IMPRESSIONS: Marjani Forté-Saunders Performing Blondell Cummings’ "Chicken Soup"

Presented by Danspace Project

Chicken Soup (1981) Sound Design:

Music for Voice and Glass: Meredith Monk and Percussion and Glass // Colin Walcott from Our Lady of Late (The Vanguard Tapes, 1973) and Brian Eno Ambient 1: Music for Airports // Text from Enormous Changes at the Last Minute by Grace Paley, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974 // Recipe from The Settlement Cookbook // Excerpt from Poem by Pat Steir, Kitchens, 1970

Additional Sound Design and Reconstruction for Chicken Soup (2025):

Everett Saunders/7NMS

Media Design: Meena Murugesan

Lighting Design: Kathy Kaufmann

Ritual: A ‘Chicken Soup’ Annex guest artists: Nia Love, Edisa Weeks, Charmaine Warren, Marýa Wethers, Tara Willis, Davalois Fearon, Camilla Davis, Idea Viola Reid

Co-Presented by the City of Santa Monica Cultural Affairs Division

Dates: May 29 - 31, 2025

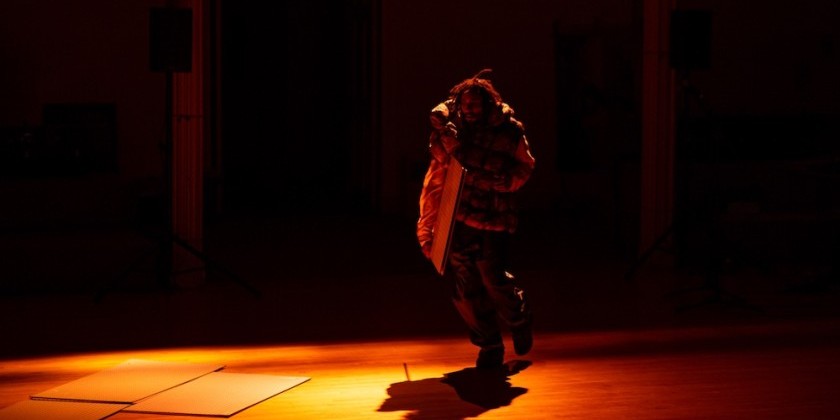

Marjani Forté-Saunders, a powerful and riveting performer who inhabits character as closely as a hand in a glove, revisited Chicken Soup, Blondell Cummings’ seminal 1981 solo, at Danspace Project this past month. Commissioned by Danspace to mark its 50th anniversary, the danced was named an American Masterpiece in 2006 by the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2007, Forté-Saunders became one of a small circle of dancers over the years to have been sanctioned by Cummings to perform the work.

It’s easy to see why Cummings, a master of character-driven performance, mentored the then-23-year-old Forté-Saunders. Now 41, she brings a fierce vitality to this hardscrabble piece, in which a Black woman scrubs the kitchen floor, cooks a healthful dish, and reminisces about family and friends. Cummings drew from childhood memories of her grandmother’s kitchen, a space where a close coterie lovingly gathered. Cummings insisted Chicken Soup was an apolitical portrait of her grandmother, countering at least one white critic’s interpretation. Forté-Saunders’ version, however, is unmistakably a dance of protest, especially in the context of our current political climate.

Cummings’ work spanned multiple disciplines that included film, photography, poetry, and oral history, reflected in her role as a founding member of Meredith Monk’s multimedia ensemble, The House. Forté-Saunders charts a similar path, creating award-winning, multidisciplinary works that also push boundaries.

This latest Chicken Soup enlarges the original and expands the discussion. Sprigs of lavender line the edge of the St. Mark’s Church sanctuary, suggesting spiritual protection. This dance is performed in a sacred space within a sacred space, as if to say the dance itself is sanctified. Above the altar, projections read: “Entrenched system of violence... We shall prevail... Teach our nervous systems that we are powerful... We move into unfuktibility,” followed by black-and-white footage of Cummings at her enameled kitchen table, wearing a ruffled white apron.

Forté-Saunders comments, “I love the honesty she moved with. I can tell she was telling the truth on every level.” I saw a performance of Chicken Soup in the 1980s and what stayed with me was Cummings’ utter veracity.

A 6:35-minute film of Cummings from 1988 loosely outlines the structure of Forté-Saunders’ version: the swinging brown paper bag, the stop-start realism of seated gestures, the fierce African-inflected-dance with frying pan and percussion. The kitchen becomes a metaphor for both physical and emotional safety even as Forté-Saunders reaches into the sanctuary’s vast space. The tension between interior and exterior, realism and surrealism, remains central.

Seated in a slatted-back chair to melodic piano music, Forté-Saunders silently and exaggeratedly mouths Cummings’ recorded words: “The table was an enameled table, common to our class, easy to clean.” She mimes stirring the contents of a bowl, sipping from a glass, whispering into an imagined friend’s ear as the recording plays, “All summer they drank iced coffee with milk in it... but rarely laughing. Endlessly talking about childhood friends, operations, and abortions, death and money.” The recipe for chicken soup is recited. Instead of Cummings’ worn dishtowel, Forté-Saunders wields a shimmering gold cloth, which slaps the air around her turning and bending body. Like Cummings, she mouths a desperate silent scream, but unlike her predecessor, she ends with a raised fist, a gesture of political resistance. One of the most beguiling images follows when her sorrowful shadow, magnified tenfold and ghostly, appears on the altar wall. Touchingly, a second giant shadow reaches to comfort. The source of this second body, mysteriously, remains unseen.

The frying pan dance is set to a soundscape of gurgling water, struck glass, and rhythmically moving fingers. “I feel like I’m falling in love,” Forté-Saunders says. She soon climbs into the audience, selects an audience member, and mimes feeding her. Scooting back onto the stage, she swings her body upstage, and she herself, tastes the invisible food.

Projected next is a film of endless waves from a boat at sea, suggesting the forced journey of enslaved Africans on the Middle Passage. Then seven multigenerational women, dressed in white (white evokes spirituality and healing), pound the floor with their feet and gesture with their hands. Who do they represent? Cummings’ kin, women everywhere, the 12.5 million enslaved Africans? Perhaps, all. Spray hits the camera lens as the performers slowly clump to form a sisterhood, gathering once again at the metaphorical kitchen table.

.jpg)

After the performance, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Cummings’ longtime friend and a fellow choreographer, led a discussion ("longer than the dance," remarked the person seated next to me; a second Cummings dance would have been welcomed). Both Forté-Saunders and Houston-Jones noted that Cummings could be cantankerous (her family in the audience chuckled in agreement), but generous, too. Forté-Saunders recalled long sessions exploring movement scores and Cummings’ advice to “pull on things you know with your mother.” She added, “The greatest entry that Blondell gave me was to source myself.” When asked what Cummings might have thought of the liberties taken in this expanded version, Forté-Saunders replied, “She was an experimentalist” and would have encouraged the broadening of the legacy.