Impressions of Abraham.In.Motion's "The Watershed" and "When the Wolves Came In"

The Watershed (full-evening work) and When the Wolves Came In (consisting of When the Wolves Came In, Hallowed, and The Gettin')

Presented by: New York Live Arts, New York, NY

September 24, 2014; 7:30 p.m. and September 27, 2014; 7:30 p.m.

Dancers: Kyle Abraham, Matthew Baker, Winston Dynamite Brown, Tamisha Guy, Catherine Ellis Kirk, Penda N'diaye, Jeremy "Jae" Neal, Jordan Morley, Connie Shiau

Musicians for The Gettin': Robert Glasper Trio (Vicente Archer, Otis Brown III, Robert Glasper) with Charenee Wade

Choreography: Kyle Abraham with Abraham.In.Motion

Live music for The Gettin': composed by Robert Glasper

Recorded music for The Watershed: Barbara Mason; Jimmy Hughes; Otis Redding; Hildur Gudnadottir with BJ Nilsen and Stilluppsteypa; Frederic Chopin; Christopher Tignor; Anonymous; Ryuichi Skamoto; Coplan; Demdike Stare; Giuseppe Verdi

Recorded music for Where the Wolves Came In: Nico Muhly (When the Wolves Came In), Cleo Kennedy and Bertha Gober (Hallowed)

Set design: Glenn Ligon

Costumes: Karen Young (The Gettin', The Watershed), Reid Bartleme (When the Wolves Came In, Hallowed)

Lighting: Dan Scully

Sound design: Sam Crawford

FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF KYLE ABRAHAM

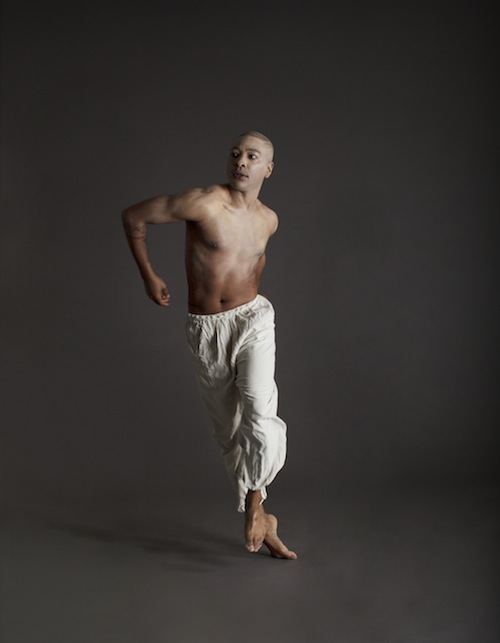

Based on lengthy interviews with him and the experience of some of his art in the theater, one could say that Kyle Abraham is a choreographer in his late 30s who was born and reared in Pittsburgh, who discovered his vocation in dance at the comparatively advanced age of his late teens, and, yet, who had the right physique to pursue his dreams and the luck to find schools and conservatories of international stature to recognize his gifts. One could say that he is a young man lucky in love and in work, albeit with some challenges (a boyfriend on the other side of the country; money woes until recently, when a MacArthur Fellowship provided rescue, yet still only one grant when his peers are getting them yearly; dancer-colleagues who don't honor their commitment to him and move on to greener pastures when Abraham is in the midst of making dances on them, etc.).

One could say that he is practicing his art -- the intellectually provocative, if somewhat recondite, 21st-century art of postmodern dance -- for a small, yet sincerely admiring and emotionally supportive audience base, which includes at least one of his mentor-heroes, the choreographer Bill T. Jones, current artistic director of Manhattan's New York Live Arts and Carla Peterson, its former artistic director, both of whom gave him feedback on his most recent dances during their gestation.

One could also say that Abraham is knowledgeable about jazz and other American music; that he has the rare skill to construct a wordless theatrical scene with a definitive beginning, middle, and end and the imagination to invent surprising and memorable gestures; that he's good-looking and open-hearted and likeable. One could say lots of appreciative things about him. However, in his interviews, such observations are peripheral to Abraham's most important idea of himself, which is that he's a black gay man. The reader is led to understand that Abraham's dances begin in that definition of his identity and, on their most important level, concern that definition of his identity, always with that wording. We are intended to look at his dances through that lens.

