IMPRESSIONS: Trisha Brown Dance Company at The Joyce Theater

Featuring a New York Premiere by Noé Soulier

Founding artistic director and choreographer: Trisha Brown

Associate artistic director: Carolyn Lucas

Assistant rehearsal director: Cecily Campbell

Dancers: Christian Allen, Cecily Campbell, Savannah Gaillard, Lindsey Jones, Burr Johnson, Catherine Kirk, Ashley Merker, Patrick Needham, Jennifer Payán

Executive director: Kirstin Kapustik | Programming director: Jamie Scott

Glacial Decoy

Choreography: Trisha Brown | Restaging: Lisa Kraus and Carolyn Lucas | Visual Presentation and Costumes: Robert Rauschenberg | Lighting Design: Beverly Emmons

In the Fall

Choreography: Noé Soulier | Sound: Florian Hecker | Lighting Design: Victor Burel and Noé Soulier | Costumes: Kaye Voyce

Working Title

Choreography: Trisha Brown | Music: Peter Zummo, Six Songs (Suite for Lateral Pass); Sci-Fi, Slow Heart, Song VI, Song IV | Musicians: Mustafa Ahmed (percussion), Guy Klucevsek (accordion), Arthur Russell (cello and voice), Bill Ruyle (marimba and table), Peter Zummo (trombone) | Lighting Design: Beverly Emmons

