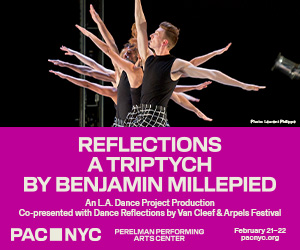

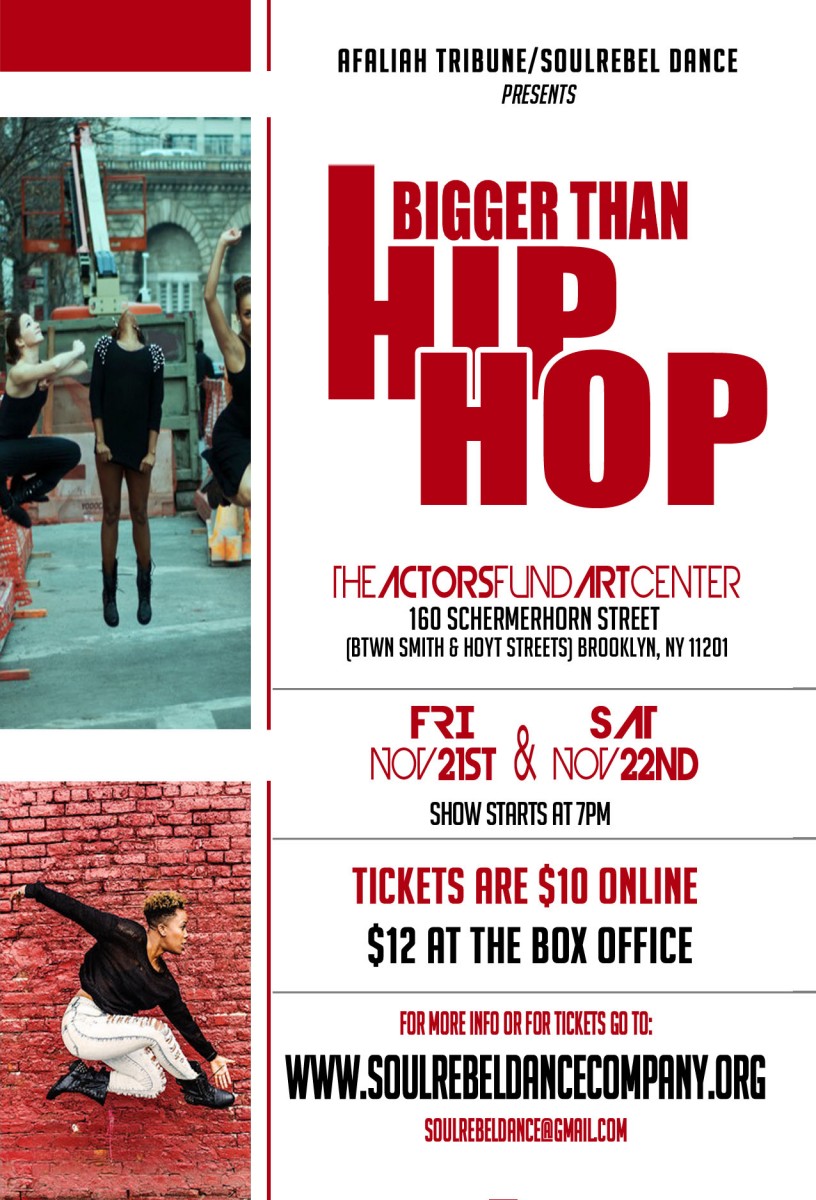

Impressions of Afaliah Tribune's "Bigger Than Hip Hop"

The Story is Bigger than Hip Hop

Afaliah Tribune/SoulRebel Dance

The Actors Fund Arts Center/The Schermerhorn

160 Schermerhorn Street

Brooklyn, NY

November 21 and 22, 2014

On November 24, 2014 at around 9:30pm EST, after a half-hour of what my grandmother would call “hemmin’n’hawin’,” St. Louis Prosecutor Bob Mucculloch announced the grand jury’s decision not to indict (now former) police officer Darren Wilson on criminal charges for killing Michael Brown, an unarmed teenage Black boy. Eight days later, a Staten Island grand jury chose not to indict officer Daniel Pantaleo for the death of an unarmed Black man, Eric Garner. Many of us repeatedly watched his upsetting arrest on video as he uttered, “I can’t breathe.” What does this have to do with dance, you may ask?