Of Race and Suffering--Sights and Sound

He's had time to think about what he wants us to see here. Since 2012, Abraham has been a Resident Commissioned Artist at New York Live Arts, a remarkable perch for a mid-career choreographer, which offers "two years of a full-time salary plus healthcare benefits and a substantial commission for a new work that is produced by and premiered at New York Live Arts." The new work turned into two evenings. One, "The Watershed," is described in "Out" Magazine by Brian Schaefer, one of Abraham's interviewers, as "addressing, in part, the history of race in America." The various discrete sections of this 70-minute Tanz-theater work zigzag from present (biracial couples embracing in public) to remote past (dancers dressed in clothing suggestive of the 19th-century) to an ageless place of suffering (a man's solo to an archival prison song, perhaps one of the songs collected in the late 1940s at the notorious Mississippi hellhole Parchman Farm), to the U.S. of today.

The repertory evening, some 90' long, consists of "When the Wolves Came In," an ominous yet also puzzling work about gender as an artificial (and chosen) construct; "Hallowed," a faceted suite marked by grief and religiosity; and "The Gettin'," which refers directly to Abraham's visit to South Africa and the effect on him of the museum devoted to Hector Pieterson, a 13-year-old fatally shot by white police in Soweto, in 1976, when he participated in a protest by schoolchildren against the government's imposition of English and Afrikaans in the schools as the languages of instruction.

Tying all together is a piece of music from 1960, which I believe we hear a bit of, unannounced, after the second intermission, on a recording by the 1988 MacArthur Fellow, drummer and composer Max Roach. Called "We Insist! Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite," the music on the record was written to commemorate the centenary of Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation; Abraham heard the recording and began to think about aspects of the 1960s Civil Rights movement. (A portion of Roach's composition, written with Oscar Brown Jr., was intended to be an improvisatory ballet.)

I don't understand the suite's connection to many of the recorded arias and songs (or songs without words), from Verdi and Chopin to Otis Redding and Demdike Stare, which make up the anthology score for The Watershed; however, I can certainly hear its links to Robert Glasper's reverent homage to Roach, played by the composer's trio live for The Gettin', to the recordings of gospel star Cleo Kennedy and SNCC Freedom singer Bertha Gober for Hallowed, and to the massed choral music of Nico Muhly for When the Wolves Came In. The mingling of rage and melancholy in "We Insist!" seems also to have influenced the set designs of Glenn Ligon: for The Watershed (an onstage "tree," constructed from piping, and relevant projected images, still and moving) and for all the sections of the Wolves suite (more projected still and moving images, many of black individuals suffering from white violence).

GETTING WITH THE PROGRAM

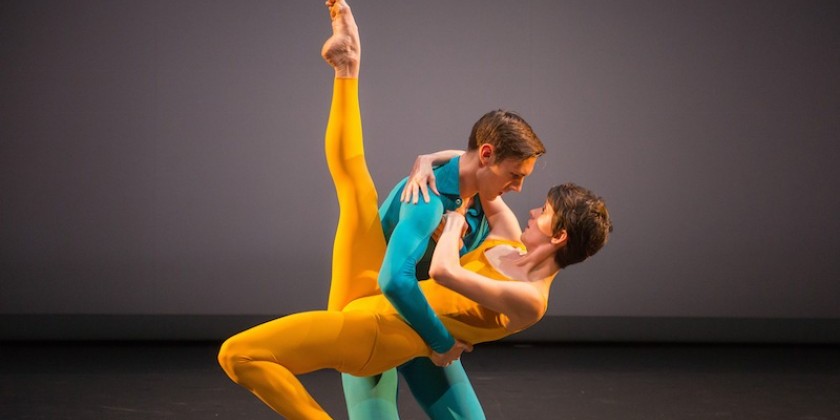

And so, over the two evenings of Abraham's most recent group works, presented at New York Live Arts last month, this old, straight Jewess attempted to get with the program. In the opening scene of the evening-length suite, The Watershed, I diligently labored to scrape off any shred of Romanticism clinging to the way I processed the male-female duets. In The Gettin' -- the work in the repertory evening explicitly based on Abraham's personal reflections about Apartheid as well as on "Tears for Johannesburg," the last track of the "We Insist!" album, Roach's response to the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre-- I dutifully tried to figure out when the Abraham.In.Motion company's two Caucasian men represented aggressors and when they were meant to be understood as sympathizers with the rest of the group, all dancers of color. (This was rather a tiring exercise.)

