IMPRESSIONS: Experiments in Art and Technology “9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering” at Anthology Film Archives

Directed by Barbro Schultz Lundestam and Julie Martin

Edited by Barbro Schultz Lundestam, Julie Martin, and Ken Weissman

Produced by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin for Experiments in Art and Technology (1966-2013)

Performances curated by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver

Works by Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, and Yvonne Rainer

It doesn’t get much better than the cozy embrace of a darkened movie theater on a cold and blustery weekend—for me, it’s second only to an equally cozy performance space. Film and performance have long gone hand in hand, with ample evidence of this creative dialogue on display at Anthology Film Archives, which hosted screenings of ten documentary films about the 1966 avant garde performance series “9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering.” Experiencing these rare archival films offered an opportunity to reflect the generative possibilities at hand where art meets technology.

Fittingly, the original “9 Evenings” performance series was an undertaking of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which brought together ten experimental artists and thirty engineers from Bell Telephone Laboratories to innovate at the intersection of their disciplines. The collaborations were spearheaded by Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver and artist Robert Rauschenberg, who leveraged their respective community connections to play matchmaker by asking artists to dream up a creative vision and pairing them with engineers who could help make it possible (spoiler alert: dreams were not always made reality). Together, each group came up with something unexpected—a more than satisfactory outcome in the highly experimental creative climate of the 1960s that blurred binary metrics of “success” and “failure”—and the process challenged everyone involved, at times shifting and influencing their later interests and practices.

The series featured creations by four icons of postmodern dance: Steve Paxton, Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, and Yvonne Rainer. On the heels of their Judson Dance Theater experiments, “9 Evenings” captured these four dancemakers as they emerged into independent, yet still interconnected, practices. While their social and creative worlds overlapped considerably and they continued to perform in one another’s work, each artist pursued a distinct avenue of curiosity to extend their choreographic modalities across media.

The films combine original footage from the October 1966 performances with interviews with the artists and engineers, conducted in the 1990s when the performance footage was recovered and restored. The performance sequences, shot primarily in black and white with occasional full-color clips and recorded audio overlay, show the palpable buzz (and at times, utter confusion) of audiences and the thoroughgoing presence of performers. Each performance found its own way to activate the cavernous expanse of the 69th Regiment Armory through interactions of sound, light, images, objects, and movement. While radically distinct from one another, a continual interface between bodies and technology ran through the series, underpinned by an abiding sense of risk.

%2C%20photo%20credit%20Adelaide%20de%20Menil.jpg)

Paxton and engineer Dick Wolff’s “Physical Things” explored the choreographic potential of materials by funneling the audience through a monumental inflatable architecture of plastic sheeting. Performers daubed in liquid crystal body paint inhabited the diffuse glow of the billowing maze, their bodies blurred from the view of curious voyeurs outside as an overhead network of radio signals responded to their movements. The footage certainly misses more than it captures of this work, which speaks to the highly individuated and subjective experience of every person involved.

In “Vehicle,” Childs worked with Peter Hirsch to devise motion-activated sound environments through the interruption of a sonar beam—glowing buckets swung in pendular arcs, a passive body balanced inside a hovering glass enclosure (levitation was a common aspiration among the artists)—while shifting pulses of light cast distorted shadows on surfaces to trouble the distinction between an object and its image. Meticulous planning and methodical execution lent this work a clean, cool surface that smoothed its dissonant textures and improvisatory edges.

