IMPRESSIONS: New Dance Ireland: Choreographers of Nowness Presented by 92Y and Irish Arts Center

April 27, 2019

Choreographers: Darrah Carr, Seán Curran, Oona Doherty, Aoife McAtamney, Mary Nunan, Liv O’Donoghue, Liam Ó Scanláin, Dylan Quinn, John Scott, Mufutau Yusuf

Guest Curator: John Scott

Where do Irish traditional and contemporary dance meet in New York City? The answer is the spacious yet intimate Buttenwieser Hall in a partnership between 92Y and the Irish Arts Center. Guest curated by choreographer and writer John Scott, this program examines the ways in which Irish identity impacts dances choreographed by Irish and Irish-American artists. Eleven choreographers — three from the U.S, seven from Ireland, and one from Nigeria — represent a wide perspective of Irishness and varying influences on Irish dance, from the traditional to the new.

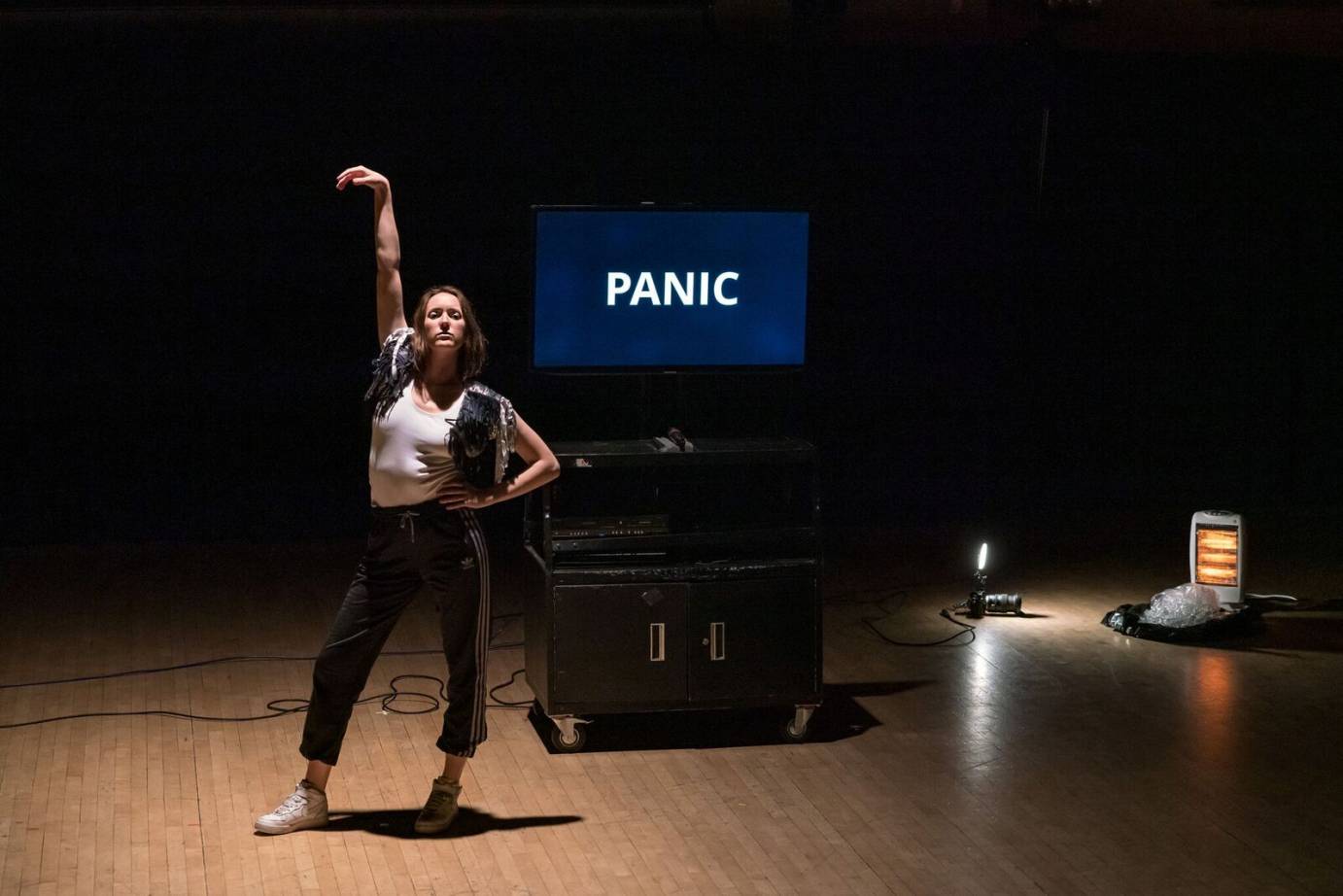

Dublin-based Liv O’Donoghue’s After (reworked), a somber live documentary infused with moments of humor, opens the show. Across continents and oceans, global warming ignites controversial feelings. Using live-stream film, spoken word, physical theater, and dance, we see the stages of an emotional breakdown, the denial and the acceptance. At the beginning, O’Donoghue sits on a chair and addresses the audience as her partner, José Miguel Jiménez, dumps a bag of ice in front of a space heater and projects its image onto a large TV screen. She speaks about caring “long enough to shake a fist on social media before going back to our dog videos” as the ice slowly melts before our eyes. In another moment, she tells us she meant to recycle, but pours herself a drink instead.

