SUMMER IMPRESSIONS: The 45th Anniversary of Mark Morris Dance Group, Old and New, at The Joyce Theater

Choreography: Mark Morris

Musical Direction: Colin Fowler

Dancers: Mica Bernas, Karlie Budge, Sarah Hillmon, Courtney Lopes, Aaron Loux, Claudia McDonald, Dallas McMurray, Alex Meeth, Sloan Pearson, Brandon Randolph, Christina Sahaida, Billy Smith, Joslin Vezeau, Noah Vinson

The Joyce Theater

July 15 - 26, 2025

The most enjoyable evenings of my summer may have been those I spent at The Joyce Theater in July watching two magnificent programs performed by the Mark Morris Dance Group. Kicking off the Brooklyn-based company’s 45th anniversary season, each four-piece program contained a world premiere plus three older works, all choreographed by Mark Morris. I came away awed, as always, by Morris’s extraordinary, oft-touted musicality, but also struck by his equally brilliant, and perhaps under-appreciated gift for drama and theatricality.

Program A: This bill’s main event was the premiere of You’ve Got to Be Modernistic, an exuberant take on early 20th-century vernacular and show-dance moves. The spirited group piece is set to Ethan Iverson’s lively stride piano arrangements of eight tunes by legendary jazz pianist James P. Johnson, including The Charleston, here switched from 4/4 to 5/4 time, so as to be “modernistic,” a concept amusingly reflected in swift bits of rolling modern-dance floorwork Morris inserts amid phrases of Turkey Trotting, cartwheels, Charleston steps, and chorus-line choreography.

However, the highlight of the evening was Mosaic and United (1993), a large ensemble work set to two Henry Cowell string quartets whose “experimental” sounds, I admit, I wouldn’t have enjoyed listening to were it not for the revelatory movements they elicited from Morris. In his “hearing” of the piercing, cold, spare music, Morris finds physical impulses that vibrate, captivatingly shape, and propel the dancers’ bodies in fashions and configurations that recall everyday objects and emotions. Prompting us to experience relationships between this music and our own ways of being in the world, the piece exemplifies why Morris is considered such a remarkable choreographer.

Completing the program was Silhouettes (1999), a wonderfully spontaneous-feeling duet, and The Muir (2010), a balletic sextet seasoned with irreverent humor that felt a bit out of sync with the work’s Romantic-tutu costuming and arty score — nine Irish and Scottish folk songs arranged by Beethoven for a piano trio and three classical singers.

Program B: The more entertaining of the two, this program launched with The Argument (1999), a canny dramatic piece for three couples who perform formal ballroom dance-inflected partner-work to moody Robert Schumann music. Morris’s choreography, in the first part, captures the character of the music, and in the next section responds more directly to the contours of the melodies. A third section mirrors Schumann’s rhythmic timings, while a fourth underlines the music’s accents and changing tempi. But just as one begins to think Morris’s dance should be called “The Elements of Music,” we start to feel a brewing tension. The dancers emerge as individual characters. No longer tightly coupled, some switch partners. And the choreography evolves into breath-taking drama.

Disarmingly clear and gentle — and enhanced by imaginative use of paper fans — the evening’s premiere, Northwest, is a big group work danced to elaborations by composer John Luther Adams on traditional music of the indigenous Yup’ik and Athabascan peoples of Alaska. Inspired by Native American dance, the playful, uncomplicated choreography enchants.

