IMPRESSIONS: Bill T. Jones' "Memory Piece: Mr. Ailey, Alvin… the un-Ailey" at New York Live Arts

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company

Memory Piece: Mr. Ailey, Alvin… the un-Ailey?

Conceived, written and performed by Bill T. Jones

Lighting design by Robert Wierzel | Sound design by James Bennett | Projection by Janet Wong

Video excerpts from: Revelations: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater | Secret Pastures: Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company | Au Bord du Précipice: Alvin Ailey for the Paris Opera Ballet

Musical excerpts from: My Lover’s Prayer by Otis Redding | The End by The Doors | When the Music’s Over by The Doors

Special thanks to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

May 15 - 24, 2025

Bill T. Jones says he regrets that he did not pursue a friendship with his choreographic elder, the late Alvin Ailey (1931-1989). Yet Ailey’s towering figure cast a shadow across his path, and Jones’s new Memory Piece: Mr. Ailey, Alvin… the un-Ailey, tells the story of a relationship. It feels odd to call this fascinating solo performance a one-man show, though Jones is partnering a ghost.

Created last year for the Edges of Ailey exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and reprised as part of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company’s home season at New York Live Arts, on May 17, Memory Piece is touching and profound. It describes the younger artist’s complicated feelings toward the man who could have been his mentor, if generational differences and Jones’s powerful desire to make his own mark had not gotten in the way. Now, however, Jones has reached an age (73) when he can contemplate Ailey from the heights.

