Day in the Life of Dance- Robert Swinston Brings Merce Cunningham Back to The Joyce

As Compagnie CNDC-Angers Prepares to perform a Cunningham "Event"

Performances: March 10-15, 2015

For tickets go to The Joyce

Three years following the dissolution of the world renowned Merce Cunningham Dance Company, keeping the late choreographer’s masterpieces in the public eye continues to present a challenge.

Though the closure of the company was planned, “It was never part of the conversation that the work not be done, or seen,” says Robert Swinston. The choreographer’s long-time assistant is recalling the deliberations that led to adoption of the “Legacy Plan” announced shortly before the 90-year-old choreographer’s death in 2009. According to this controversial arrangement, the company would be liquidated but the Merce Cunningham Trust would survive to license Cunningham’s dances.

.jpg)

Determined to keep the master’s works alive, Swinston, who now directs a dance center in France, will bring a small group to the Joyce Theater for five nights, beginning Tuesday, to perform a 70-minute, Cunningham “Event” that he has prepared by combining excerpts from the repertory. While these ambitious performances will feature a setting by painter Jackie Matisse, and music by composers John King and Gelsey Bell, it seems fair to say that this presentation by eight French dancers will not be on the scale that characterized the grands soirées of the past, with premieres and performances of complete works at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Even more humbly, on Tuesday, a group of students from the University of North Carolina School of the Arts will present a studio showing of Cunningham’s 1975 piece Sounddance at City Center, staged by Meg Harper and Andrea Weber. Training new dancers in Cunningham’s style, and gradually increasing the opportunities for them to perform is now his mission, Swinston says. But the future seems shrouded in uncertainty.

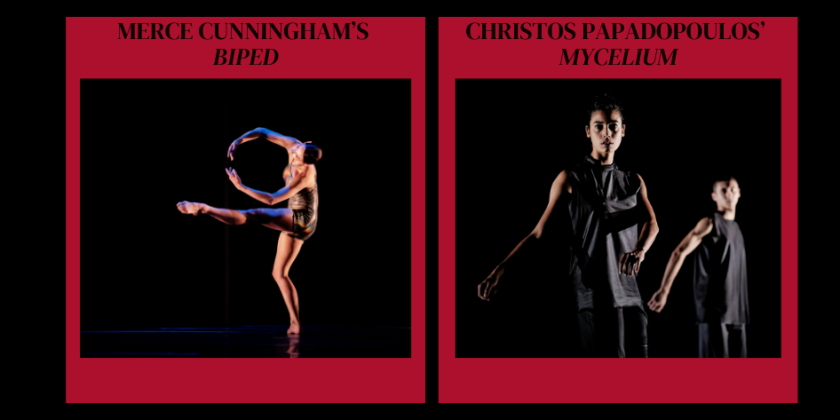

The Merce Cunningham Dance Company disbanded after a valedictory performance at the Park Avenue Armory, in New York, on New Year’s Eve, 2011. That night the dancers passed into history, vanishing into the crevasses of a vast, black canyon. Daniel Arsham designed this awe-inspiring setting, which suggested the valley of death. With dancers performing simultaneously on three platforms in the middle of the canyon, while “molecular” cloud sculptures floated overhead and a team of contemporary composers sounded a fanfare from on-high, the company’s stunning final performance capped an enterprise that had become ever more elaborate—and expensive—in the decades leading up to Cunningham’s demise. Hailed as a leader of the American avant-garde, the choreographer was able to couch his dances in fantastic decors by the likes of Benedetta Tagliabue (Nearly 90), Charles Long (Way Station) and Shelley Eshkar and Paul Kaiser (BIPED). He was able to commission haute-couture costumes (Scenario); with music played by rock stars (Split Sides) or overheard on iPods distributed to the audience (Eyespace).

.jpg)

Swinston was lucky, however. The month before the company succumbed, a friend introduced him to Claire Rousier, the “directrice adjointe” or executive director of the CNDC (“Centre National de Danse Contemporaine”) in Angers. The CNDC-Angers, part of a network of such centers in France, was looking for an artistic director; and Rousier helped Swinston apply for the position. He had a distinguished predecessor. American choreographer Alwin Nikolais had been the first to direct the center in 1978. Though Nikolais only stayed three years, it seems he had chosen this spot carefully. When Swinston’s application was approved by the French Ministry of Culture, he landed in an area of the Loire Valley dotted with fairytale castles, lush with pear trees and flowing with Anjou wine. The local motto, according to Swinston, is “très douce,” which might be translated as “life is sweet.”