In When the Wolves Came In, the title work on the repertory program, I put the lid on my curiosity about why no one had thought to darken the pale color of the underpants for one of the men, which, whenever he turned upstage, showed a large wet spot of what was surely sweat where the cleavage of his buttocks was. Since this work, costumed by the smart and experienced dance designer Reid Bartleme, also featured disfiguring beehive wigs for the women and a cartoonish platinum wig for the dark-skinned underpants guy, I decided that we were supposed to notice the embarrassing wet spot, which led me to presume that humiliation is one of the themes of Wolves. Was I right to presume this?

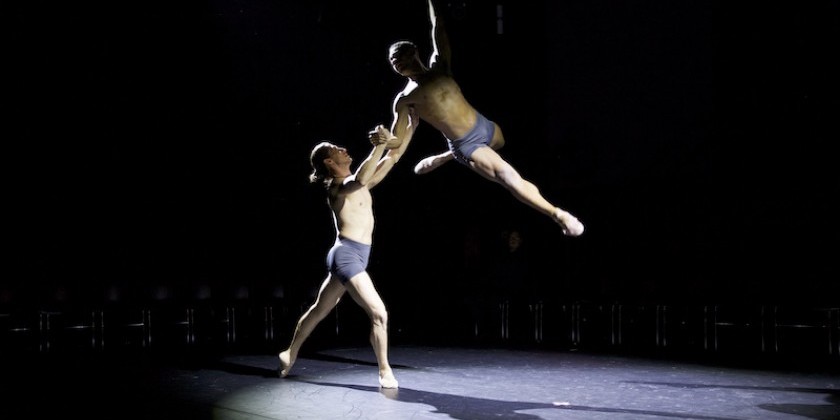

During the repertory evening, Abraham set a man's solo -- a dance marked by outbursts of spread-eagled limbs and arrowing excursions into space, which alternated, at unpredictable intervals, with stony stillnesses -- to the Roach-Brown "Driva Man," a work song, in a blues format, invoking slavery's backbreaking and mind-numbing picking of cotton, from sun-up to sundown, under the goading of an overseer. Sung with dignity and wonderful clarity of diction by Charenee Wade--who, like the original "We Insist!" singer Abbey Lincoln, accompanied herself austerely on a tambourine--the lyrics include the refrain, "Ain't but two things on my mind / Driva Man and quittin' time." The song is stately and grounded, parcelling out the narrator's energy to preserve his stamina to get through the job, whose cruelly repetitive rhythms are embodied in each line. Meanwhile, the dancing -- now hectic, now frozen -- seems to spurt from a disoriented, if spectacular, panic that no cotton-picker would be able to sustain in the field for even ten minutes.

In other words, we're not seeing a staging of the song but rather of Abraham's emotion in the presence of the song. We're not being given a taste of a horror directly, figuratively, through an artist's imagination of what it was like, which is what Roach and Brown tried for, but rather an image of how one of our own contemporaries literally responds today to the Roach-and-Brown imagining of what that horror was.

I did learn some things by trying to look at the dancers through Abraham's prism. One lesson is that I had increasing difficulty focusing on what I was supposed to think the more absorbing I found what I was watching. The more arresting the material was, whether a projected, repeating film loop of a police officer beating a supine woman on a crowded highway; or a loping phrase of beautiful Tamisha Guy's gemsbok leaps; or an archival recording of a singer -- surely long dead by now -- scratching at the extremity of pain during a religious service, the more of a chore it became to slap my concentration into the proper interpretation: "This isn't supposed to be arresting for its own sake," I kept reminding myself, "and it's not providing a platform for you to connect to it from your personal experience; this is how Kyle Abraham feels."

Eventually, that shackling of perception led to an epiphany, in the sense of "This is a glimpse, an analogy for you as a member of the audience, of what it means not to be free, in this case, not free to perceive and interpret the world on your own for 90 minutes." Now, one could say that the epiphany could have made its point, at least intellectually, in a shorter time. But the standing ovations for both programs suggested that a significant portion of Abraham's audience is open to experiencing fully how he himself meets life, both on the street and in his head, no matter how long it takes.

A question I'm left with, though, is, "Am I, old straight Jewess that I am, open to repeating this experience the next time with Kyle Abraham's choreography?" If I weren't reviewing it, would I chose to attend a future Abraham performance and pay full price for a ticket? Yes, I'd seek another program of his works, and I'd pony up full price. He has gifts. However, the next time, I'd give myself the freedom to think what actually occurs to me as those gifts are unfurled in the persons of his well-trained and, in some cases, deeply committed dancers (whom Abraham credits as his collaborating choreographers). And if they aren't theatrically absorbing, for their own sakes, I'll give myself the freedom to leave.