DAY IN THE LIFE OF DANCE: Bronislava Nijinska's "Les Noces" with Ballet West at The Guggenheim

LES NOCES AT THE GUGGENHEIM

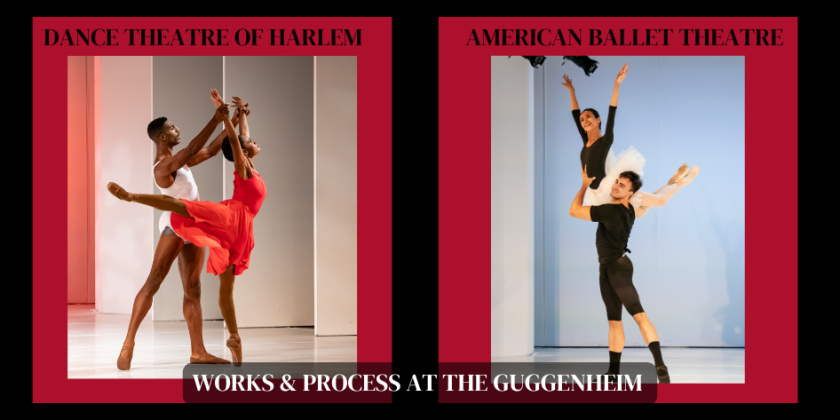

Works & Process presents Ballet West in Les Noces, by Bronislava Nijinska

Panelists: Lynn Garafola, Linda Murray, and Adam Sklute

Dancers: Dominic Ballard, Jazz Khai Bynum, Jenna Rae Herrera, Vinicius Lima, Victoria Vassos, Jordan Veit, and Jane Wood

Sunday, March 26, at 3 p.m., in the Peter B. Lewis Theater

Any ballet preserved in all its freshness for a hundred years is clearly exceptional, defying the fragility that condemns most dances to oblivion. Yet Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces (The Wedding), which was the subject of a Works & Process symposium at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum on March 26, is that rarity and more.

Les Noces, a highly stylized, modernist depiction of the events surrounding a Russian peasant wedding, received its premiere on June 13, 1923, at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique, in Paris, presented by the Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev. That company is long gone, but, miraculously, the ballet remains intact. Imitated, but never equaled, Nijinska’s creation is among the greatest masterpieces of modern art — the Guernica of dance. Ballet West will celebrate its 100th anniversary with performances accompanied by live music at the Janet Quinney Lawson Capitol Theatre, in Salt Lake City from April 14 to 22, 2023.

Any day at the Guggenheim, visitors can stroll through galleries lined with works by Nijinska’s contemporaries, startling, abstract paintings by Vasily Kandinsky, Robert Delaunay, and Kazimir Malevich. Easier to preserve than dances, these pictures open windows onto the fecund landscape of early 20th-century art. Yet nothing can compare with the immersive experience of a living art work. Even at a symposium offering mere snatches of choreography, Les Noces brings to life the heyday of the Russian avant-garde. More than simply a ballet, Les Noces is total theater co-created by Nijinska and two brilliant collaborators, composer Igor Stravinsky and the easel painter Natalia Goncharova, who designed the scenery and costumes. Diaghilev had assembled a team of visionaries. The energy of the dancers’ leaping bodies, the clangor of the music with its chanting, whooping chorus, the ballet’s massive, rhythmic architecture, and its intensely colored atmosphere fuse together overwhelming the spectator.

Nijinska carefully recorded the choreography for Les Noces in her own notations, as she did for her Boléro; and she supervised a major revival for Britain’s Royal Ballet. Yet Les Noces owes its survival largely to the choreographer’s daughter, Irina, who, beginning in the mid-1970s, spent nearly 20 years tirelessly mounting her mother’s ballets around the world. Adam Sklute, the artistic director of Ballet West, is a veteran of productions Irina and her assistants staged for Oakland Ballet and the Joffrey Ballet. Joining him on Sunday’s panel were dance historian Lynn Garafola, who has written a biography of Nijinska, and moderator Linda Murray, curator of the New York Public Library’s dance division.

Sklute emphasized the challenges of staging the work, which in addition to a large corps of dancers employs a massive chorus, with four vocal soloists and four grand pianos in the pit. The musical and choreographic scores do not maintain a steady rhythm, but require the dancers to count in irregular units of 5, 6, and 7. A handful of Ballet West dancers were on hand to demonstrate details, including the curling of the dancers’ hands, doll-like and poignant; and their tricky pas de bourrée, alternately parallel and turned-out, which Sklute suggests are modeled on the dance of the Ballerina doll in Petrouchka.

Films of the Joffrey Ballet and Juilliard School productions, along with slide projections, provided context. The symposium led us in succession through the ballet’s four sections, called Tableaux, which describe in abstract terms the ritual braiding of the Bride’s hair by her companions; the blessing of the Groom; the Bride’s departure from her childhood home; and the raucous Wedding Feast, during which the Bride and Groom are put to bed and the male and female corps mesh spectacularly.

