Impressions (The Dance Enthusiast's Brand of Review) of Merce Cunningham: Early Works

At Baryshnikov Arts Center

May 19, 2016 at 7 p.m.

Cunningham Ballett (1958 film of Changeling, Duet from Suite for Two, and Duet from Springweather and People)

Changeling (1957, NYC premiere of 2015 reconstruction)

Choreography: Merce Cunningham

Dancers: Merce Cunningham and Carolyn Brown (film), Silas Riener (Changeling reconstruction), Vanessa Knouse and Benny Olk (Suite for Two)

Musicians: John Cage and David Tudor (film), Stephen Drury (live)

Speakers: Patricia Lent, Christian Wolff

Musical scores: Christian Wolff (“Suite” for Changeling), John Cage (“Music for Piano” for Suite for Two), Earle Brown (“Indices” for Springweather and People)

Choreographic staging: Jean Freebury and Silas Riener (Changeling reconstruction), Andrea Weber (Suite for Two)

Costume Designs: Robert Rauschenberg (for Changeling and Suite for Two) and Remy Charlip (for the “tie-dyed off-shoulder ruffle duet” in Springweather and People)

Costume Reconstruction for Changeling: Jeffrey Wirsing / Lighting Design: After the design by Beverly Emmons for Suite for Five

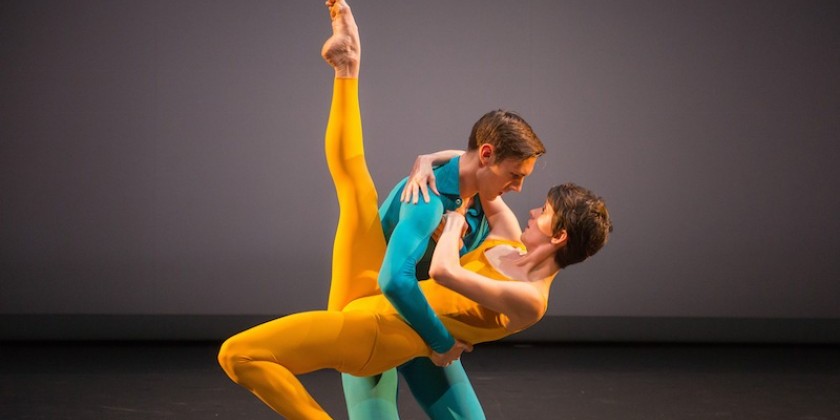

Pictured above: Vanessa Knouse and Benny Olk in Merce Cunningham's Suite for Two

Merce Cunningham's little 1958 masterpiece Suite for Two — an intensely romantic duet for the minds and bodies of an International Modernist-era couple whose faces project the reserve of two Buckingham Palace Grenadier guards changing shifts — has never been retired from the Cunningham repertory, which is why there's no “reconstruction” credit for it here. Formally, it belongs to a larger work, Suite for Five, but the duet was performed independently, as well, by Cunningham and Brown, its original cast, and it continues to be programmed that way sometimes.

I first saw this current staging of the duet, by Andrea Weber (an unruffled flying stork of a dancer in Cunningham's company during his last years), this past December. It was programmed on an anthology evening of modern dance, hosted by the American Dance Guild, where the choreography was embodied by Vanessa Knouse and Benny Olt, the same dancers who performed it at the Baryshnikov Arts Center (BAC). Their long-boned physical elegance and kinesthetic agility were matched by their particular performing intensity (she was the alpha of the pair, a reverse of the dynamic with Brown and Cunningham), and, from their meticulous dancing, it was clear that we were watching choreographic art of a very rarefied achievement. How great is that: A modern dance that retains its heat after nearly six decades!!

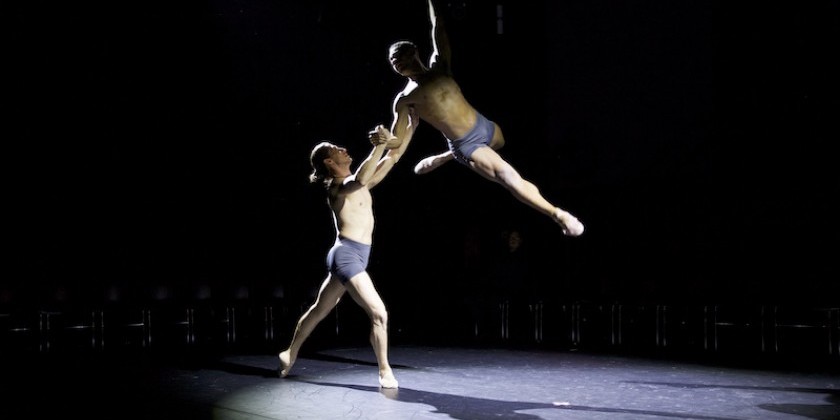

From the astonishing first stage moment — a lift in which the woman seems to have glided, full body, onto the man's shoulder and momentarily perched there — the audience is brought into a world of the imagination, where the natural world has been recreated through vision and discipline by entirely artificial means. This is one of what I think of as Cunningham's “still point” works (from T.S. Eliot's Burnt Norton: “At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless; / Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is. . . Except for the point, the still point / There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.”). Or, as the original program note for Suite for Five reads: “The events and sounds of this ballet revolve around a quiet center, which though silent and unmoving, is the source from which they happen.”