Historian Brenda Dixon Gottschild, author of The Black Dancing Body: From Coon to Cool, who speaks proudly of Alvin Ailey being a quintessential inspiration to George Balanchine in the 1970s, reminds us,“Dance is a measure of culture and a barometer of society.” In her newest work, choreographer Afaliah Tribune positions her audience in the center of this scale as we experience a storytelling rooted in culture, society, and most importantly history.

Just two days before the St. Louis grand jury decision, I witnessed Tribune’s Bigger Than Hip Hop at The Actors Fund Arts Center. Her work exposes the layers of American cultural history that have ushered in questionable police actions and jury decisions. In the days of protest that have followed, I continue to hear a signature loop of Tribune’s soundscape: “Post traumatic slave syndrome, post traumatic slave syndrome, post traumatic slave syndrome…” These are the words of Dr. Joy DeGruy who contextualizes her theory of post traumatic slave syndrome (P.T.S.S.) in a video clip at the beginning of the performance. Her lecture cites the lack of mental health treatment offered during the centuries of chattel slavery, followed by the continued trauma of lynching, Jim Crow, police brutality, and mass incarceration that followed emancipation. DeGruy’s clip is preceded by a Saturday Night Live video entitled “28 Reasons to Hug a Black Guy” (27 reasons of which are slavery).These videos lay the foundation for the fifty-minute emotional roller coaster of Bigger Than Hip Hop, a multi-dimensional choreographic work performed by seven multi-faceted Black women.

DeGruy’s research is one of many inspirations for this work. Tribune also cites Spike Lee’s film Do The Right Thing and Kanye West’s album Yeezus in her program notes. In the post-show conversation, she mentions her personal relationship to Hip-Hop music and culture along with her study of MK Asante’s It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation. Tribune shares that the music selection, which includes music by Kanye West, Ludacris, and Ice-T, is a testament to her belief in the storytelling power of “classic Hip-Hop” and homage to Hip-Hop as the language in which she speaks and creates. These historic and artistic elements come together to tell a complex story of the violence entrenched in American history and its effect on Black bodies.

“Blood on The Leaves,” one of the most spellbinding sections of Bigger Than Hip Hop, is set to Kanye West’s song of the same title. The dancers, facing the audience, sit and react as we are left to imagine what they are responding to. There is a generous use of the “side eye,” a sideways glance coupled with lips curled into a question that is the epitome of Black girl shade, which we love to offer up in unsympathetic skepticism. The dancers periodically throw their hands up in the air, embodying the only response I’ve been taught for interactions with the police -- arms held above the head in an attempt to prove innocence. This movement, whether symbolizing surrender or being just plain fed up, has become a signature in the protests following the shooting of Michael Brown. Many people, from news anchors, to university professors, to the St. Louis Rams have used this gesture (that even has its own hashtag #HandsUpDontShoot) to condemn police brutality towards unarmed Black people. The magnificence of Tribune’s “Blood On The Leaves” lies in the use of such honest, simple actions. The unspoken language wails loud and clear its challenge to our perception of Black bodies.

Bigger Than Hip Hop was a painful pleasure. Tribune blends Hip Hop and contemporary dance with recognizable actions of our shared history. There are agonizing gestures where we watch dancers being examined on an auction block or getting arrested. There are ambiguous moments where the dancers embody sexual Jezebel stereotypes. There are also heartwarming sections of embrace and enjoyment.

I remember excitedly shouting “Get it girl!” like I too was at the party as the women, moving along to a Ludacris’ “Pick A Bale of Cotton” sample, free-styled: rolling their hips; snapping their fingers; lowdown booty shaking; dancing with "lite feet;" and elegantly voguing. When the sound suddenly shifted to the original 19th century folk song “Pick A Bale of Cotton” - a celebration of slavery - I was engulfed in desperation as I watched the dancers reach and crumble. My stomach turned as Tunu Thom, her bare back to the audience, struggled and writhed seemingly unable to move from her seated position. My blood boiled in disgust during “Hannah Montana” as Kendra Ross groped Ashley Chavonne, who with a forced smile tried to scoot away. All the while Matia Johnson sat next to Chavonne showing only the slightest bit of annoyance. The dancers held each other up and stripped each other of their humanity, forcing me to re-navigate my own traumatic memories and question how my daily living fits into this complex communal reality of breaking down and holding up.

