IMPRESSIONS OF: Laurie Anderson's "Habeas Corpus"

At the Park Avenue Armory

Oct. 2-4, 2015

Laurie Anderson

With appearances and/or work by: Mohammed El Gharani, Shahzad Ismaily, Merrill Garbus, Stewart Hurwood, Omar Souleyman

Including music by Lou Reed

“Smoking or non-smoking?” Laurie Anderson asks, her voice purring as she reprises her 1981 hit “O, Superman,” at the Park Avenue Armory. Despite her ironic tone, the answer is clear. Massaging the keyboard and thrilling the audience gathered at the foot of the bandstand in the Armory’s Wade Thompson Drill Hall, in New York, Anderson is definitely smoking.

The Pop diva of performance art, Anderson wrote “O, Superman” in response to the failure of American military power during the Iranian hostage crisis; but twenty years later her song, with its “here come the planes, they’re American planes,” seemed astonishingly prescient when terrorists hijacked commercial airliners and flew them into the Twin Towers.

Now “O, Superman” is doing triple-duty as Anderson tackles a related subject, the US government’s mistreatment of a man named Mohammed El Gharani. His unlawful kidnapping, torture and off-shore imprisonment at Guantánamo Bay are the focus of “Habeas Corpus,” an extraordinary art installation and concert series that ran Oct. 2-4. The details are almost too hot to handle; and for all her gentleness Anderson is crackling with righteous indignation.

Here’s the backstory. U.S. agents seized El Gharani in Pakistan when he was 14 years old, although he was not a terrorist and was innocent of any crime. In 2009, after he had suffered in captivity for seven years, the courts forced the government to release him. They shipped him off to West Africa, the land of his ancestors, without so much as an “oops, sorry;” and like all former inmates at Guantánamo he is forbidden to enter the United States, where he might tell his awful story to the American public. The government’s security apparatus is determined to conceal its misdeeds and incompetence under a giant burqa of secrecy.

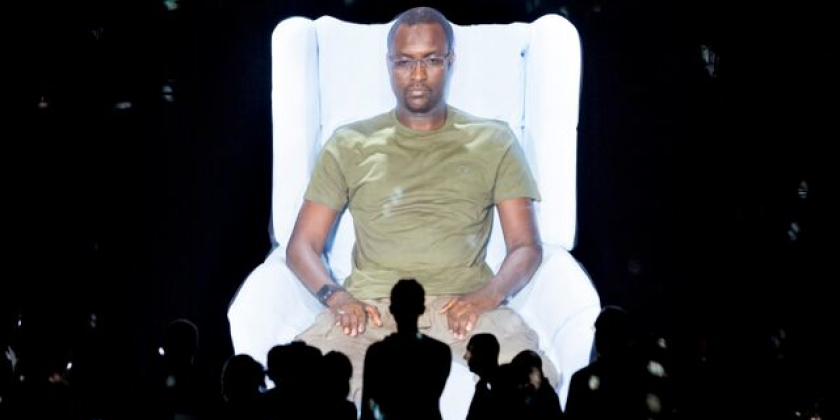

Anderson’s ingenious solution in “Habeas Corpus” is to beam-in the former prisoner, giving him a virtual presence as a three-dimensional projection 10 times larger than life, which looms at one end of the vast Drill Hall. Simply dressed in a green T-shirt and slacks with his tennis shoes half-laced, El Gharani appears seated in a Brobdingnagian armchair specially carved to give his image depth. Intended to recall the sculpture of Abraham Lincoln that greets visitors to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., this 21st-century image, in living color, also becomes a monument to the heroism of an ordinary human being, who suffered needlessly and unjustly but who managed to embarrass his captors by surviving to reveal the truth.

Anderson has a personal history with what she calls “telepresence;” and holograms are all the rage these days. They enabled persecuted journalist Julian Assange to drop in on a conference while still confined to the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, and, even more surprisingly, they will allow Whitney Houston to embark on a posthumous world tour next year. But it must have worried Anderson and her colleagues when, in July, Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel issued a fatwa forbidding a holographic performance by rap artist Chief Keef, forcing the benefit for Keef’s “Stop the Violence Now Foundation” to become a rave-style event with the musician’s image projected at a secret location. This chilling act of censorship made Anderson’s work all-the-more timely, if such a thing were possible.

“Habeas Corpus” would be important, anyway, since, as the title reveals, this piece is not simply about one prisoner but about the protection against unlawful imprisonment written into the U.S. Constitution. This protection was not slipped in surreptitiously, when our rulers weren’t looking. The framers of the Constitution laid it there deliberately as a cornerstone of our liberty; and the government’s legitimacy rests upon this foundation of freedom. If the empire that was never supposed to be an empire now feels threatened, teetering on the verge of panic, it is partly because our government has stripped itself of the Constitutional guarantees that were its moral defense and the only justification for its continuing existence. Anyone who finds it presumptuous to display El Gharani’s image on a scale comparable to that of Lincoln’s should consider that no Drill Hall would be large enough to contain the magnitude of the U.S. Constitution’s shield of freedom, and that this document was not written to safeguard the rich and powerful but precisely to defend the common man and the oppressed.