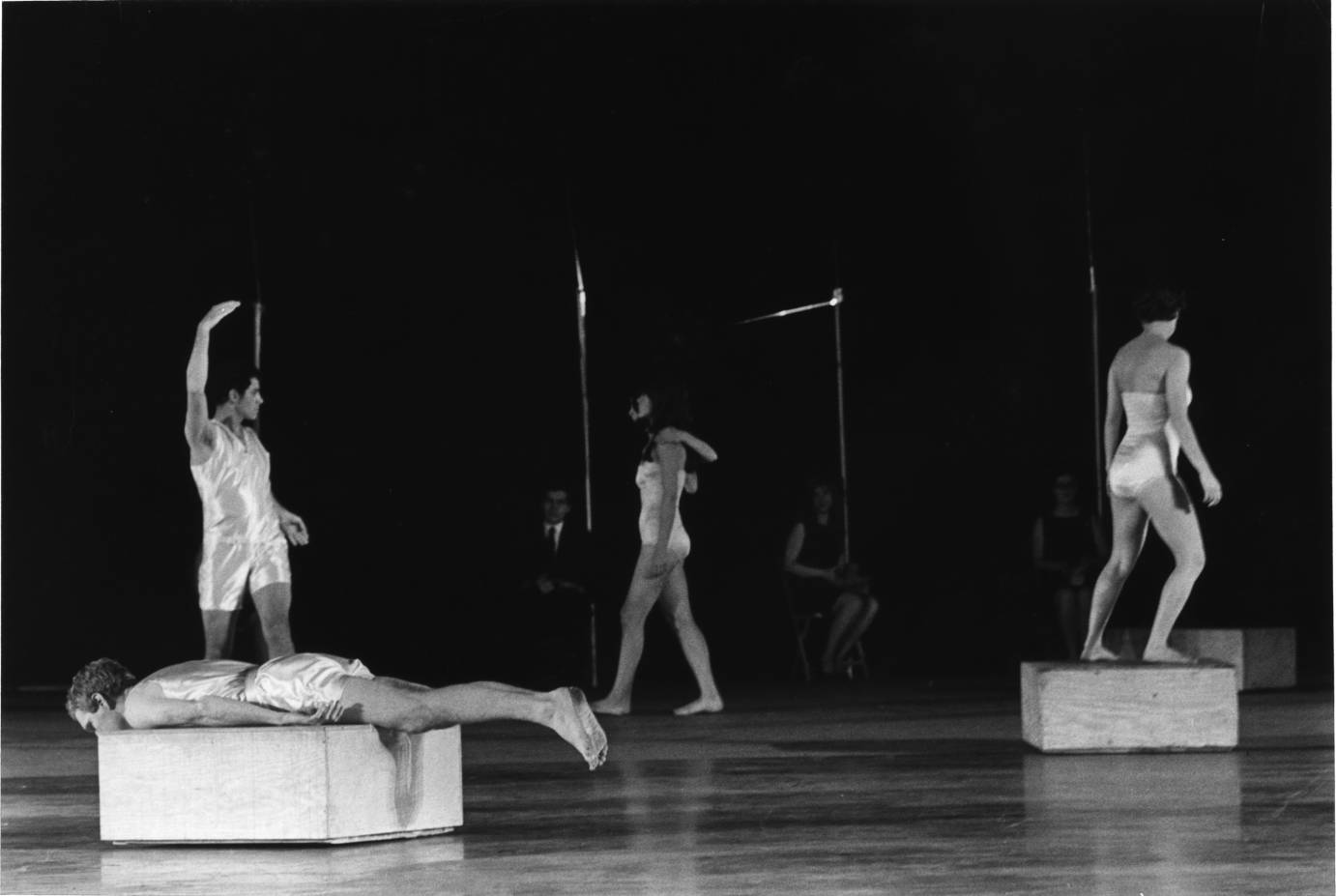

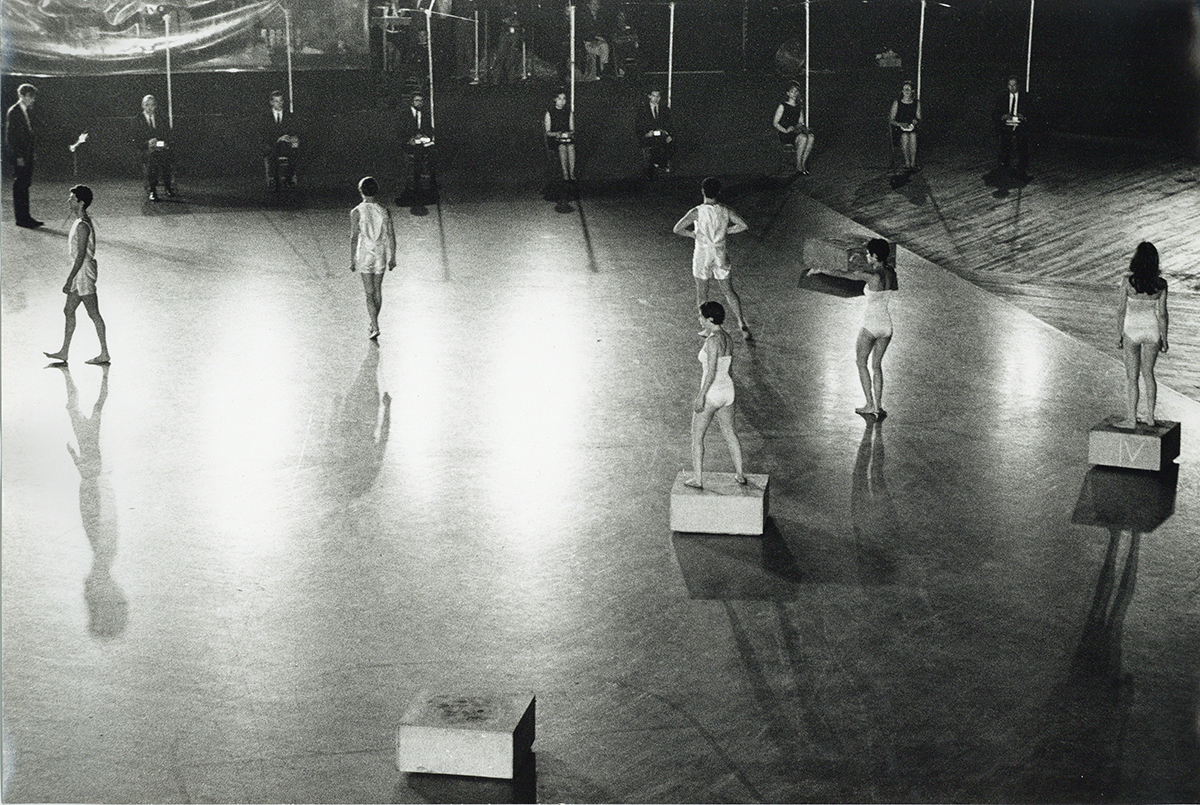

For Hay’s group work, titled “Solo,” the artist partnered with Larry Heilos and Witt Wittnebert to create shifting spatial landscapes: sixteen bodies dancing in concert with eight wheeled platforms guided by an ensemble of remote control operators. Performers could walk around the space or step onto a platform to float from here to there, suspended in slow, sculptural pulsations or frozen like mannequins. While “Solo” hewed closest to what might be recognized as a work of dance, its choreographies transcended the shape and form of bodies to sculpt space and time through emptiness and stillness.