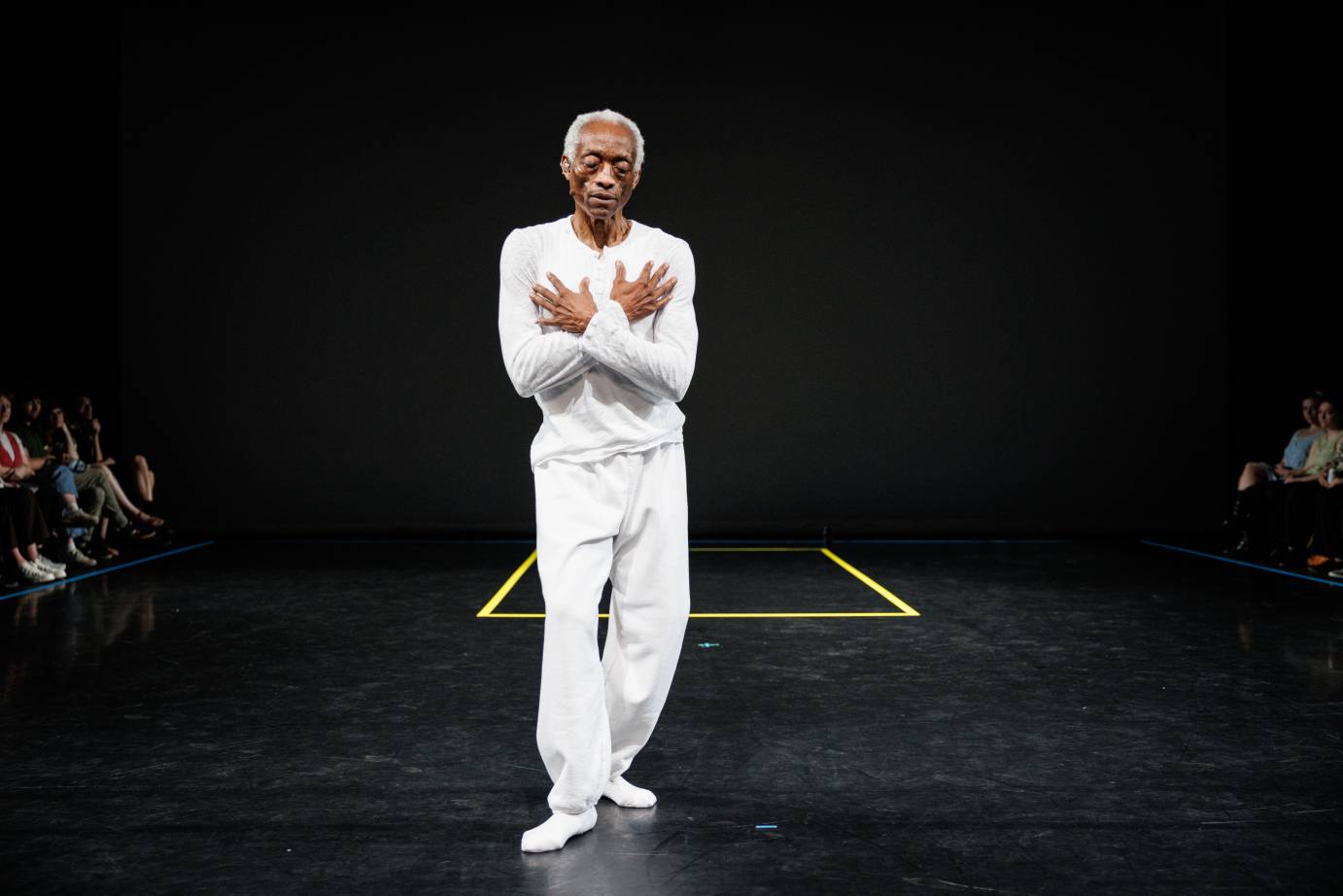

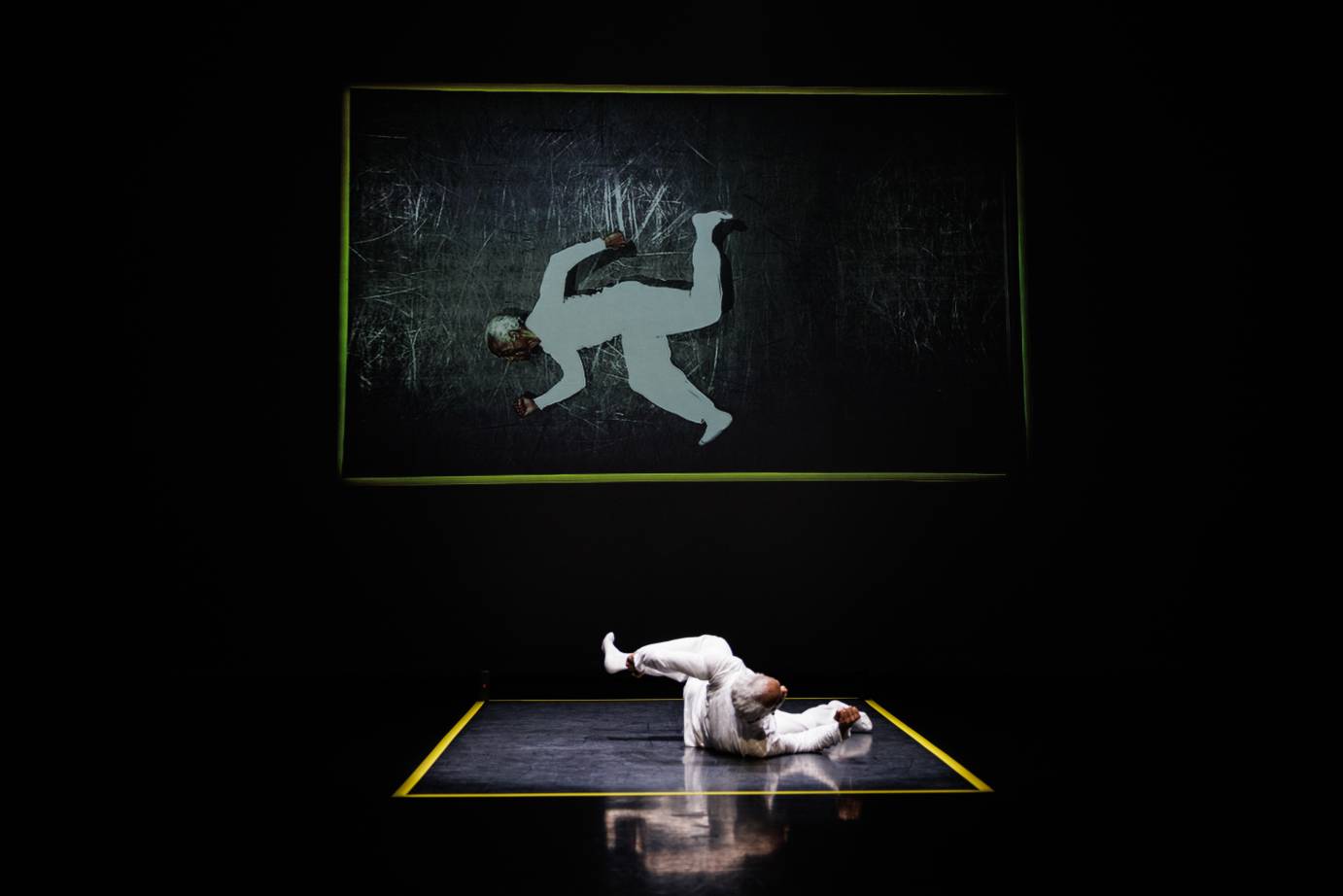

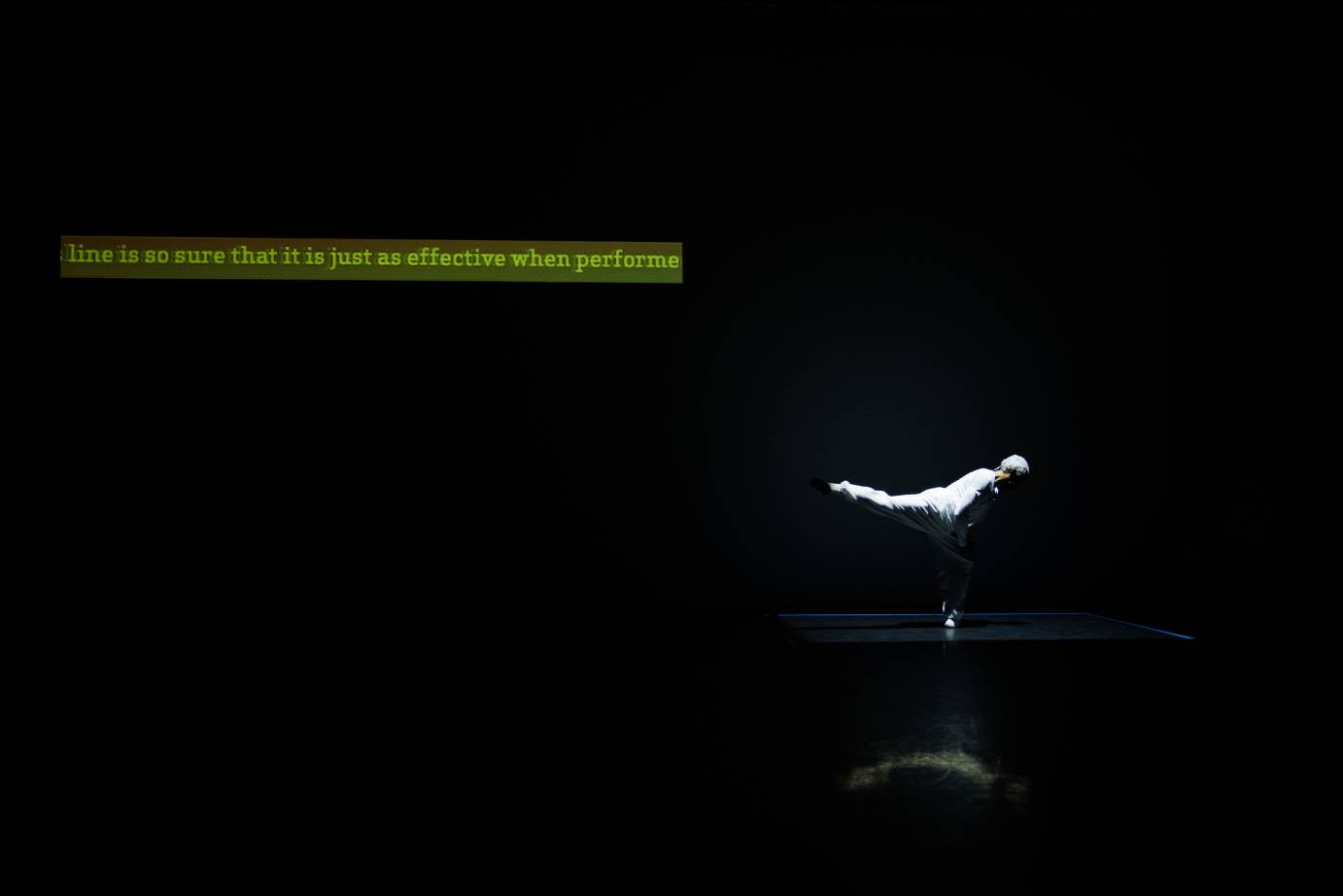

As Jones trundles on arthritic feet around the rectangle at the center of the stage, an early film of Ailey dancing Revelations appears projected on the backdrop, the muscular young hero exuding glorious energy. The men seem to have traded places, with Jones becoming the senior partner. Belatedly (isn’t this always the way?), the barrier between them drops; and Jones allows himself to feel a surge of sympathy and understanding for a man now younger than himself, whose trail-blazing career ended prematurely. Jones does more than call upon Ailey in this dance accessorized with text and images. Telling stories with the skill of a seasoned raconteur, he describes his solo as a “lover’s prayer.”

Making posthumous love to Ailey may be overdoing it; but we sense Jones’s genuine longing for an intimacy that previous circumstances made impossible. What would Ailey think of this profession of love? Perhaps he would note wryly that in Memory Piece Jones has made a work that is still mostly about himself.

As Jones moves, stretching and twisting to the degree his wizened body now allows, sidling with his arms extended for balance, and tossing off cultural references like tendus and jazz hands, he recalls his own trajectory as an artist. His memories, which inevitably are both “vague” and “focused,” do not appear in chronological order. Yet they take us from his childhood, when he spied in wonder on the dancing at a rural nightspot, to his experiences as a college student at SUNY