The “Habeas Corpus” installation remains open throughout the afternoon, giving unhurried visitors time to think beginning by reading the placards flanking the entrance. Each bears a message from our Founders. These reminders appear suddenly, blinking on our mental screens like warnings tweeted from the past. “…the practice of arbitrary imprisonments have been, in all ages, the favorite and most formidable instruments of tyranny,” writes Alexander Hamilton.

Entering the Drill Hall visitors then plunge into darkness, the emptiness speckled with hundreds of points of light. A giant disco ball hangs over this wasteland like the Eye of Sauron, its faceted mirrors glancing vigilantly in all directions. Moveable track-lights shoot their beams at the glittering ball in such a way that its constellation of reflections shudders and spins woozily around the visitor. At the far end, the seated figure of El Gharani also appears to move, traveling continuously without ever getting anywhere.

This illusionistic space is borderless, like the so-called “war on terror.” It reflects the disorienting experience of a man kidnapped and spirited to an undisclosed location. Yet El Gharani is not the only one who has been wrenched from his surroundings. We have lost our bearings, too. In Anderson’s installation we can practically watch the outlines of our nation vanishing; dissolving with the framework of the Constitution. “Where is America?” the performance artist asked rhetorically during a press preview, revealing that our moral dislocation is her subtext.

Advancing uncertainly through the shadows, we realize that the floor of the Drill Hall is littered with bodies. Our fellow citizens have camped out on the floor, some of them sitting on cardboard mats labelled “Habeas Corpus.” The cardboard makes these people seem homeless, or like refugees who, reversing the usual sequence of events, have had their country walk out on them. A musician who is part of the installation sits here, too. She plays a trumpet, but her instrument makes weak, burbling sounds, like someone held under water or a torture victim taking labored breaths. Electric guitars strum; and static hisses through the air around us as the late Lou Reed’s score incorporates muted voices captured in surveillance recordings.

Seeing the disco ball overhead, was anyone expecting Gloria Gaynor? Yet in an odd way her defiant 1970s standard, “I Will Survive,” has its place here, too.

Approaching the immense projection of El Gharani, visitors may be struck by his modesty. He raises a hand to flex his fingers and shares a little smile. When he speaks, he gives thanks to his mentor in prison, Shaker Aamer; and he recalls the joy of his own release. El Gharani is solitary here, as he was for years on end. When he isn’t talking, he focuses inward and appears to meditate. His giant eyes, blinking behind glasses, reassure us he’s alive. Unexpectedly he bows forward over his knees and weeps.

In another room labelled “My Story,” El Gharani appears more animated addressing us through the medium of a conventional video recording. Here he extrapolates from his tale, criticizing President Obama for releasing fewer detainees than his predecessor and for reneging on his promise to close Guantánamo. El Gharani also compares his experience to that of the Africans captured and shipped as slaves to the Americas.

The installation features a third room, too, labelled “From the Air.” Like the Drill Hall, this room contains three-dimensional projections, but giving “Habeas Corpus” an “Alice in Wonderland” twist these projections are not huge, but tiny---10 times smaller than life size. The protagonists of this miniature tale are Anderson and her pet dog, Lolabelle, who appear seated side-by-side in doll-house chairs that match El Gharani’s. Speaking in a dramatic whisper, Anderson describes a vacation she took with Lolabelle---a respite from the sirens and terror alerts that had become a disturbing feature of her New York neighborhood in the wake of 9/11. Skipping down the path to the California seashore, however, the innocent pair were attacked by turkey buzzards. Anderson tells us that Lolabelle’s dismay, as she smelled the buzzard’s rotten odor and looked up to see its talons opening above her, reminded the singer of the expression she had seen on her neighbors’ faces in 2001, when they realized they could become an airborne enemy’s prey. Since, in the ensuing years, drone attacks have become a favorite pastime of the U.S. military, perhaps we should make the vulture our national bird.

The evening concerts added some features to the installation, principally Anderson’s performance of “O, Superman,” without changing things substantially. In addition to playing her music, the artist read aloud from poet Alan Ginsberg’s “Song” (“be mad or chill/obsessed with angels/or machines,/the final wish/is love”), and introduced El Gharani.

Bringing in Arabic wedding singer Omar Souleyman to host a dance party seemed like a bust, however, since, at least on opening night, this celebrity DJ couldn’t rouse the crowd. No doubt it did us good to welcome Souleyman in his “keffiyeh” and sun-glasses, and to hear the raucous folk melodies of Syria, but this audience was in no mood for an orgy. We had come to “Habeas Corpus” seeking truth, not forgetfulness.

It’s also hard for a man who has been wearing shackles on his feet to dance. El Gharani admits that after 7 years in those chains, he looked “weird” walking freely around the prison yard. So “Habeas Corpus” is not a dance piece. Nonetheless, we can imagine him joining hands with Anderson and tracing a circle in slow motion. Smiling at each other and almost floating, they celebrate the premiere of “Habeas Corpus,” a piece “dedicated to the freedom and basic goodness of all humans,” and a small, but joyous win over tyranny.