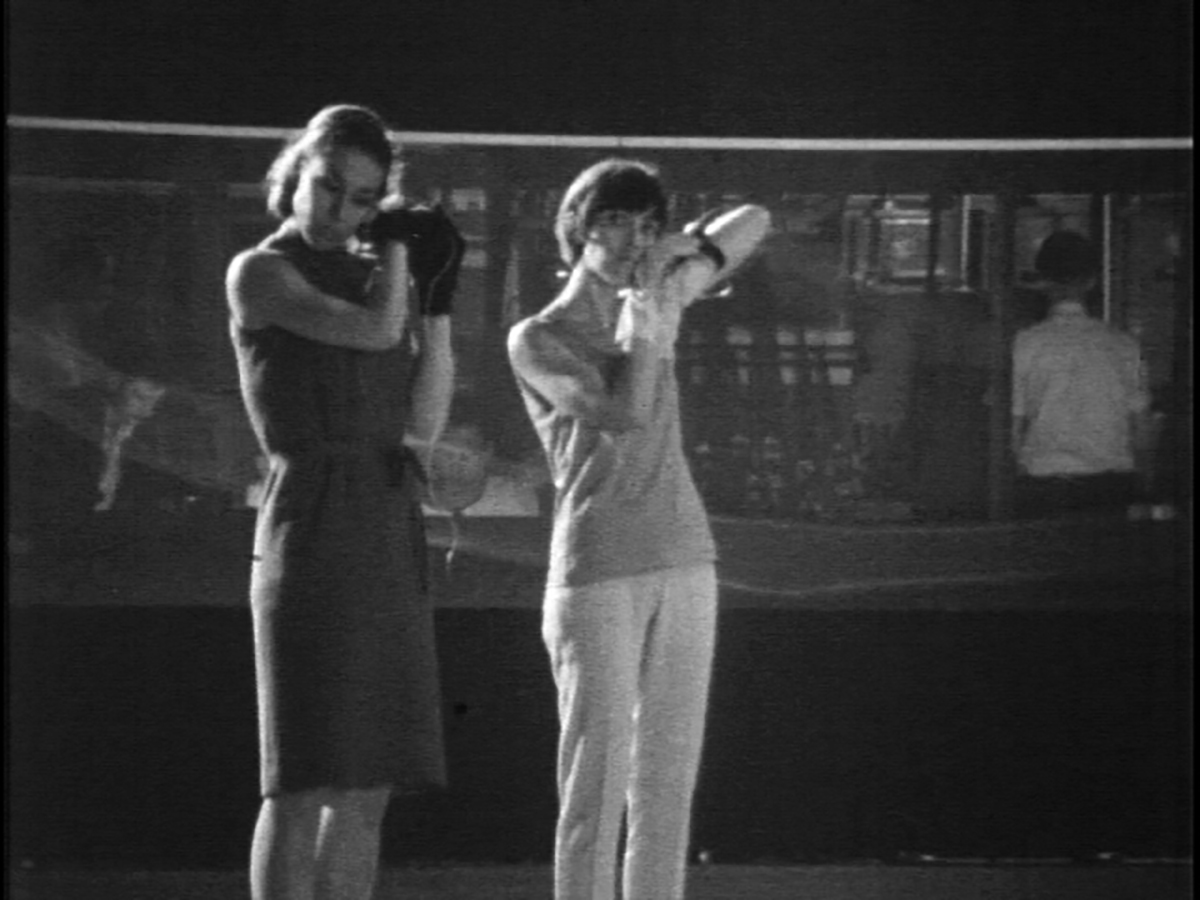

Rainer dug into the pedestrian vocabularies of her Judson-era work while extending these forms through technological intervention and juxtapositions across form, tone, and space. Her and engineer Per Biorn’s “Carriage Discreteness” layered a meandering recorded conversation about embodied and social erotics with the sparse, everyday movements of fifteen performers carrying objects around the space, their postures shaped in turn by the materials they handle and the directives parsed out by an omniscient voice on walkie talkie. Paxton made an arresting appearance as a serenely passive body on a 50-foot swing strung from the lofty rafters of the Armory—one of an array of mechanized objects that activated the upper space of the performance arena.

In their reflections decades after the performances, each artist seemed to have come away from their project changed in some meaningful way. Paxton showed good-natured frustration with his project’s material complexity and relished a return to solo dances done to recorded music; the film closes with a snippet of his casually virtuosic improvisations to Bach in the sanctuary of St. Mark’s Church. Childs, on the other hand, continued to explore experimental collaborations with an increasingly refined attunement to formalism through her hallmark minimalistic complexity—one could even say she has an engineer’s mind for dance. While Hay initially struggled to come up with an idea for the project—imagination paralysis, perhaps—she ultimately found a unique opportunity to think differently and aspire to new levels of collaborative inquiry and exchange. For Rainer, the project served as a bridge between her early postmodern performance and the experimental film work that would comprise much of her later career, and while she stated that she might have done things differently in retrospect, what mattered most was the attempt. All told, “9 Evenings” seems to have served as a watershed moment in postmodern experimental performance, driving the form forward through the confluence of cutting edge technology and radical creative imagination.

While we may not have a consolidated forum like E.A.T. or “9 Evenings” today, cross-disciplinary conversations and creative collaborations continue to blossom amid exponential technological innovation. More and more, I’m seeing the role of “creative technologist” emerge as a key collaborator in performance projects, which shows me that artists working in performance are actively thinking about how to harness technologies beyond traditional stagecraft as integral parts of their creative processes. “9 Evenings” may have attempted something unprecedented and as yet unrepeated, even arguably unrepeatable; still, Rauschenberg’s use of “The Beginning” for the end titles of these films proves a prescient choice—E.A.T. had only just begun to set new lines of collaborative inquiry in motion.