DAY IN THE LIFE OF DANCE: David Parker of The Bang Group on Scrambling Musical Theatre, Male Intimacy, and His Company as Family

THE BANG GROUP is a contemporary theatrical dance troupe that is devoted to choreographer David Parker’s fascination with the rhythmic potential of the dancing body. At the center of his work is an abiding love of rhythmic form and the intensity of communication it allows between audiences and performers.

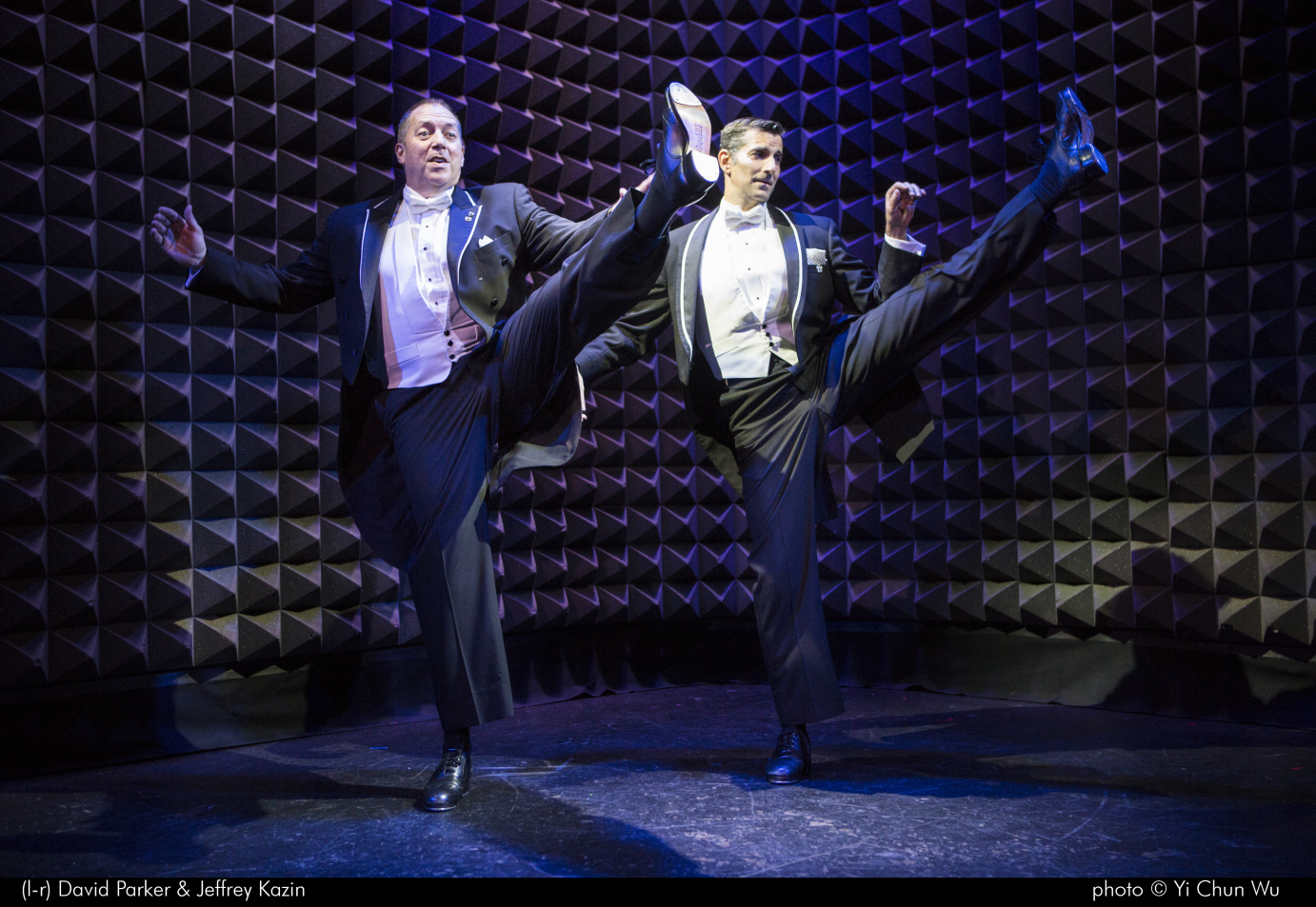

DAVID PARKER is a 2013 Guggenheim Fellow in choreography and, together with Jeffrey Kazin, leads The Bang Group which they founded together in 1995. Parker grew up in Lynnfield, MA, and began studying tap and ballet in Boston as a teenager where he launched his career by tap-dancing on city sidewalks with Maureen Cosgrove in 1978. Parker later attended Bard College where he studied ballet, modern, and post-modern dance. It was there where he began to build a polyglot form that used all he knew. His early work, Bang and Suck, was a finalist at the 4th International Competition for Choreographers of Contemporary Dance in the Netherlands in 1994, following which The Bang Group was launched.