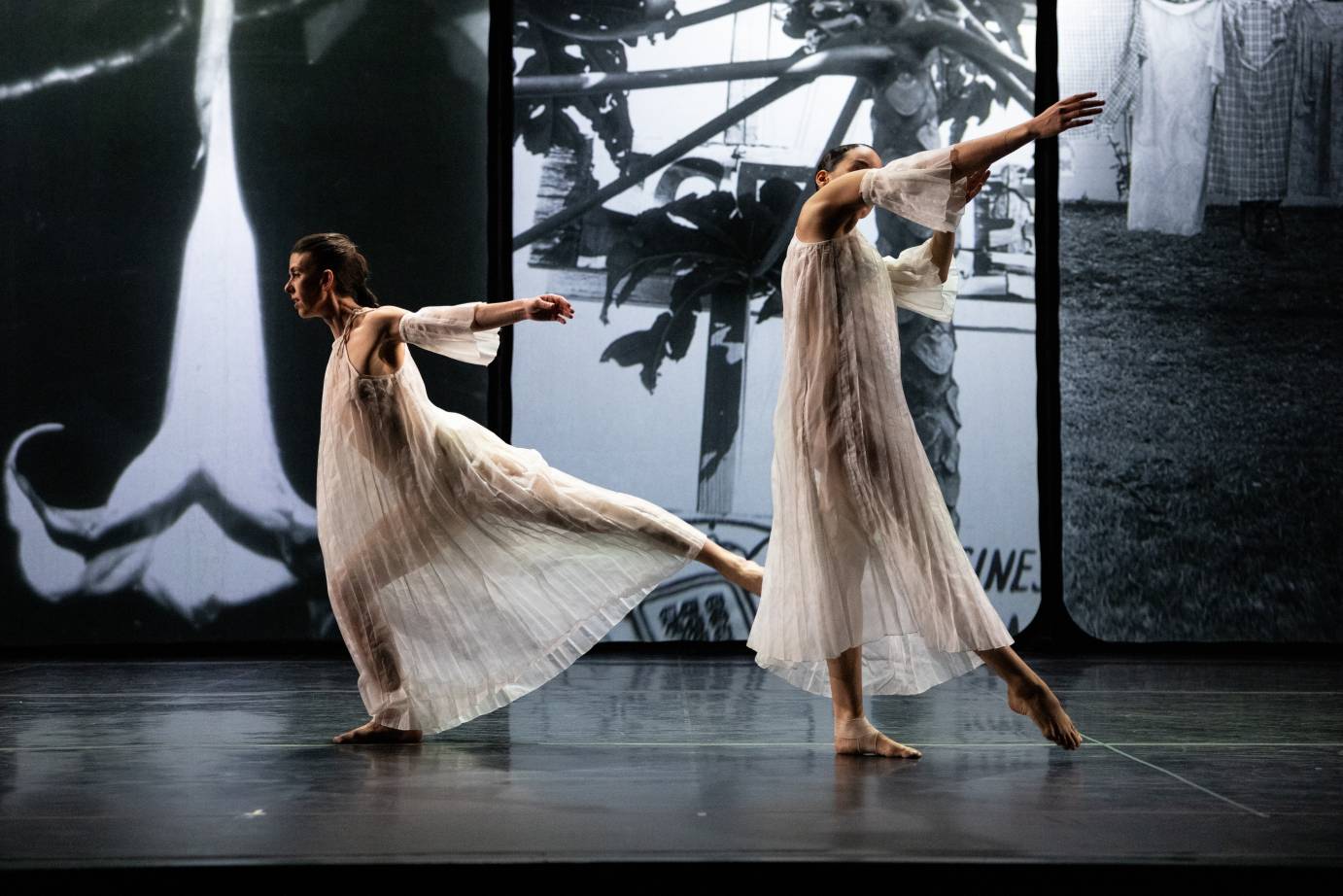

Cows graze, and junked cars rust among the weeds. Sunlight brightens laundry hanging out to dry, and cups of soft-serve ice cream beckon from a drive-in window. These images and hundreds more, captured in black-and-white photographs, parade across the stage courtesy of artist Robert Rauschenberg, who gives the dancers in Trisha Brown’s Glacial Decoy a backyard to romp in as wide as America.

This deeply satisfying revival grounded the Trisha Brown Dance Company’s recent season at The Joyce Theater; but the troupe’s March 26 program also unveiled a wonderful surprise — In the Fall, a stunning new work by French choreographer Noé Soulier. Produced by the Cndc-Angers, with support from Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels, and the Festival d'Automne à Paris, In the Fall received its premiere in France last November. Rounding out the evening, the company scampered through Brown’s Working Title, a playful closer.

Collaborations between choreographers and visual artists often produce works of uncommon depth, as Glacial Decoy (1979) confirms. This postmodern incarnation of the “Americana ballet” is also a masterpiece in the extended Ballets Russes tradition. Brown’s first creation for the proscenium stage prompted her and Rauschenberg to tinker with and overhaul its conventions. They thought up new ways to create a spatial or numerical illusion (a decoy) within its three-walled box.

Instead of portraying infinity with a vanishing point upstage, Rauschenberg suggests unbounded space with his photographic miscellany. Fragmentary views of America move from left to right, and from one illuminated window to the next, offering teasing glimpses of the vast nation outside the frames. From these fragments, we infer the whole. And what of our teeming millions? The human form is absent from the screen, cuing the dancers’ entrance. Brown, too, would like to supply a multitude. If this were old-school theater, she might choreograph a march in which spear-carrying extras quickly circle around backstage and reappear. This being Proscenium 2.0, however, Brown makes four women in filmy robes dart in and out of the wings; while a fifth woman wanders onstage near the end, slyly suggesting that the dancers we see may be stray members of a horde.

Glacial Decoy also reminds us of the passage of time, with its seemingly endless progression of frozen moments advancing at 4-second intervals marked by a mechanical “tic.” The nostalgic quality of these scenes and the relentlessness of their passage point toward eternity, while the dancers’ pleated, white frocks hint at change on a glacial time-scale. This Decoy is both intimate and sublime.

For all that, the dancing is a light-hearted affair. At first, Catherine Kirk and Ashley Merker alternate, teasing us with peekaboo entrances and exits. Loose-jointed and free, these elfin figures trace squiggly gestures, make sudden hops, and prance backward and forward. Merker turns demurely as if tucking something into an invisible belt, and her fists knock together like pendulum balls. Kirk’s raised finger circles in the air. Each has her own phrases to execute, of varying duration, and when they synchronize briefly, on opposite sides of the stage, their unity startles.

