IMPRESSIONS: Big Dance Theater in "The March" at the Perelman Performing Arts Center

Choreography by Donna Uchizono, Tendayi Kuumba and Annie-B Parson

Big small feat

Choreographer: Donna Uchizono | Associate choreographer: Levi Gonzalez

Composer: okkyung lee

Costume designer: Naomi

Stage manager: Ilana Khanin | Company manager: Lilach Orenstein | Executive director/Producer: Sara Pereira da Silva | Production manager: Daria Walcott

NYSea

Choreographer: Tendayi Kuumba

Costume Designer & Associate Artist: Greg Purnell

With: Mewu Ama Me’et Gora, Brooke Ashley, Stacy Dawson Stearns, Natalie Greene, Meg Harper, Kashia Kancey, Joanna Kotze, Jennifer Nugent, Devin Oshiro, Pamela Pietro, Kendra Portier, Jin Ju Song-Begin, Chanel Stone, Hsiao-Jou Tang, Paz Tanjuaquio, Isabel Umali, devika v. wickremesinghe

Sound design: ÜflyMothership

The Oath

Choreographer: Annie-B Parson | Associate choreographer: Elizabeth DeMent

Lighting designer: Jeanette Yew | Sound system designer: Ryan Gamblin | Sound designer: Tei Blow

Costume designer: Sam McElrath

Venue: Perelman Performing Arts Center

Date: December 13, 2023

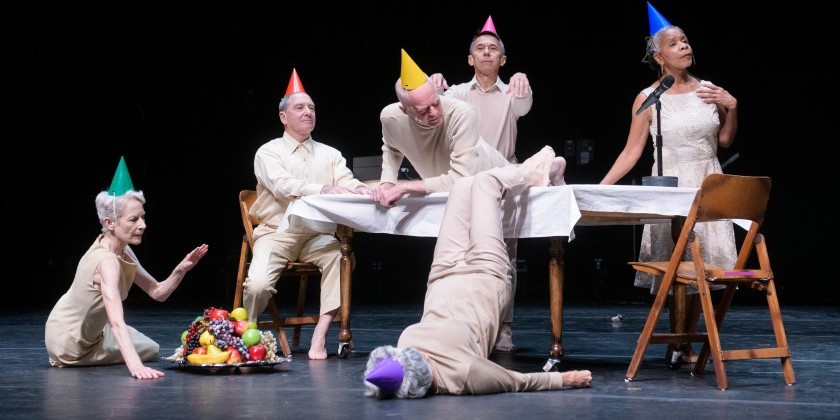

Marching in lockstep may have helped to build civilization, but is not an activity typically associated with post-modern dance. Our downtown choreographers are free-wheeling, independent types, whose response to military drill is likely to resemble The March, a flaky and rambunctious creation in three parts, which received its premiere on December 13. Big Dance Theater performed this piece, which the Perelman Performing Arts Center commissioned for the Zuccotti Theater, a quirky space in which viewers in steep balconies gaze down at the circular stage. Here, in The March, choreographers Donna Uchizono, Tendayi Kuumba, and Annie-B Parson consider the implications of moving in unison as a kind of thought experiment.

These dances for 17 women of varying ages suggest games in a children’s playground more than the Black Watch on parade; and their whimsy may seem at odds with the somber atmosphere of the 9/11 Memorial across the street. Yet the dances were made for this location. In their meandering, oblique way, they ask us to remember the last time our nation felt truly united, and to what end. Clearly, we are not united now — why not? And what should our response be, the next time we are asked (or more likely told) to join ranks?

Protesters march for justice. Soldiers march off to war; and, Oh Lord, we all want to be in that number, “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Uchizono is vague about the circumstances, however, in the opening piece, Big small feat. Her dancers cluster together demurely at the center of the round, white stage, kneading the floor with bare feet. Then they rush to the edges stomping. As the piece progresses, some moves are clearly defined — ironic body-builder poses, and small ronds de jambe. Other movements seem too finicky and personal to be imitated. The dancers work their mouths seeking to form words, and their bodies shift uncomfortably without taking a definite position. Joining in lines, they touch without grasping. The women seem so delicate in their crinkled, aqua dresses, and their movements so uncertain that when the stage darkens briefly, one fears the arrival of a predator (Morlocks!). Yet, near the end, they rush forward in a hooting chorus, revealing an unexpected reserve of strength. Unity is there, when they need it.

"The March" in NYSea by Tendayi Kuumba. Photo by Whitney Browne

Kuumba’s NYSea goes beyond unison movement to suggest the absorption of the individual in the natural world. At the outset, Kashia Kancey finds herself marooned in a circle of light. Desperately she begins to write, scribbling on the floor as an ocean is projected around her turning her body into a lonely island in the sea. There’s no need to panic, however, for Nature itself, in the person of Kuumba, seems concerned for her. “I’ve been wondering how you’re sleeping,” Kuumba croons from the sidelines, before calmly advising Kancey to “take your time.” More watery images are projected — spreading circles, and showers, and an inky stain that dissolves — and dancers engulf Kancey like a passing storm. Yet she seems to find peace in this maelstrom, as Kuumba reminds her she has water in her soul. Alone again, Kancey opens her hand in a gesture of release.

If the dancing in these first works seems loosely arranged and ragged at times, patterns become simpler and the cast more obviously disciplined in The Oath, this evening’s pièce de résistance. Annie-B Parson is the unseen ringmaster cracking her whip offstage; and here, at last, we see the dancers arranged in long, wheeling lines of the type that are the pride of national folk-dance companies. The goal of such designs is not simply unity but uniformity, as the individual submits with unquestioning obedience to the dictates of “tradition” and the national will (and whoever controls it), achieving perfect anonymity in a display of visual rhythms trailing to infinity. Is it comforting or stifling to lose oneself in a grand design that cultural signifiers like cowboy hats or flowered chaplets may lead us to identify with home? Sam McElrath’s filmy white costumes with backpacks suggest a cross between First Communion and basic training; and Parson clearly has religion on her mind, as her dancers perform ritual gestures, elaborately blessing themselves or trying to ward off evil. Naturally, the obsession with purity leads to conflict and abuse. Early in the piece, the dancers step rudely on each other’s backpacks. Later, two lines face off in opposition; and Parson disarms the situation, hilariously, by giving her rival teams (one lying prone, the other standing) a dialog more like an intimate discussion than a war. The threat of violence is never far off, however, as the need for ritual efficacy can make the slightest misstep fatal. At any moment, The Oath could turn into The Rite of Spring.

It's too bad, really, that the dancers must perform The Oath indoors, rather than on Memorial Plaza, where crowds of the faithful wearing 9/11 merchandise could ogle it in wonder — but The Oath is more subversive than the annual Table of Silence Project at Lincoln Center, and it might confuse people. So, The Oath remains locked up inside the Perelman Center’s mysterious depths, like the proverbial riddle inside an enigma. Someday, perhaps, we will get 9/11 Truth. In the meantime, we have Big Dance Theater.