The use of the word “ballet” in the note is important. Suite for Two (and, I presume, the full Suite for Five), is a work for classically trained executants: Although the dancers' feet are bare and their many lifts are magnetically idiosyncratic in the surprise of their doing, as well as in the forms of their sculpture, the movements are turned out, both physically and temperamentally; feet are pointed; spines are carried so that the skeleton is placed to carry the weight of the body in a plumb line; the deportment of arms and hands inevitably resolves into aspects of Euclidean geometry, even when the gestures depart from the danse d'école; and the dance maintains an ongoing forward motion in time, dotted by pauses after especially demanding sequences.

The score “Music for Piano,” by John Cage — a not unfriendly yet curious soundscape of notes (delicate and/or thumping, according to choices made by the instrumentalist), emanating from a piano without obvious relationship to harmonic, tonal, or serial organizations of any type — was played at BAC by Stephen Drury. Introducing Knouse and Olk's performance, the composer Christian Wolff explained that both the music and the choreography for Suite for Five (and, so, for Suite for Two) had evolved from compositional processes that were based, in part, on the distribution of imperfections in sheets of paper and on chance operations. Most audience members today can appreciate, however, that, although Cage's sonic productions in musical venues often depart radically in effect from what is commonly thought of as “music,” the same is not true for Cunningham's dances, which are structured according to the same kinds of happenstance and chance procedures.

In the 21st century, if you didn't know that Cunningham used iconoclastic methods of structuring movement, you might think him a little odd but you wouldn't be likely to question the relationship of his dancers to rigorous training, these days, to rigorous classical training. (His 20th-century audiences had to work harder to get to this appreciation.) Suite for Two is a duet, even debatably a pas de deux, for a heterosexual couple whose movement brings them into considerable physical intimacy while maintaining a reserve, a distancing, in their mutual social recognition. They rarely face one another, and they hardly ever maintain more than passing eye contact, even though her lower spine is about to be fitted, imagistically speaking, into his lower torso. The high-art severance of physicality and emotion, of sensuousness or sensuality and conscious recognition, is still sexy-cool, even today; and the fact that, at this point in cultural history, popular music has pretty much caught up with Cage's four-way openness to sound for its own sake has educated the current generations of audience members to accept what they hear as well as what they visually take in.

Changeling, the 1957 solo that Cunningham made for himself, to a score by Christian Wolff entitled “Suite,” did go out of repertory and was thought lost for half a century. The current reconstruction — by erstwhile Cunningham company members Jean Freebury and Silas Riener — is based upon a recently discovered 1958, black-and-white film, for German television, that was made of Cunningham performing the dance. The reconstruction of the costume, of a brick-colored shirt in fanciful tatters and matching tights and cap, was possible because the original costume had been saved and is now, with the rest of the Cunningham company's costumes, sets, and designs, held in perpetuity by the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis.

In her absorbing memoir Chance and Circumstance, Carolyn Brown writes how Cunningham spoke of himself personally as a “changeling,” given that he sprang up as a choreographer in a family of lawyers and other practical folk, and the solo — fiendishly difficult in its technical and kinetic demands, in the exactitude of its wit — suggests a fantasy creature, an overgrown leprechaun, with a physicality both human and avian. The spine is held in a variety of stances, straight and curving; there are separately coordinated yet simultaneous movements for the head, torso, arms, and legs; much of the movement either turns inward or ties the dancer into knots, thereby suggesting knotty reflections. One jaw dropping transition has the soloist, lying on the floor in a ball, suddenly jackknife his own body back and forth, with barely any light between him and the stage floor, like a croquet ball going back and forth through a wicket. Riener, a dancer of truly virtuosic and excitingly dramatic ability, turned in a fine account of Changeling, but it looked like an impersonation of Cunningham's film performance rather than a dance that the dancer had made his own.

Following an introduction by Patricia Lent, Director of Licensing for The Merce Cunningham Trust, the BAC evening opened with the 24-minute film, Ballett, made for German television; its rediscovery, by the filmmaker Alla Kovgan, was the program's reason for being. In the film, the musical scores are played on the piano simultaneously with the dancing; the pianists were composers Cage (sometimes employing mallets or otherwise bullying the piano) and David Tudor, and the dance performances comprise not only Cunningham in his startling and deeply personal account of Changeling but also Cunningham and Brown in two other early Cunningham duets — Suite for Two (also performed at BAC live) and Springweather and People. In all, these aesthetic experiences are so profound in their entwining of technical prowess and emotional texture that I, for one, would nominate this as among the greatest dance films ever made. The choreography, with its combinations of unforeseen invention and sly theme-and-variation moments is staggeringly great. The performances are convincingly those of gods. The lighting, including the lighting of the musicians and the piano, is a musical expression in itself. Sometimes, there are long takes without edits, in the Fred Astaire manner. (Cunningham was himself an Astaire fan.) The framing and timing of the occasional close-ups intensify the emotive character of the dance, and, in the case of those for Brown, provide one most wonderful chronicle of a woman's expressive beauty as a stage creature being in the moment in the course of her dancing. I wish we could have seen the color versions of Remy Charlip's costumes for Springweather and People, but that's for the next life. For this one, bravi to the filmmakers, directed by Herbert Junkers.

Share Your Audience Review. Your Words Are Valuable to Dance.

Are you going to see this show, or have you seen it? Share "your" review here on The Dance Enthusiast. Your words are valuable. They help artists, educate audiences, and support the dance field in general. There is no need to be a professional critic. Just click through to our Audience Review Section and you will have the option to write free-form, or answer our helpful Enthusiast Review Questionnaire, or if you feel creative, even write a haiku review. So join the conversation.