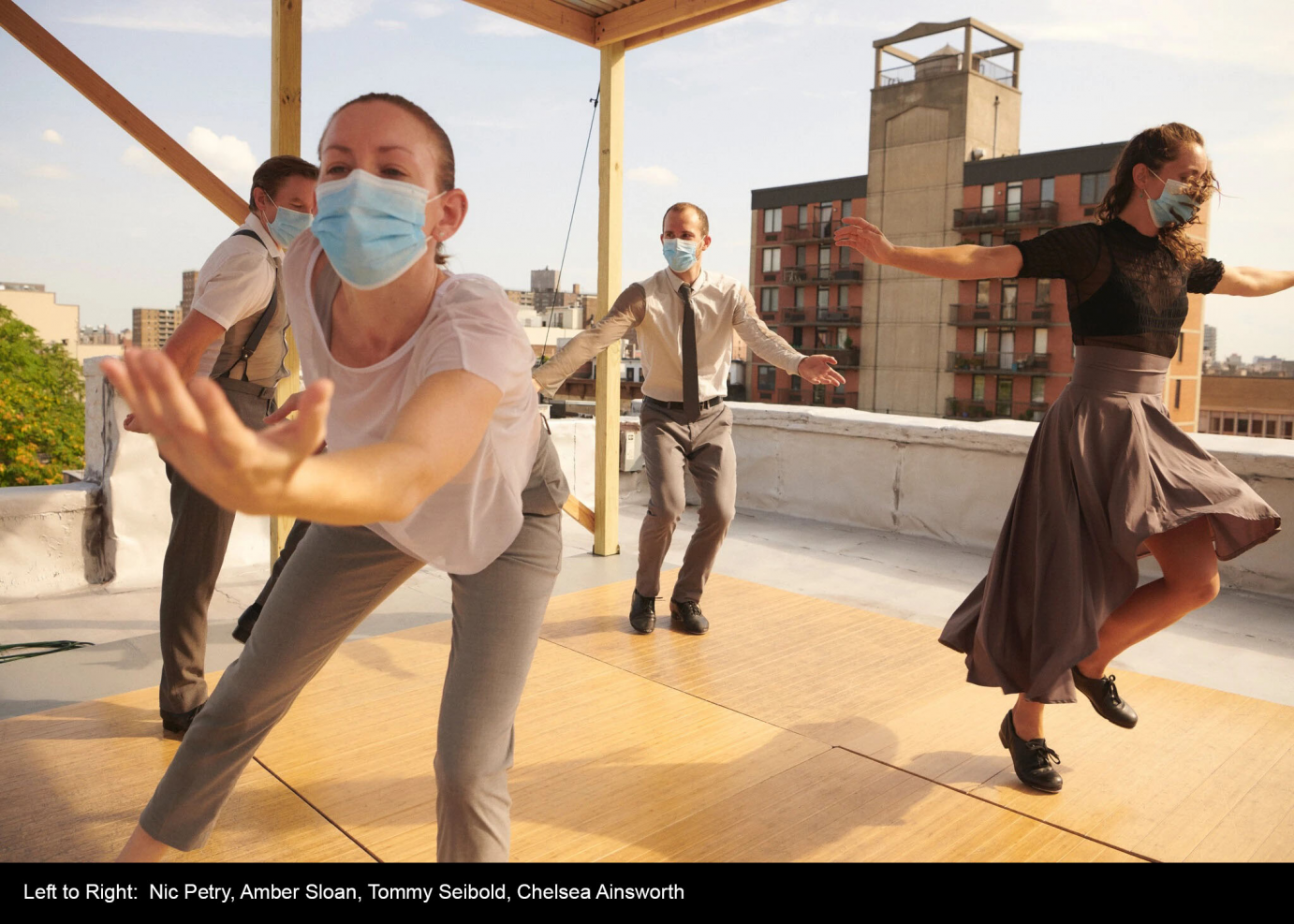

Known for spirited, irreverent, and brainiac dance revolving around a rhythmic core, The Bang Group, launched in 1990, incorporated in 1995, by David Parker and Jeffrey Kazin, continues to delight and amaze. As seen in their recent performance at Arts on Site, flurries of percussive sounds, a hallmark of TBG, often packaged in short but sweet offerings, attest to choreographer Parker’s ability to pack a punch in a limited time. On this program, TBG presented dances with titles such as Bach and Boogie Woogie, We’re Not Married, and Jeff’s Soft Shoe — the titles hint at content.

Parker’s aforementioned ability to pack a punch in a limited time is redolent of the choreographers of the early and mid 20th century admired by the choreographer; they utilized few movements to express multitudes. Parker’s “dances develop with content and craft intertwined; inseparable, and thus feel inevitable despite the turns and twists,” notes Nic Petry, who danced with the company from 2002-2021. There is frisson between the insistent tapped and sounded movement scores — the ‘tap’ designation is used loosely here. The poignancy of the movement leads, often to an inevitable yet unexpected place of tender realization “without aiming,” observes Parker. “Set the right elements on a collision course and it will get to the emotional.”

Parker and Kazin discovered early in their collaboration that they each have an unabashed love for Hollywood musicals and musical theater, movie scores, the Great American Songbook, and the routines of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. This delight in the music of the glamor years juxtaposed with an original movement style elicits an illusory and comforting sense of time and place. “My own dance-based version of musical theater but scrambled,” illuminates Parker.