Binghamton, and then to his emergence as a choreographer on New York City’s downtown scene. Quoting dance critic Jennifer Dunning, Memory Piece connects Jones’s childhood vision of “Vess’s Mary” working her pink-sequined behind to the music of B.B. King, with Ailey’s celebration of Black culture in his classic Blues Suite. Here Jones’ eyes light up, and he seems to experience his childhood ecstasy anew.

In college during the 1970s, however, Jones became aware of the challenges confronting Black dancers. Even in modern dance circles, the Black body remained a site of contention. Jones’s white teachers struggled to imagine their Black students fitting in, except, perhaps, at the Martha Graham Dance Company; while Black professionals informed him that the Ailey company was out of reach for all but the most technically accomplished. Despite the Ailey company’s prestige, Jones later discovered, not all Black dancers aspired to join it — for some students, the ultimate goal remained a spot in a ballet company.

Ailey, too, was not above bragging about his work with ballet companies, telling Jones at a 1982 meeting in Los Angeles about his recent experience choreographing for the Paris Opera. Sitting in a darkened hotel room, perhaps to hide his fatigue and the effects of overindulgence, Ailey shared his thoughts about the perils of celebrity. Was he offering Jones the benefit of his wisdom, or was he looking for a friend who would understand him? We now sense his vulnerability, but, at the time, Jones had other concerns.

