning out audience seating, performer positions, gestures and expressions, et cetera). I read that these works of art will double as a stage backdrop; how will this inform the performance?

MN: Yes! The drawings accumulated during my creation process will be exhibited as a stage backdrop, and will act as chorus silhouettes for my solo. There will be a gallery viewing between the two performances during which time the audience is invited to look at them. The act of creating these drawings, which were created in response to Hijikata’s Sickened Primadonna, became an important practice. The sketches are a bridge between the imageries in the book and my own body.