Les Noces has a complicated history. Its gestation was protracted as Stravinsky experimented with various orchestrations (one including player pianos), and Goncharova reworked her designs. Nijinska was a latecomer to the project, but she had her own, powerful vision, spare and abstract, which placed her at loggerheads with the rest of the creative team. According to Garafola, Diaghilev refused to accommodate Nijinska, threatening to replace her, until he saw the touring company of Vsevolod Meyerhold, which brought the brilliant producer up-to-date.

In reality, however, Nijinska’s quarrel was not with Diaghilev, but with Stravinsky, who had his own, whimsical ideas about the work’s mise-en-scène. Stravinsky’s plans, outlined in his autobiography, would have required dancers wearing bright, folkloristic costumes to share the stage with musicians in evening dress, creating “a divertissement of the masquerade type.” Thus, one of Goncharova’s set designs, projected at the symposium, shows a piano standing on stage. This arrangement would never be realized.

While the masquerade was a recurring theme of the Ballets Russes, to which Stravinsky had recently contributed the ballets Pulcinella and Le Renard, he also composed Les Noces (and assembled its fractured text) under the influence of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, with its stream-of-consciousness narrative. Stravinsky’s vision of a humorous masquerade juxtaposing sober musicians and wildly costumed dancers reflected then newly popular theories about a split between the conscious and unconscious mind. The defeat of Stravinsky’s proposal, and Goncharova’s subsequent radical rethinking of her designs, are what allow us to credit Nijinska with the ballet’s ultimate form. “Les Noces was the only ballet in which he [Diaghilev] allowed the choreographer to have a deciding influence over the entire production,” Nijinska claimed.

That production, thanks to her, is infused with the philosophy of abstraction that Kandinsky propounded in his seminal treatise On the Spiritual in Art. The giveaway is Nijinska’s explanation, in a 1963 interview, that she wished “to express the mystery felt by a boy and girl on their wedding day.” Thus, the imposing triangular formations in the choreography of Les Noces represent “spiritual striving.” This remark points directly to Kandinsky, as does the innovative presence in the ballet of abstracted actions and objects—the “braiding” of the Bride’s hair; the “sobbing” of her companions; the “cart” that takes her from her home; and the “cathedral” of the ballet’s final grouping---all reflect Kandinsky’s dictum that physical objects can be “replaced by purely abstract forms, or by corporeal forms that have been completely abstracted.” Nijinska’s theory of movement, developed during her Soviet period, also reveals her devotion to abstract principles.

In the final version of Les Noces, Goncharova’s abandonment of heavily ornamented, primitivist decors in favor of broad planes of color, naked in their simplicity, cannot help but recall Kandinsky, who also wrote, “color is a means of exerting direct influence on the soul.” In Goncharova’s own words, “colors have a strange, magic quality,” and her final designs were inspired by her memories and emotional associations with color---pale ash blue, for serenity and hope; gray, the color of ashes and the past; yellow ochre, suggesting anxiety and suspicion in the midst of the wedding feast; with a brown frame recalling the earth.

Can we put to rest, at last, the queer notion, advanced by Garafola, that Les Noces is a neo-classical work? Nijinska was, in fact, a pioneer of neo-classicism, as can be seen in her ballets Les Biches, Le Baiser de la Fée, and Chopin Concerto. She was also an eclectic genius capable of working in any number of styles. Les Noces, despite the use of pointe shoes (stabbing and decidedly unlyrical) is self-evidently Expressionist, reflecting, in dance, the aesthetics of the Blaue Reiter movement. Ultimately, it is the spiritual content that matters.

In her posthumously published memoir of the ballet’s creation, the choreographer does not speak of her devotion to classical forms but of the importance to her of expressing the “feelings” of the Bride and Groom, whom she viewed as the prisoners of tradition. In fact, with her depiction of the Bride and Groom as nearly static figures, Nijinska anticipates the tension between the individual and society in American modern dance, prefiguring such works as Martha Graham’s Heretic (1929), and even Ohad Naharin’s celebrated dance to the Passover song Echad Mi Yodea (1998). Clearly, Nijinska was aware of the social criticism implied by the “Danse sacrale (L’Élue)” in her brother, Vaslav Nijinsky’s, controversial masterpiece, Le Sacre du Printemps. In Les Noces, Nijinska felt particular sympathy for the Bride, giving the ballet a feminist angle. While Stravinsky’s score features the keening of both mothers, Nijinska’s choreography shows us only the Bride’s mother, who performs a solo of stylized lamentation.

Any chance to see Nijinska’s Les Noces, even in truncated form, is to be welcomed. Kudos to the organizers of the Works & Process series for making it happen. They could not hope to find an extant ballet more compatible with the Guggenheim’s permanent collection.