Opening Night of Danspace Project 2018 DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES AND DOWNTOWN DANCE curated by Reggie Wilson

Walking with Resilient Spirits: The Struggle For Space, Freedom to Move, and Search for Justice

A Walking Tour of the East Village with Cynthia Copeland

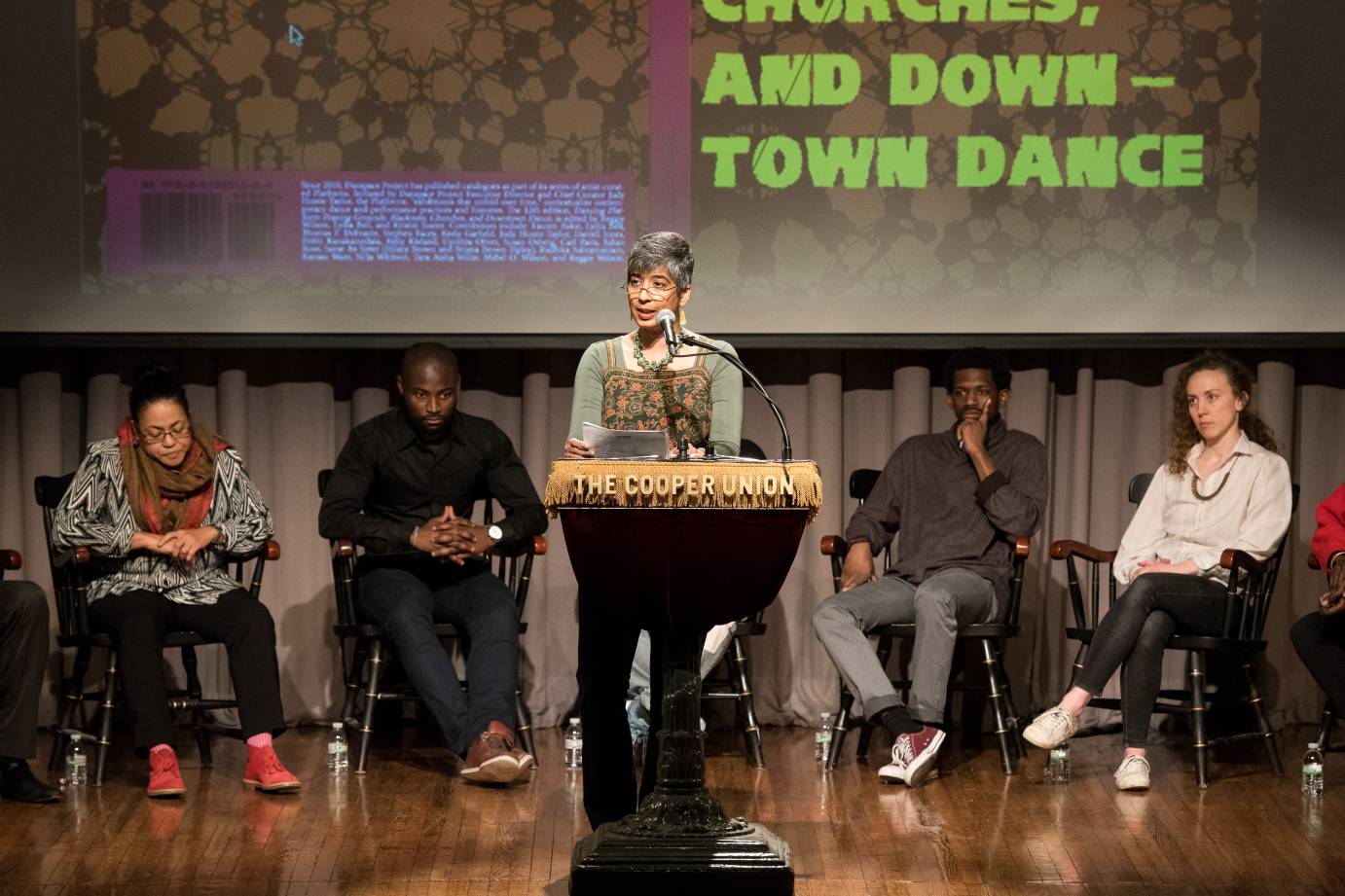

Opening Event at The Great Hall of The Cooper Union

Dance Space Project’s Platform runs February 28 - March 24, 2018 , click here for more info and tickets.

Radhika Subramaniam, a contributor to Danspace Project’s gorgeous guidebook, the companion to its latest platform of talks, walks, and performance, describes the urban experience as short on view. “Once you commit to urbanity, your vision fades,” she reads aloud while standing in the Great Hall of Cooper Union. “Cities teach you about movement.”

Subramaniam can’t recall her first visual memory of New York City, but what is stamped on her psyche is the electricity of her foot hitting pavement.