In Bigger Than Hip Hop, we witness herstories in a visceral storytelling that felt familiar. I found myself in a constant call and response between performer and audience, an interchange that felt connected to the Akan tradition of Sankofa, which translates to “go back and fetch it” and has been taught to me as a way of looking to the past to move through the present. The performance conjured deep-seated memories of the legacy of Black women who have made social and political movement through art and beyond. Women like Katherine Dunham whose work Southland dramatized the lynching of a black man in the racist American South and could not be performed in this country. I recall the storytelling legacy of Urban Bush Women in works such as Batty Moves, Walking with Pearl, and HairStories that share tales of Black womanhood through the beautiful bodies of Black women. I even think of Synead Nichols and Umaara Iynaas Elliott, the young women of color who organized, or rather choreographed, the recent Millions March NYC . They too are dancers. Bigger Than Hip Hop sits strongly with this legacy.

I also recalled images from Black women's creations that I've seen just this year.The child’s play that quickly became violent reminded me of Sydnie L. Mosley’s CAKE, which premiered in November and explored respectability politics in the pathway from Black girlhood to womanhood. The history, memory, men, children joy, and fear embodied in Tribune’s movement brought me back to the experience of multidisciplinary artivist (arts activist) Ebony Noelle Golden’s multimedia performance piece twohundredthirtyfour twohundredthirtyfour twohundredthirtyfour, a work that, Golden writes,“troubles and challenges the pursuit, practice, and mythology of freedom in the time of now.” Similarly in “Amerikkka,” another section of Bigger Than Hip Hop, Tribune’s dancers stand in front of an American flag as the patriotic tune of “My Country Tis of Thee” plays. Kendra Ross dons the "fakest" of smiles as she places her middle finger over her heart. This challenge to the romanticized America also evoked memories of Ase Dance Theatre Collective’s choreographer Adia Tamar Whitaker, who interrogated Christian iconographies in Dear White Jesus, a prayer through song and movement that I performed this May. Art possesses the ability to turn a mirror to society, and Tribune, like her ancestors, mentors, and contemporaries, has no problem placing that mirror in the most uncomfortable places.

Thankfully, after Bigger Than Hip Hop ends, we were not left to process our experience alone. The post-show Q&A opened with dancer and family therapist LaToya Hall providing further clinical context for post traumatic slave syndrome and its effects on the families she serves. Tribune went on to share the difficulty of crafting this work which began in July 2013 in the wake of a not guilty verdict for George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin, another unarmed teenage Black boy. Tribune admitted that there were times she had to step away from the work for her own self-care, reminding me of my own recent mantra inspired by the words of the writer Audre Lorde, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare” (from the epilogue to Lorde’s A Burst of Light).

Since 2013, it may seem these injustices against Black bodies have become more frequent. In fact, it is social media that has made unjust acts undeniably present in our daily lives. The oft-cited report by Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, Operation Ghetto Storm: 2012 Annual Report on the Extrajudicial Killing of Black People, reveals that in 2012 a Black person was killed every 28 hours on average by a police officer, security guard, or self-appointed vigilante. As our discussion continued, Tribune reminded us of more names we have learned just this year such as John Crawford III and Akai Gurley. It is also imperative to remember that this fate not only befalls Black boys and men, and honor the lives of girls and women who have died such as Aiyanna Stanley Jones and Yvette Smith.

As Tribune suggests, the story is much bigger than Hip Hop. It is bigger than Ferguson, or Staten Island, or Florida, or Chicago, or any other place where an unarmed Black person lost a life because someone “felt threatened” by their presence. Until “My Country tis of Thee” addresses the trauma that is ingrained in its foundations, the “Blood on the Leaves” will remain. I can only hope Tribune and other artists continue to hold up the mirror so that we might see ourselves and continue to move towards change.

I am Black, not black. That is not a reference to my skin color, but an acknowledgement of the cultural legacy of displaced peoples of African descent. We are not all African. We are not all African-American. But we are all connected by a history of colonialism, genocide, and enslavement. Therefore, I refer to us all as Black.