After takes us to the place following the ending, and the viewpoint O’Donoghue and Jiménez offer is one of almost relief. As we ride their emotional roller coaster, there is time to ponder on what part of the spectrum we fall: anxious, detached, in denial, angry? As the lights fade, O’Donoghue and Jimenez slip off chairs as the ice caps on the screen evaporate into a vast, roaring ocean. Eventually, we are left in darkness.

Most striking about the evening’s presentation is the rich emotional content delivered by fascinating movers, who perform solos except for O’Donoghue and Jimenez. Belfast-based Oona Doherty gives a thoughtful, raw, and beautifully articulated performance in Lazarus and the birds of Paradise. A captivating performer, Doherty is a helix of bound energy, a storm cloud about to break. In what she describes as a piece about “the male disadvantaged stereotype,” her body evolves through postures of aggression, anxiety, rage, and pain, like clouds drifting in and out of formation. Her persona — cocky, then vulnerable — fluctuates as her combative energy suddenly softens into a yielding hand or outstretched arm. Painful yet redemptive, Lazarus explores the struggle of Belfast’s streets.

Mufutau Yusuf unassumingly takes the stage before his fingers start flying, leading his body into circular movements during his work-in-progress, Pidgin. Punctuated by clapping and snapping rhythms, Yusuf delights in his ability to transition from tiny isolated movements to large jumps and torso undulations and back again, effortlessly, as if he is having a conversation with himself.

Aoife McAtamney is spellbinding in Softer Swells, a solo that unfolds like rapid shifts in memory. Her haunting Celtic voice sings a capella as her supple, searching movements convey a natural femininity. Out of nowhere, the dance increases in speed and urgency as McAtamney contorts herself in a birdlike and beautifully awkward flow. She drops and then spirals up from the floor as if boneless. Like smoke, she wafts and then fades away, into the curtain and off stage, leaving us with the impression of a subtle human experience that cannot be verbalized.

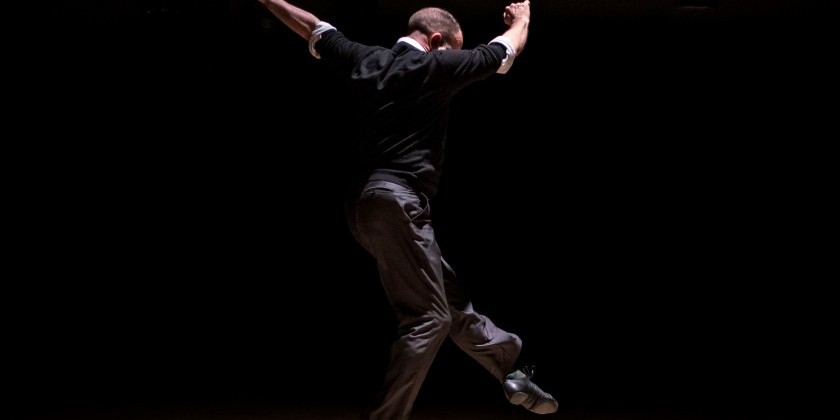

Seán Curran beguiles with his ability to execute complex rhythmic structures with little tension and effort. Quirky, surprising shifts of weight with an almost mime-like specificity of gesture characterize Esti Dal, set to the Hungarian folksong of the same name. Curran, achieving a harmonious union of dexterity and emotion, prays to an unseen god. His limbs fold and unfold in expressions of pleading, supplication, and rapture — the story and the storyteller on a journey from darkness to light.

Dublin-born John Scott brings the esoteric universe of German and Italian opera to a more accessible level. Using text, vocalizations, and choreography, Scott capers between two selves, human and mythological, creating an environment where evil conquers darkness and the need for escape is imminent. His singing voice — a colossal, reverberating tenor, — shoots through the space like a comet.

He instructs us to move our chairs and scatter them throughout the performance space, thus making us an integral part of the piece. At one point, Scott runs through us as if he were Siegmund and we were trees in the forest of Richard Wagner’s Die Walküre. Later, he throws himself to the ground in tragic defeat. Toward the end, he instructs us to join hands, feel the power of connection, close our eyes, and vocalize a tone together. We hum until the air is alive with our combined vitality. As we open our eyes, smiling around the room at one another, the evening’s broader themes come home: we all represent wide perspectives of national identity, and our influences on the world are both universal and uniquely individual.