IMPRESSIONS: Lucinda Childs’ “Dance” at The Joyce Theater

October 19th, 2021

Choreography by Lucinda Childs

Music: Phillip Glass

Film: Sol Lewitt

Performance: Robert Burke, Katie Dorn, Sarah Hillmon, Sharon Milanese, Patrick John O’Neill, Matt Pardo, Lonnie Poupard Jr., Caitlin Scranton, Shakirah Stewart

Polyester, bell-bottoms, and disco? Not much from the year 1979 feels particularly relevant to our modern age of social media and smartphone technology, where art is increasingly consumed in short, snappy tidbits. And yet, Lucinda Childs’ Dance, commissioned in 1979 by the Brooklyn Academy of Music and created in partnership with composer Phillip Glass and filmmaker Sol Lewitt, continues to captivate audiences with its mesmerizing repetition and evolving geometric shapes. Through the brilliant overlay of Lewitt’s film, the current company appears to move alongside the original cast. The result crafts a world where past and present exist simultaneously.

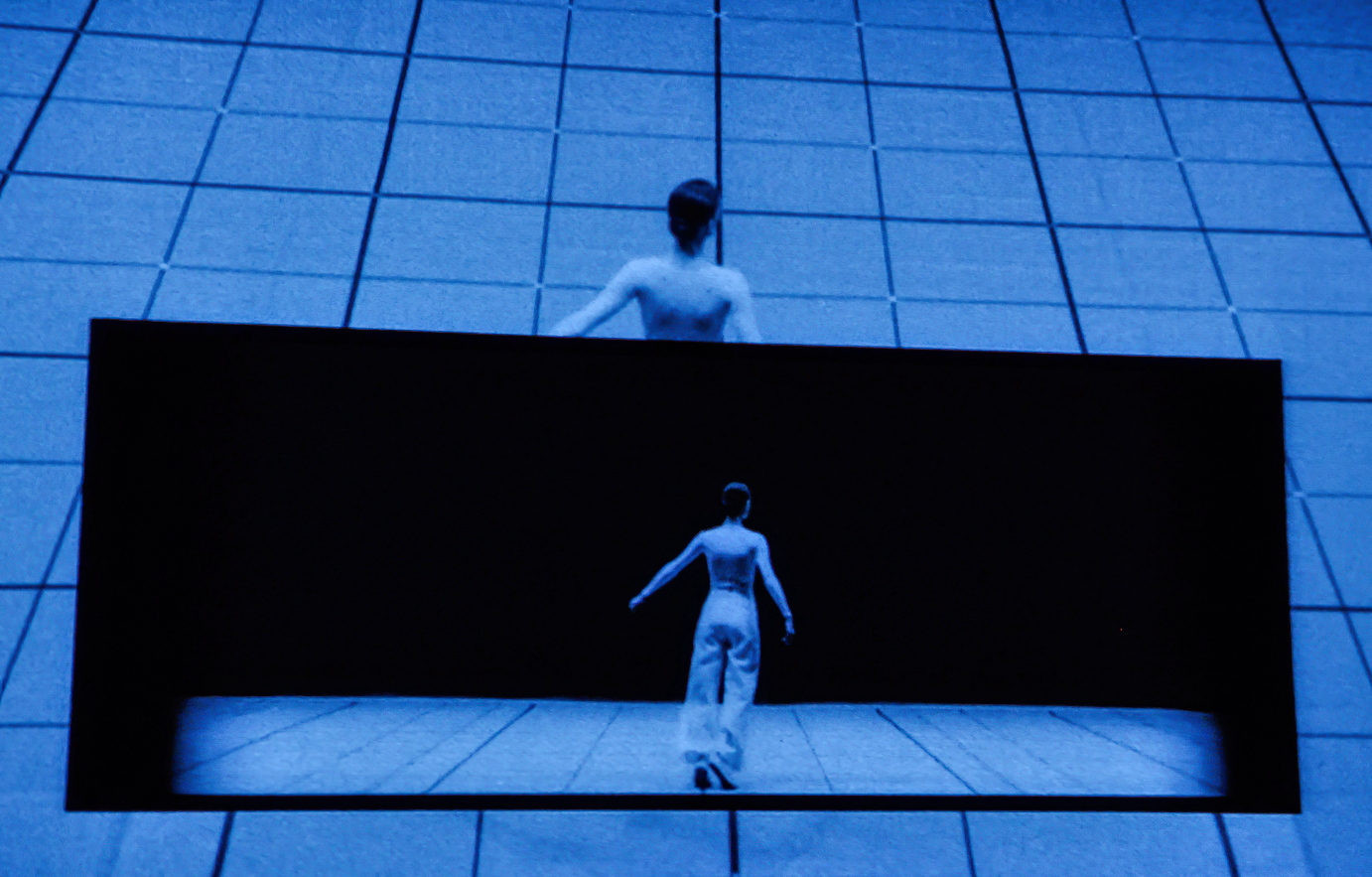

Dance opens with a sequence of crossings. The dancers, resembling cascading snowflakes in long-sleeved white leotards and loose white pants, sweep across the stage with three simple steps: a lunge, a skip, and a sideways leap. The live artists are joined by projections of the original members, captured in Lewitt’s film, which is mounted on a transparent screen descending from the ceiling in front of the stage. A ghost-like quality pervades as the dancers in the film appear and disappear. Sometimes, they are layered directly on top of the live artists, and sometimes they are stacked above them.

Eventually, a catch step is added to the three-step sequence. Larger groups emerge, sometimes weaving through each other as they cross the stage. Childs blossomed out of the Judson Dance Theater scene of the 1960s and 1970s, and we see that influence in her movement vocabulary. She fuses pedestrian movements like walks and pivots with classical ballet steps stripped of stylistic flourishes. Tiny moments of counterpoint manifest, like when one dancer does an additional step, and the other does not.

.png)

Childs develops excitement through repetition. Rather than lulling us to sleep, the persistent redundancy in both music and dance builds momentum. We are hypnotized into attention. Dance feels like watching a spider weaving its web; simple steps and geometry evolve into immensely complex patterns.

The film becomes more intricate as the work progresses by layering additional footage. At one point, the entire screen shows the zoomed-out version with the full cast, while a smaller square in the center narrows in on a few dancers, who move in and out of the frame. At times the dance floor, composed of big, white squares, is visible, and other times the background is black. The film plays with time as when a solo dancer is repeatedly frozen in moments of transition.

Two group pieces (“Dance I” and “Dance III”) sandwich a solo, performed by Caitlin Scranton. “Dance II” is a breathy sequence of steps and turns, in which Scranton uses her arms as pendulums to instigate movement. Childs’ fascination with simple, geometric shapes reveals itself in the spatial pattern of Scranton’s movements. These evolve from a simple line that moves forward toward the audience, and then retreats into a small circle, where she appears to rotate around the soloist in the film.

“Dance III” embeds intricacy into themes from the first section. Movement patterns become less obvious, and at times, the artists appear to dance with one another. As with most things that appear effortless, tremendous focus and concentration are behind the seamless flow. In particular, the mental challenge for the dancers must be immense. After how many repetitions do the sequence begin to morph? How is it possible not to lose count?

The opening-night crowd is bustling and eager, but it wasn’t always that way. Audiences took their time to appreciate Childs’ work (she describes to The Guardian a performance in Minneapolis where almost the entire audience had left by the end). While the joy of Dance is certainly exacerbated by a rare opportunity to leave the house and witness live performance, audiences have developed a firm appreciation for the legacy of Childs and her minimalist movement. In Dance, perhaps her most enduring work, Childs has created a piece that defies both time and space.