Impressions of Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance

The Limón Dance Company and Paul Taylor Dance Company Perform at Lincoln Center

David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center

March 10 – 29, 2015

For tickets go to David H. Koch Theater

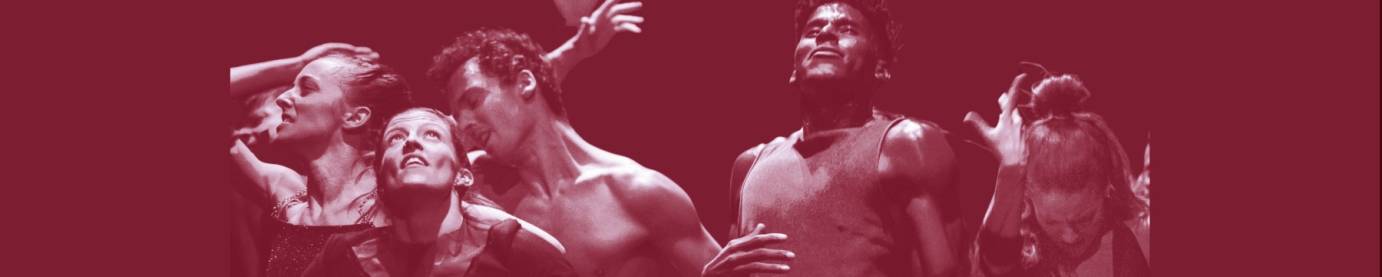

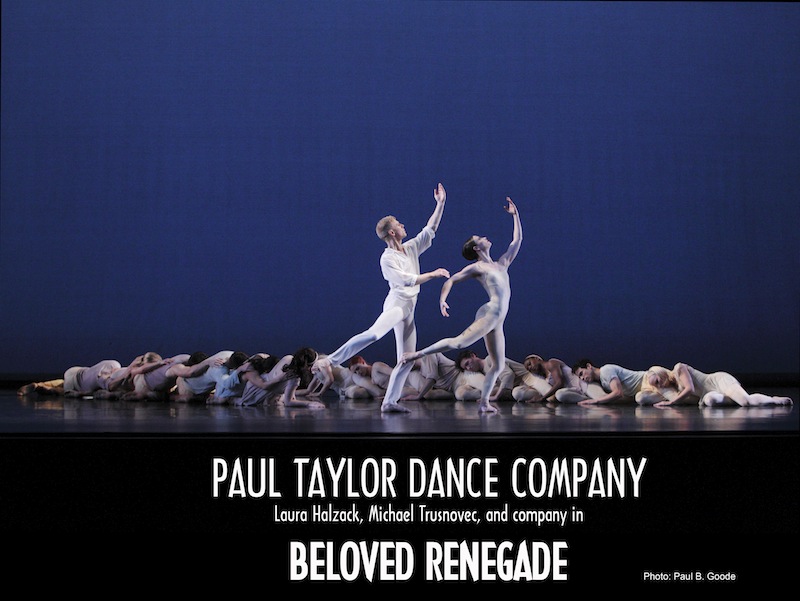

Pictured above: Laura Halzack, Michael Trusnovec and the Paul Taylor Dance Company in Beloved Renegade

Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance presented, for the first time in the troupe’s 61-year history, a work made by someone other than Taylor. For the centerpiece of the triple bill on March 14, the Limón Dance Company made a guest appearance in a performance of Doris Humphrey’s 1938 Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, set to the Bach organ score, which was played live by Kent Tritle.

I had initially feared that the company’s decision to present masterworks by an earlier generation of dancemakers risked turning it into a museum repository for modern dance classics whose lives had run their course. But Passacaglia holds up as a magisterial, moving work that deserves to be seen more often and by a wider audience (the Limón company last performed it in 1978). Is it old-fashioned? Yes—at times, individual steps, massively shaped, have a rather period stiffness. But Humphrey weaves these steps for her cast of 16 into a complex, ever-shifting tapestry with an impressive economy and understated restraint. Choreography at this level never has an expiration date.

Humphrey said of the work: “The minor melody … insistently repeated from beginning to end, seems to say, ‘How can a man be saved and be content in a world of infinite despair?’ And in the magnificent fugue which concludes the dance, the answer seems to mean, ‘Be saved by love and courage.’” This may sound quaintly high-minded, but the passage is important for what it reveals about Humphrey’s keen ear and the drama she hears in the score. For Passacaglia is above all a poignant response to its austere but noble score. When the curtain opens, the dancers, grouped on a three-tiered structure, are seen in silhouette with arms raised. The arrangement suggests an organ’s pipes, and as the work unfolds, the dancers embody the music in ingenious choreographic variations.

Led by a central couple in gold (Kristen Foote and Durell R. Comedy), the dance makes much use of the tiers to create a vertical architecture of bodies, now standing, now seated. At times, the full ensemble dissolves into smaller groups—couples process, four women break into a stately brushing step for a dance of their own—only to resolve again into a unified community. At one point, the group becomes a chorus of pealing bells, as torsos and raised arms tilt in a pivoting step powered by pendulum-like swings of the leg. The bells are a metaphor for the work’s spiritual drama, but no one ever lifts his eyes skyward, beseeching heaven; emotion is distilled into an abstracted response to the music.