Cecily Campbell and Jennifer Payán, by contrast, dance side by side, coming so close that at times they bump into each other. At one point, Campbell falls sloppily against Payán’s back, and they topple forward together. Other sequences are in neat opposition. Brown dials down their speed, and dials it up again. Campbell and Payán slow to a near stop, and then, as if a spell were broken, they suddenly revive and frisk. Similarly, their weight seems to come and go, making them galumph or tread delicately. Balancing, they pause to rearrange themselves.

Gradually, Brown complicates the scene by bringing back Kirk and Merker. Duos become trios, and then four dancers are on stage at once. Things get wild, when Amanda Kmett’Pendry streaks in and out unexpectedly, like a bird blown off course. Then the dance suddenly compresses, with the women circulating in a tight cloverleaf upstage. Calm is restored as the dancers exit, retreating with their lively commotion into an imaginary distance.

Jennifer Payán and Catherine Kirk in "In the Fall." Photo: Maria Baranova

Soulier claims to be more interested in the dancers’ rehearsal practice than in Brown’s vocabulary, and for programming purposes the grounded, sculptural quality of In the Fall makes a lovely contrast with the sprightliness of Glacial Decoy. Brown did not have only one look, of course, and heavy pieces like Newark (Niweweorce) and Twelve Ton Rose might resemble Soulier’s work more closely. In the Fall has its own wonderful style, however, almost overwhelming the viewer with the dancers’ luscious physicality.

At the outset, Burr Johnson and Merker find themselves turned upside down and virtually imbedded in the floor as if they had crash-landed. Gradually their legs reach upward, working against gravity. This slow stretch will become emblematic, as In the Fall explores the art of the développé. Gradually their poses evolve, and even more gradually the dancers re-orient and re-position themselves in space, crossing and aligning. Johnson takes a profile position on one knee, still sunken but aerodynamic. Merker rises, and limbs unfurling she spreads herself wide. Soulier writes of “inorganic transitions,” but, in fact, these serene evolutions suggest the hidden life-force driving biological growth. Though the dancers are solidly planted, we can feel them respire. As Johnson lies curled on his side, his hand rises tendril-like past his face.

Burr Johnson and Ashley Merker in "In the Fall." Photo: Maria Baranova

Having established some themes, Soulier proceeds to enlarge the work. More dancers enter, and they begin gently to make contact, one figure affecting the position of another as it expands. Whether these individuals have the will to manipulate each other, or are acting from unconscious impulses remains a question. Campbell performs a solo of small, tight moves, and her pauses and changes of direction suggest a mix of certainty and indecision. Unexpected events affect the environment. A shaft of sunlight seems to pierce the gloom, and a red glow suffuses the stage. A bell suddenly clangs. When the movement increases speed, the dancers’ neat shapes threaten to break apart. Remarkably, however, their bodies never lose their weight or elasticity. Dressed in primary colors, they have the physical integrity to weather any storm, and are able to stop and begin again. Their sensuous, animal strength is riveting.

Catherine Kirk (in air), Jennifer Payán, Cecily Campbell in "Working Title." Photo: Maria Baranova

Insouciance returns with Working Title, a gay and frolicsome piece with brightly patterned costumes and a score by Peter Zummo, whose music manages to stimulate and feel laid-back at the same time. Swinging and twisting, the dancers burst onto the scene and begin to circulate. They might be guests at a garden party, drifting past or collaring each other, latching on and shoving off. After everyone has had a few, conversations may take an unexpected turn, and you never know whom you’ll run into. Indeed, unpredictable behavior seems to be the norm, though when some of these revelers pass out on the floor, it’s tempting to say, “I told you so.” Others made of sterner stuff manage to remain poised even while teetering off-center. Some run, some crawl. Toward the end, the holdouts perform a series of flamboyant solos, sinking and swiveling, jogging and dodging, and we remember why we come to these parties at Trisha’s — for the sheer pleasure of moving.