Ailey always had an eye for the coming thing, however; and the following year Jones encountered him at a showcase, where a jury of venerable figures from the Black dance community convened to inspect the upstarts. With his legendary generosity, Ailey would go on to present Jones’s work insisting that his rigorously trained dancers would improve it — even as he begged Jones not to hurt them. Yet the two choreographers had incompatible visions. In his notebooks, Ailey described himself as a “romantic,” and his musings reveal him thoughtfully analyzing the public’s taste. Jones, however, had inherited a choreographic revolution. The mavericks performing at the Judson Church believed paradoxically that rejecting what the public loved best would make dance more democratic. Calling themselves post-modern, they condemned showmanship and disdained pandering to the crowd.

Jones recalls Ailey saying that he enjoyed watching the experimental artists downtown, “When they dance.” In practice, this meant that Ailey (like his close contemporary Paul Taylor) would quietly absorb the fashion for pedestrian movement, while rescuing modern dance from the nihilism of the avant-garde. This example did not help Jones, however, who had to chart his own, perilous course between the tastes of conservative critics and the pitiless manifestos of radicals intent on dynamiting the past. Arlene Croce and Yvonne Rainer were his Scylla and Charybdis, and in Memory Piece Jones quotes them both. Like others of his generation, he had to shoulder the responsibility of reinventing theatrical dance while maintaining a reputation for edginess. Evidently, this could only happen outside Ailey’s orbit.