(L-R) Tommy Seibold, Jeffrey Kazin and Dylan Baker in "Turing Tests".

Parker’s take on tap departs from stylized tap dance. In addition to their own form of tapping, the company members dance barefoot or don pointe shoes to create sound. Percussive scores often utilize every part of the body. Without a thought of movement hierarchy and on a continuum with other forms, the company’s movement style is a blend of modern, ballet, tap, and other genres. Rhythm is the organizing principle.

Caleb Teicher, the tap choreographer wunderkind, represents the next generation to carry on Parker’s craft. “These ideas seem to exist outside of a lot of idiomatic forces in most tap dance and body percussion practice, but they are absolutely in dialogue (and excellently so) with those traditions and communities.”

Additional musical choices include compositions by iconic classical composers to experimental contemporary composers and commissioned scores. Composer and violinist Pauline Kim Harris, who joins Parker for Sparkle (2020), developed a 12-tone scale, based on a Korean haiku called a sijo, that expresses joy. “One’s experience is enlightened by knowing the counterpart. In this case, the opposite of joy: sorrow, misery, anguish, grief, sadness, despair. I chose to start with the softer-sounding pointe shoes and end with the more resonant tap shoes. Dynamic and tension are built into the score by the adding and subtracting of “notes” — in this case, shoes. Each addition creates more complexity and borders on chaos and dismantling.”

Parker speaks of the tension in the movement he develops: “I don’t like things that feel organic. I don’t like things that feel inevitable nor things coming together efficiently and easily. I like the fight between elements like my feet and my upper body — rhythms that don’t go together. I am galvanized when things feel nearly impossible.”

Working out the impossible in the movement often results in struggle in the studio. Says dancer and muse, Kazin, “David’s sense of what works, or even worse, what can’t or won’t work, is frustratingly precise. As David’s brain is furiously attempting to find the best movement, I am furiously attempting to inhabit that movement.” Adds longtime TBG member and choreographer Amber Sloan, who joined the company in 2001, “There is rarely a time when I'm not challenged in rehearsal. Not only because of the range of movement we are asked to perform — modern in a percussive rhythm, tap dance on pointe shoes, intricate partnering, unconventional tap dance — but also because of the complex choreographic puzzles presented in the process. We play in that process with him”.

Says Parker of his own mentor, Aileen Passloff, who emphasized intuition. “Her voice was always in my head asking me to feel things simply and fully and to allow for silence, stillness, quiet. She used to say that doing nothing is not doing nothing because time is passing (which is something) and the audience needs that space to meet the work.”

The crux of Parker’s oeuvre is a series of duets created with Kazin that explore male intimacy (Parker and Kazin each maintain long-term domestic partnerships). Parker speaks of his work as gay and queer: “Queer in the sense of looking at love from an angle, looking at cherished traditions as something to be pulled apart and remade from a somewhat outsider's vantage point. I place intimate, romantic relationships between men at the center of my duet work. I have focused on intimacy between men as I have understood and lived it myself. It reflects my life history.” Works for the full company feature polyamorous, pansexual, and gender-fluid relationships.

It is rare that a group of dancers, the original core group of Parker, Kazin, Sloan, and Petry, dance together for nearly 20 years. With that dedication, much is accomplished. In 2019, dancers Dylan Baker, Tommy Siebold, and Louise Benkelman became full company members. In addition, Daniel Morimoto and Chelsea Ainsworth work with the company.

The dancers remark on the trust and loyalty Parker affords each, and as a result, they develop trust in and loyalty to each other and to Parker’s choreographic process. A witty mentor and a highly respected teacher, Parker is known for his generosity and support of each dancer’s growth. As well as his meritocratic artistic inclusiveness that guides the company’s ethos. Company members describe TBG as a family who eats together, sees one another socially, and often vacations together. According to Kazin, “The work is built on and sustained by a level of intimacy. We’re devoted to each other.”

Sloan speaks of visiting Parker’s family home when performing in Boston and noted that Robert B. Parker, the acclaimed novelist and David’s father, wrote every day from 9am until 5pm. This example of discipline and dedication informs TBG’s bedrock work ethic; the company works from Monday to Friday year-round — with vacations, of course. It is a reason why the dances reach nervy heights of continually evolving complexity, inventiveness, and affecting emotional largesse. Parker has been described as projecting Yankee aloofness, yet those who know him describe him as extremely funny and approachable. Humor is reflected in the dances. TBG’s lighting designer, Kathy Kaufmann, who met Parker in 1982, pays special attention to TBG’s humorous facial expressions: “Just a raised eyebrow can convey so much and add to the success of the piece.”

Parker recently underwent a knee replacement that entailed a long recovery. During recovery, Parker entered the studio alone — an unusual practice for him — to discover what he could do without resorting to old proclivities. He challenged himself to use his body as an object that tested his capabilities. These experiments, which include jocoseness, whimsy, and continued complexity, guide his latest dances and fold into and inform current and future works that promise to continue to enrich and further the field.