From the perspective of American artists, forced to scrounge for their livelihood, the sweetest part may be the CNDC-Angers’ government subsidy. The French honor their “patrimoine,” or cultural heritage. “It’s 100 percent supported by the government,” Swinston says. In Angers, he commands a staff of 16 people in an institution with nine studios and two theaters. The center has its own school, with a two-year program leading to a degree called the “Diplôme National Supérieur” in dance; and students may also receive the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree from the University of Angers. The program, which is free to enrollees, teaches choreography by a variety of modern masters, plus Gaga technique. The object is to give students a technical base from which to pursue their own movement investigations and original choreography. In addition, the CNDC hosts a presenting series (Angers has “a great dance audience,” Swinston says), and engages in educational outreach.

.jpg)

Since arriving in France, Swinston has also begun to make his own dances. “I’m allowed to be a choreographer now, so I’m getting to dream,” he says.

Yet there is, of course, a catch. The CNDC does not support a full-time, resident dance company. Speaking of his dancers, Swinston explains, “They come to Angers when I put them under contract. And when I don’t have them under contract, they’re dancing with other people or doing other things, and they live in different parts of the country.” He says the situation recalls his own experience in New York, in 1980, the year he joined the Cunningham company, when the dancers would be laid off for months at a time.

His immediate goal, he says, is to create an environment that supports his recruits and helps them to grow. “The dancers come up to the level of the choreography, and the choreography makes them better dancers,” he says. “So it is a process….and through that process you develop not only the physical coordination, but you develop the inner strength that’s necessary in order to do this kind of work.”

He has begun by teaching them choreography that Cunningham created before he began to experiment with the Life Forms computer program. “I selected the time period before the computer, because the language was a little bit more direct,” Swinston says. “I thought there were a number of fundamentals that I had to instill in them, and the earlier work had more directness, and revealed more of their personalities at the same time.” The members of the CNDC group come from diverse backgrounds, including at least one hip-hop artist, and Swinston adds that he did not select the dancers only for their appearance or prior experience but also for their presence. “What I want to transmit is the essential part of Cunningham, which is his humanity. For me, that’s very important.”

.jpg)

Assembling an “Event” inevitably demands compromises, but Cunningham himself championed this approach in the multi-directional works that he began to arrange in 1964 for performances in unconventional venues like museums. The upcoming Joyce Theater “Event,” for instance, will include material from the 1976 piece Squaregame, originally made for 13 dancers. Yet the CNDC ensemble only has four men and four women. “I made it like a suite. I made an adaptation, or an abridgement,” Swinston says. “I did this many times, while I was the assistant to the choreographer, in Merce Cunningham’s presence, with the RUGS [Repertory Understudy Group]. I did it for years, making suites or abridgements of full-company dances for four dancers.

“With Merce, when I was working with him, we were always very practical about these matters,” Swinston continues. “The idea was to transmit the material. So we found a way to bring the material back to life, so to speak. That was the whole idea of having what we called a ‘living archive.’”

At the Joyce, in addition to Squaregame, audiences will see portions of Cunningham’s Points in Space; Variations V; Rebus; Fractions and more. “I’ve added a number of things that people have not seen for a long time,” Swinston says. “It’s going to be much longer than what we did here originally, with different materials that people have not seen unless they’re very old.”

.jpg)

Next year, the director plans to revive Cunningham’s Place and How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run, which won Swinston a Bessie Award in 2003, after he first revived it. He hints that eventually he would like to direct a full-time company, but time is not necessarily on his side. His contract with the CNDC comes up for renewal after four years, and can only be extended for a maximum of 10 years. He is now 64 years old.

During his lifetime, Cunningham choreographed more than 200 dances, not counting “Events.” If it were not evident before, then by now it should be clear that a repertory of this size and stature is not well served by a “Legacy Plan” that only provides for occasional, piecemeal revivals; and that does not look beyond the current generation of Cunningham experts. Robert Swinston, and the other individuals with first-hand knowledge of Cunningham’s aesthetic, will not be around forever. When the last one of Cunningham’s dancers has left the scene, who will supervise stagings of these works? Only a company like a “living archive” can guarantee the continuity of Cunningham’s art, and the integrity of our dance inheritance as a whole.

“All I can say about it is that the choreography speaks,” Swinston says praising Cunningham’s brilliance. “Now I’m trying to find my own voice, and make my own dances, but I still am involved with his repertory. I study his work. I study his notes in order to make these reconstructions. And I have to say that I am constantly astounded. I am constantly surprised. I am constantly in awe. And I believe the audience needs to see those things again.”