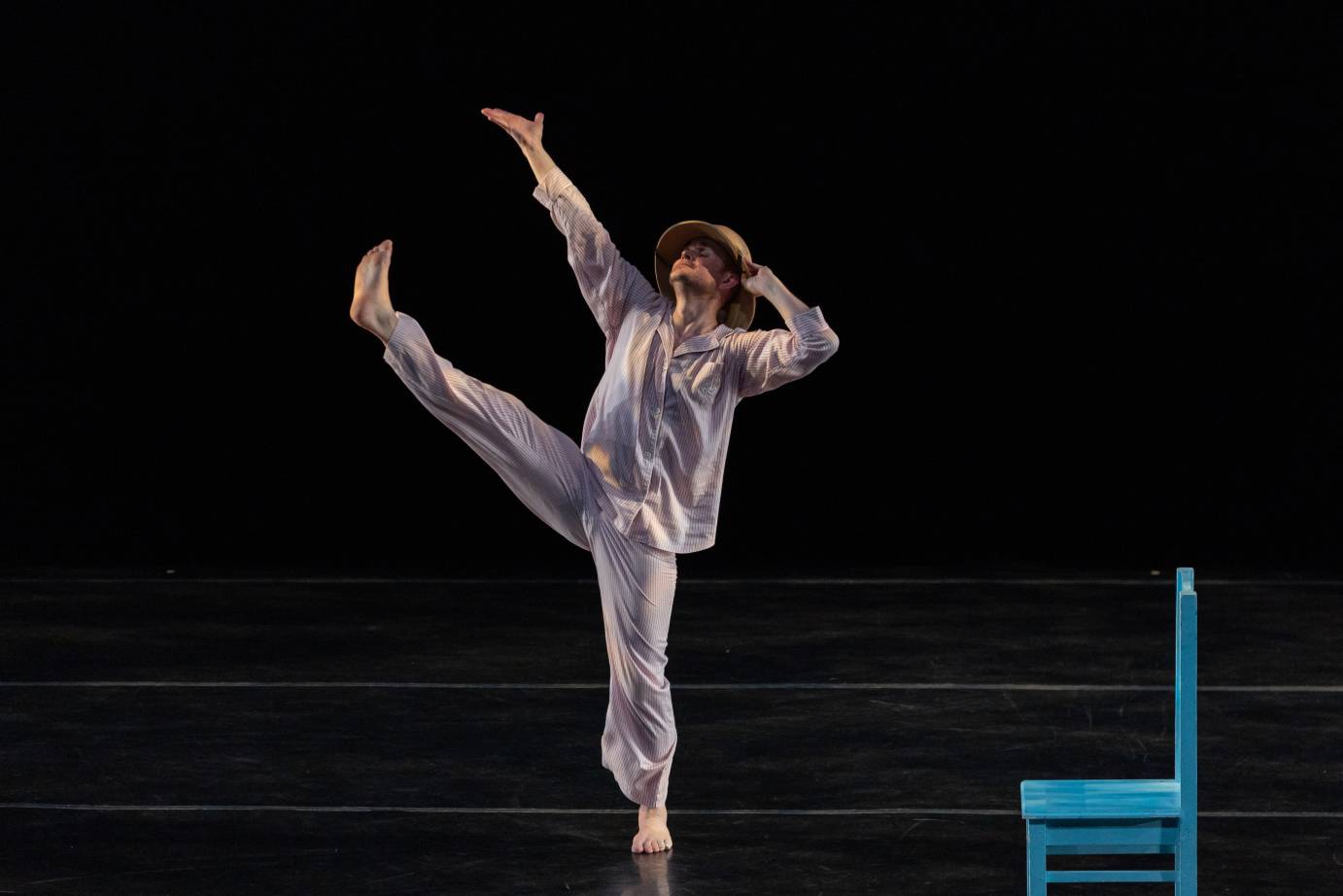

The program ended with dancer Dallas McMurray’s skillful performance of the comical solo Ten Suggestions (1981), followed by the caricature-fueled septet Going Away Party (1990), a delicious parody, choreographed to crying-in-your-beer country-western songs. The highly theatrical closer was hilariously rendered by Morris’s troupe of ace dancer-actors. Yet I couldn’t help but wonder, does the 35-year-old piece poke bawdy fun at rustics in snide ways that, today, might be politically viewed as too representative of a “cultural elite” perspective?