While hitting the concrete for a tour of the East Village (one of four walking tours in this platform series), historian Cynthia Copeland asks how we connect to New York City.

Some of us were born here or have raised children that bind us to this place; some of us are transplants; some live between this city and another. Most of us could live nowhere else.

But do we know where we are?

Starting on the portico of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, we are encouraged to notice what is in front of us, and what isn’t. The surrounding land used to be a farm belonging to Peter Stuyvesant; his bust sternly glares at us as we enter the church’s courtyard. Prior to St. Mark’s Church’s existence, this is where the chapel for Stuyvesant and his family stood. Before Stuyvesant, the land belonged to the Lenape people. Imagine streams, a lush landscape with berry-filled trees and beavers running about.

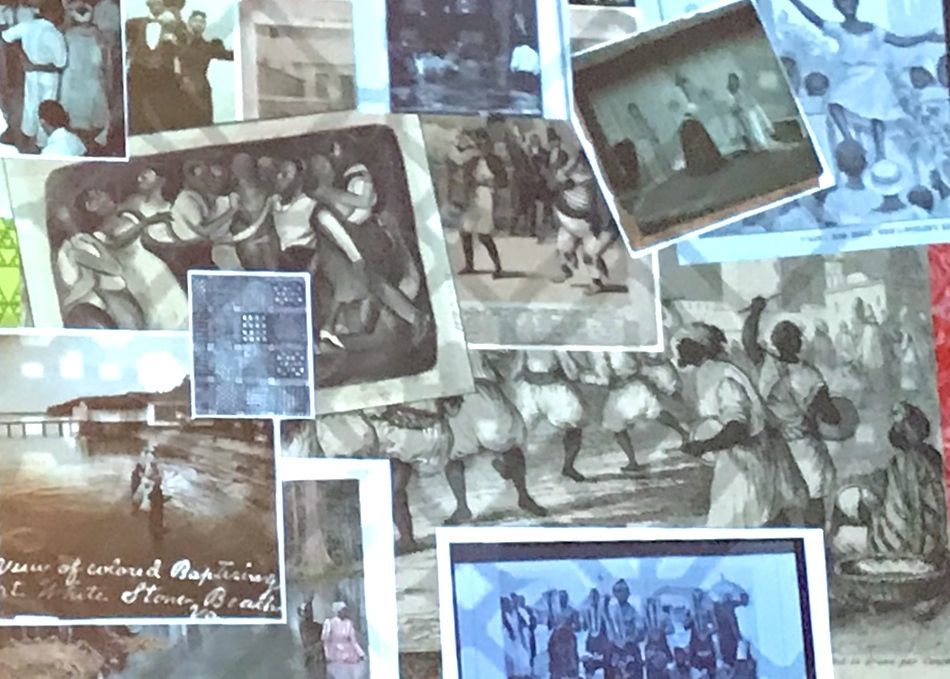

Enslaved Africans, by way of the West Indies, helped farm an estate that extended north, from Houston to 21st Street, and east, from Third Avenue to Avenue C. As we stop and stroll the downtown, we encounter some of their stories — stories we could easily miss in the speed of daily city life, and if not walking with a historian. The common threads, no matter the time period, are a struggle for space, the freedom to move, the search for justice, and a resilient spirit.

During the Dutch occupation (mid-17th century), Black people demanded their own space in the church, to worship and to marry. For a quota of goods, they could have it. If no quota — then, no liberty.

Beneath our feet lies Mangle Minthorne (1737-1821), a distinguished New Yorker and pillar of St. Mark’s during British rule. Our guide reads a lengthy newspaper ad he placed, in which he vehemently complains that his “property,” a runaway slave, has been masquerading as a free man. Minthorne is hunting the man down, entreating the community to return his possession posthaste — there will be a reward. Peering at Minthorne’s cool, marble grave marker surrounded by the 21st -century, colorfully non-conformist, progressive East Village vibe, it’s hard to imagine these cruel attitudes were once status quo.

