AUDIENCE REVIEW: "Touche" Review

Company:

ABT

Performance Date:

November 23, 2020

Freeform Review:

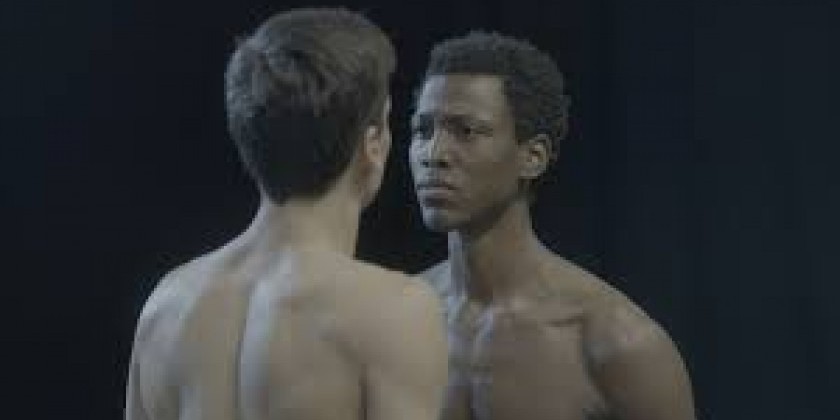

“Touche”, choreographed by Christopher Rudd for the fundraiser performance “ABT Today: The Future Starts Now”, is one of multiple pieces featured in a collection of performances that was created to support the ABT RISE initiative. Christopher Rudd designed “Touche” with a focus on “normalizing gay love and lust in society.” Gay love is supported and recognized in theory, most visibly through the Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges which legalized gay marriage throughout the United States. But in reality, it is not yet accepted or normalized in the same way straight love is. While Rudd choreographed this piece as a pas de deux between two male dancers, a third looming presence persists throughout the piece. Christopher Rudd utilizes light in “Touche” as a tool to reflect the marginalization of the gay community by society, specifically in categorizing its members as those who live in the darkness of the metaphorical “closet”, and those who step out of the “closet” and claim their sexual identities publically. Rudd uses light to demonstrate how “coming out of the closet” is less about society encouraging and allowing members of the gay community to acknowledge and accept their sexual identities, but it is instead more about society being able to fetishize the process of “coming out of the closet” in order to distinguish who is gay from who is not. Society invades the lives of gay people by making their sexual identities a public spectacle through the forced process of “coming out of the closet”. Rudd skillfully uses ballet dance as a vehicle to defy the standards and expectations implemented by traditionally gendered ballet choreography by featuring, embracing, and acknowledging gay love for what it is, and not for what society would like it to be.

In the beginning of the piece, the two dancers are shown wearing sweaters and khakis.

At a first glance, the dancers can only be identified by their colloquial, everyday clothing, which makes them appear extremely normal. Their clothing, which is bland and unassuming, allows the dancers to live freely in society without suspicion that they may be gay. The dancers are configured in a weight bearing position in which they are bending their backs and reaching their arms in a way that enables them to grab one another’s heads for support. This weight bearing position clearly requires trust from the two dancers, as the position is sustained only through the connection of their heads, despite the rest of their bodies being detached. The connection in the dancer’s heads juxtaposes the separation that exists between the rest of their bodies to symbolize the social barriers that invalidate physical connection between people of the same sex A mental connection between people may not be as noticeable as a physical connection, which is why the dancers are able to sustain a connection between their heads and not through the rest of their bodies. This very moment in the piece begs the question: do we live in a society where people of the same sex can freely explore, express, and act on an internalized love or lust without scrutiny?

This first moment occurs in darkness, but when the light illuminates the space and reveals the position that the dancers are in, they become extremely tense and anxious, as if they were caught acting sinfully and shamefully in broad daylight. They break out of the first position and stand back to back, conveying a sense of solidarity in their feelings of anxiousness and fear. The visible tension that creeps into the dancers’ shoulders and torsos suggests that their choice to stand back to back was not entirely based on their own personal desires, but rather based on the presence of the light, as if it was the light that directed them to lose contact from their first position. The dancers’ reaction to being illuminated indicates that exploring a connection with someone of the same sex can only occur comfortably in the darkness, and makes the dancers feel that they should keep their identity closeted and hidden in the shadows. By subjecting the dancers to a sense of mistrust in the presence of the light- or society- the dancers feel as though their identity is only welcomed in society, so long as it is “closeted.” Light, which usually symbolizes safety and freedom, forces the dancers in “Touche” to either come forward about their sexual orientation, or hide their identity in the darkness of the closet that society has constructed. The dancers are made to feel obligated to bring their identities to light, rather than having society learn to accept these men as they are.

The dancers advance into a sequence of movement until their hands make contact, which causes them to unexpectedly break apart from each other. They start to beat on their own chests with their fists, and in doing so, the dancers begin to punish themselves for entertaining lustful and sinful ideas with one another. The beating of the dancers’ chests can also be interpreted as a symbol of strength and masculinity. The dancers’ are reminding themselves that their natural desires are incompatible with society’s idea of how they should go about their lives as men. While the beating of their chests appears as a form of self correction or self punishment, it is clear that the true pain the dancers feel in this moment is their inability to freely pursue love in a society that does not recognize this love as valid and normal. There is an incredible conflict the dancers face in acknowledging that they want to be able to give themselves the opportunity to love, but are kept from doing so because of societal norms and ideals.

The dancers eventually start to interact with each other again, and they begin to lift and support one another in such a way that reflects on the dancers’ budding lust and curiosity. The dancers are beginning to give into the desire that they have for each other, but are still unable to look directly into each other's eyes. In doing so, they would have to accept the fears that they have of publicly entertaining a sexual connection with someone of the same sex. Their dancing is abruptly interrupted by a mysterious outside force, to which they sharply direct their gaze and attention to. It is evident in this moment that they see that someone is watching them, and they become more fixated on the idea that someone may know their secret rather than on their undeniable connection. They protect each other from this public scrutiny while they cower deeper into the darkness, a space that society denotes as gay people’s safe space.

Eventually, the dancers find freedom in each other, despite the way that the light, or society, marginalizes them. Toward the end of the piece, they mutually decide to remove their clothes and strip down to only in nude dance belts. As opposed to the sweaters and khakis that hid their identities in the beginning of the piece, the nude dance belts enable the dancers to be their truest selves in this moment, just as they were born. The nudity presented by the dancers exemplifies freedom and truth, and their newfound ability to live truthfully and pridefully in their own skin. The dancers allow themselves to explore being playful with each other, and through their movements, they communicate a sense of gratitude in being able to share and connect with each other in a way that they have never been able to before. They finally kiss each other, and in doing so, a black out occurs.

In the beginning of the piece, the darkness was a place where the dancers could feel safe from public scrutiny, but still maintain feelings of shame and humiliation in their identities. In the final moment of the piece, however, they do not feel shame for existing in the darkness. Rather, they feel content and liberated insofar as they can now share any space, light or dark, with each other. This use of light aims to communicate that as a society, we should not put the gay community in an “Other” category. Christopher Rudd’s piece is successful in advancing not only how we see dance, but how we see love. Love comes in all forms, and exists between a variety of people. Regardless of how society categorizes people, we should accept everyone as they are, however publicly or privately they choose to live out their identities.