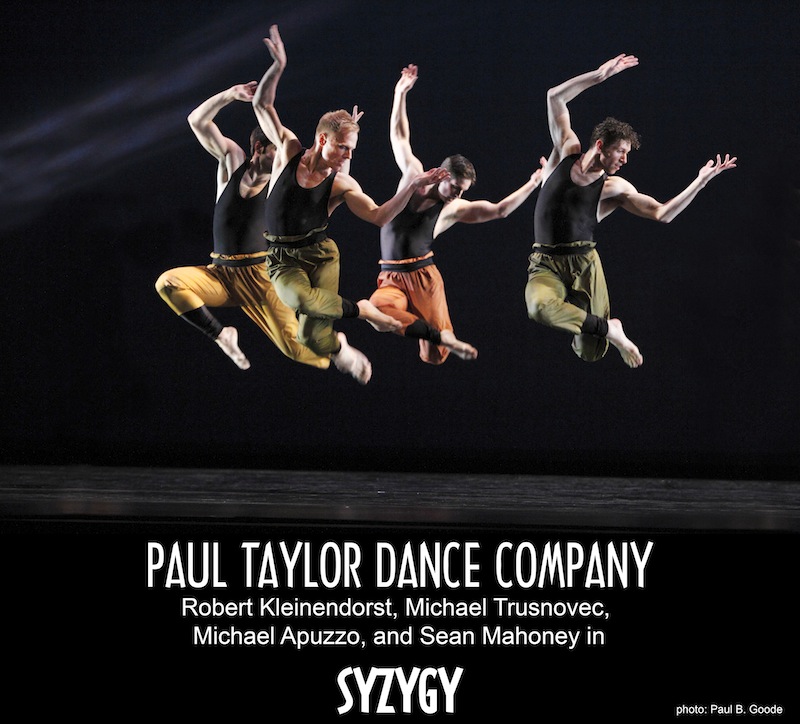

The Taylor works that book-ended Passacaglia were well chosen to complement it. Syzygy (1987), which showcases Taylor at his loosest and most casual, provides a study in contrasts to Humphrey’s dance. It’s a shape-shifting shot of unbridled energy set to a heavily synthesized score by Donald York, who also conducted the evening. The work for 13 dancers showcases Aileen Roehl as an outsider literally dancing to a different beat. She slowly promenades in attitude while the others charge the space with a loose, jazzy movement style inflected with the aggression of martial arts. In a repeated motif, the men, wearing muscle shirts over baggy pants, dive into a back attitude while jabbing a fist into the air. The dancers are hedonistic, self-involved—and uninterested in pairing up. When men and women do dance together, they struggle, the partnering resembling the collision of molecules.

The no-holds-barred dancing is a tour de force for the entire cast, but especially for Michael Trusnovec, whose extraordinarily relaxed coordination gives him a feline ease in the dance’s quicksilver changes of direction. Among the women, red-haired Heather McGinley stands out for dancing that’s fierce and fluid.

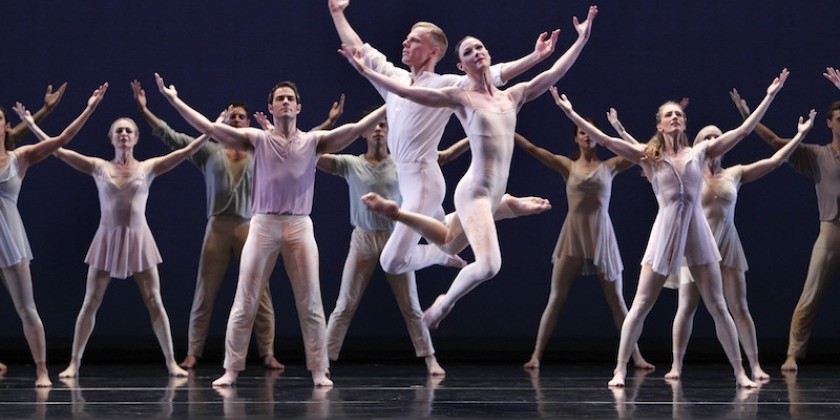

Trusnovec also heads up the final piece, Beloved Renegade. I find this work choreographically less cohesive than that of Taylor’s greatest pieces, but it illustrates his masterful ability to create dances that work on multiple levels and resist simple interpretations. The “Beloved Renegade” of the title is Walt Whitman (danced by Trusnovec), but the figure could equally be Taylor, who is now 84. As Trusnovec stands at the side of the stage watching couples dance in a youthful springtime, it’s unclear if he’s watching them in real time or reviewing scenes in his memory. The work, set to Poulenc’s Gloria, has a valedictory tone as the Whitman figure encounters a woman who appears to be the Angel of Death (Laura Halzack). At one point, Trusnovec collapses in Halzack’s arms, and she tenderly rocks him. In the work’s most indelible image, he lays his head on her shoulder while she shapes her arms in a ring around his waist without touching it—a distance that gives an ambiguous implacability to her comfort. As they stand there, immobile, a small group circles them in a chain dance, blithely heedless.

In the final movement, the singers, led by the soprano Devon Guthrie, cry “Amen” and the Whitman figure takes his leave. The work ends with Trusnovec lying supine as Halzack slowly pivots in a low attitude turn, her raised back leg passing over his figure. Time continues its round even after we are stilled. The program lets Whitman, the consummate optimist, have the final say: “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, If you want me again, look for me under your boot-soles.”