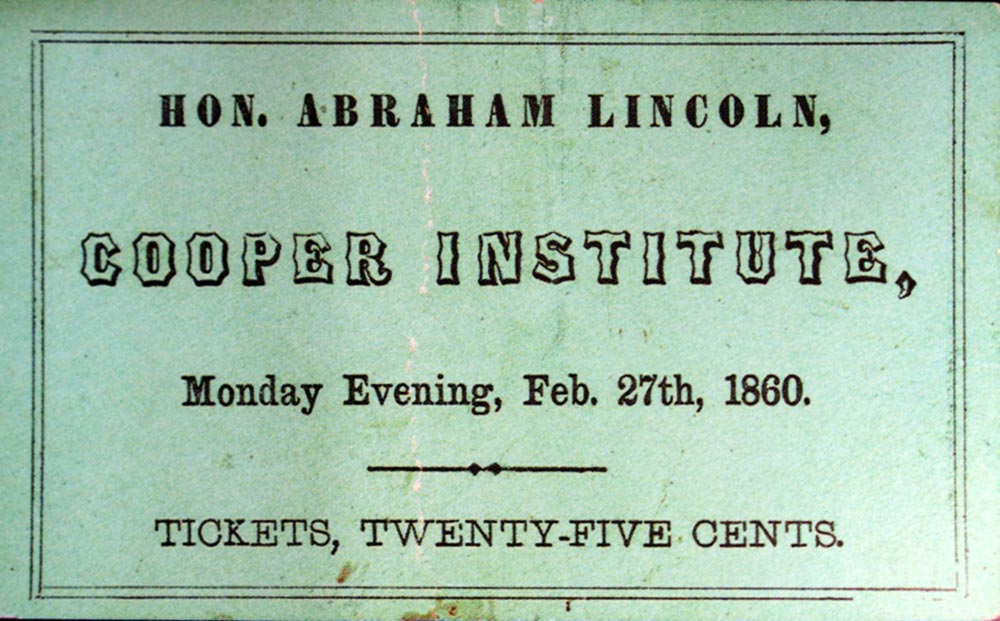

Just outside the Foundation Building of The Cooper Union, home of the Great Hall where Lincoln gave the anti-slavery speech that sealed his bid for the Presidency, we’re told about a young, free Black woman, called Elizabeth Jennings.

Image of Ticket to Lincoln’s Cooper Union Speech http://www.boweryalliance.org/did-you-know-this-about-the-bowery/

On a summer’s day in 1854, running late to play the organ at the First Colored Congregational Church (on Sixth Street near the Bowery), Jennings jumped on to an all-white railcar. Asked to get off, she refused and eventually was bodily evicted by police. Sore, injured, but unbroken, she wrote a letter describing the incident that caused a stir in her church and the Black community. It was reprinted both in Frederick Douglass’ paper, The North Star, and The New York Daily Tribune. Determined to be recognized and treated fairly, Jennings then sued Third Avenue Railroad and won. 100 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat and move to the back of the bus, Jennings fought for the freedom to move in her own space.

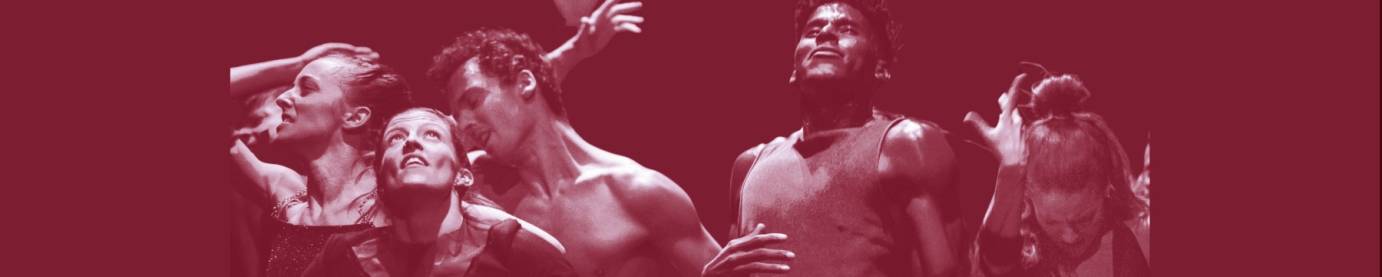

“We’re just going to walk for a while,” choreographer Reggie Wilson tells us from the podium in the Great Hall. We are inside the historic room now, and with the help of dancers from Wilson’s Fist and Heel Performance Group, we will reconstruct a Ring Shout, which is a circular rhythmic dance of praise. Wilson says it was the way Black people adapted their African practices to Christianity starting as early as the 1400s. The basic step is a shuffle and hitch, a stylized walk.

Wilson, an intrepid researcher of African and African-diasporic practices, uses his investigations of Black tradition to break new dance ground. The Ring Shout connects him to “what it means to be Black, and what it means to be African-American . . .” He uses the form as a tool “to help me move into wherever I go in the world and have something which is mine.” The mantra of the Ring Shout, Wilson says, “Rhythm is the thing.”

“Let’s start with just the rhythm, and as the speed starts to pick up a little bit, you’re gonna shuffle a little bit more . . ." says Wilson.

"A little bit faster. . .” he calls.

We respond, clapping and shuffling, hips slightly swaying.

“A little bit more, a little bit faster . . .”

Bodies radiate.

"A little bit faster. . ."

Clapping pulse and movement overtake the hall.

"A little bit faster. . . "

The Ring Shout lasts only a minute or two, but we’ve been activated. No longer a sedentary, silent audience, this community is ready to pound the pavement and experience new stories with open eyes.