MOVING VISIONS: Can Dancing Raise Climate Consciousness?

Focus On: Edissa Weeks, Jody Sperling, Jennifer Monson, Jill Sigman, Davalois Fearon, Lynn Neumann, Carolyn Hall, Clarinda Mac Low, mayfield brooks,and Emily Johnson

While our politicians and corporations seem hell-bent on degrading the environment, there are dance artists in the New York area who are highlighting our essential connection to the earth. They are dedicated to tackling climate change, promoting sustainability, and engaging with their communities to raise awareness. While there is no guarantee that any form of performance can put a dent in the increasing assault on the planet, these artists remain deeply committed to making a difference. Within the genre of environmentally conscious works, three recent issues have surfaced: plastics, birds, and water. And, everything is connected to everything.

In September, Edisa Weeks and her Delirious Dance created WASTELANDIA, an epic happening in five galleries of The Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art at the Snug Harbor Museum on Staten Island. Weeks unleashed her imagination on the basic question of how, in her words, “we can be better stewards of the earth.” In one gallery, a crawling blob of black plastic bags rose up into a leafy monster. When the creature started shaking, it was both funny and scary. Then it twirled, thrashed around, calmed down, and gave a small object to the humans in the vicinity. At another time several dancers grooved to a rhythmic beat, using empty plastic bottles as part of the percussion ensemble. In another gallery was the interactive Plastic Tunnel, which Weeks says represents the five massive patches of plastic debris that have accumulated in the ocean. In still another location, she arranged for local activists to create seven murals that dramatize our dependence on fossil fuels.

Reviewing an earlier version of WASTELANDIA, Toussaint Jeanlouis of "The Dance Enthusiast" wrote, “Through craft-making, visual art, theater, and dance, the audience is taken on an interactive journey to witness a land that can be sculpted, destroyed, and rebuilt again… with more plastic.” Jeanlouis praised “the intelligence, detail, and heart that Edisa Weeks puts into her work.”

It's no easy feat to present such multi-layered spectacles. As Weeks, a Scholar in Residence at The New School with a long track record of addressing social justice issues, told me in an email, “Venues and presenters are presenting less dance, and are not taking risks, especially with politically based work.” Weeks is happy that the community murals she organized will return in 2026 for the opening of Staten Island Urban Center's new home.

Also concerned with the destructiveness of plastics is Jody Sperling and Time Lapse Dance. As the Eco-Artist-in-Residence at The New York Society for Ethical Culture, Sperling offers free outdoor performances, school shows, and workshops, all focusing on ways to engage with climate action. At various festivals in New York, she has made art out of our extravagant waste of plastic bags. For her piece Plastic Harvest, she and her dancers paraded in the street with their over-the-top flouncy outfits made from hundreds of plastic bags. As Tom Phillips wrote in these pages, “The dance dramatizes not just the ubiquity of plastic bags, but also our comfort with them.”

Sperling has long been intrigued by modern dance forerunner Loie Fuller, who conjured illusions of nature—a lily, a snake, a flame—by swirling yards and yards of silk with long wands. Sperling taught herself Fuller’s technique, applying it to climate issues. In doing so, she joined aesthetics to what she calls eco-kinetics. As a dancer, she can imagine a congruence between the human body and the earth body: “We deploy dance to awaken the senses to atmospheric change, to confront our climate grief, to build community around climate resilience and to facilitate action.” One of her most visually arresting, projects was her dancing on the Arctic Sea Ice, in which she asks the question, How can we use patterned human movement to understand melting ice? She has spoken out about the role of art in social change. “We’re living in a perilous time,” she said in this Earth Creative podcast, “and when we band together, our voice is louder and we have a broader impact.” During the upcoming APAP conference, she will present two previews of a new work on January 9 and 10. And for Earth Day week this spring, Time Lapse Dance plans a retrospective on April 24 & 25, 2026.

Both Jennifer Monson and Jill Sigman have called attention to migratory patterns of birds and what that can tell us about the environment. In 2000 Monson started channeling her craze for—and mastery of—improvisation into her concern for the environment. She formed iLAND (Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Art, Nature and Dance) to promote cross-disciplinary collaboration surrounding urban ecology. One of her projects was Bird Brain, in which a small group of improvisers navigated along the migration paths of birds and whales. In an interview on this site, Monson said, “We primarily used our sensory experience to perceive the world around us and danced in response to our observations.” This multi-year project produced a manual called A Field Guide to iLANDING: Scores for Researching Urban Ecologies.

Sigman’s aesthetics center around the beauty of natural materials, while her activism calls out our wasteful habits. She has done this with humor and whimsy, as in Our Lady of Detritus in 2009. Her recent Spark Bird was created in partnership with the Feminist Bird Club of Jersey City at the Smush Gallery. Although the nature component of dried plants and bird’s nests looked lovely, they were contaminated with chromium, reminding us that pollution is everywhere. Just this fall, Sigman performed a new version of Spark Bird in the Soon Is Now festival, a climate-themed arts series in Beacon, New York. For this event, Sigman and her dancers engaged the audience on a walking tour along Scenic Hudson’s Long Dock Park.

Also performing at the Soon Is Now festival last fall was Davalois Fearon, who brought her 2017 piece Consider Water. With four dancers and four musicians, this dance is based on her personal experience of limited access to water in her home country of Jamaica. Reviewing it in "DanceViewTimes", Mary Cargill wrote that it “was a haunting reminder that Americans are so lucky to be able to take our water for granted, turning on a tap without effort." To accompany the piece, Fearon publicized four alarming facts: “One in nine people around the world do not have access to clean drinking water. Over 90% of disasters in the world are water-related in terms of number of affected people. In America, 40% of the rivers and 46% of the lakes are polluted and are considered unhealthy for swimming, fishing or aquatic life.”

Another group immersed in water issues is the Brooklyn-based Artichoke Dance Company. Their program Moving the Rights of Rivers according to their website, perform with the goal of “bringing arts, environmental, education and activist communities together.” Director Lynn Neuman partnered with Governors Island to form the interdisciplinary Eco-Arts Festival during Climate Week in September. Besides organizing events like children activities, Neuman presented excerpts from her work Within the Waters. In this recent interview, Lynn says that Within the Waters “addresses the legacy and memory that water holds.” Like Sperling’s Time Lapse Dance, artichoke too will present excerpts at APAP on January 9 and 10.

Carolyn Hall, who is both an ecologist and a dancer, is part of the interdisciplinary organization Works on Water (WoW); she collaborated with Clarinda Mac Low (collectively Sunk Shore) in WoW’s Triennial Exhibition on Governors Island this fall. The Triennial addressed water and the climate crisis during Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s River to River Festival. As part of the Triennial, twice a week since May, small WoW teams have also been doing their Walking the Edge project—walking as many of the 520 miles of NYC shoreline as possible “to understand how much of the New York shoreline is accessible, how much is industrial, and how much might be dangerous for humans.” Hall says that their actual presence at the water’s edge makes a difference. “By putting your body in the experience of all the different kinds of shoreline and realizing who lives there by choice, who lives there by necessity, and who can't live there,” she says, “you have a very different relationship” with the coast and local communities.

Of course, here in NYC we have nothing to worry about in terms of water, right? Wrong. Hall points to two issues facing New Yorkers. The first is the steady sea level rise. According to Hall, the rise “affects our infrastructure, our transportation, our housing, our electricity...By 2100 our sea level could be six feet higher than it is now and would flood a lot of our shoreline.” The second is our drinking water. We’re lucky in that the water entering our Croton Reservoir is naturally filtered, but climate heat will weaken that process over time.

As they walk the shoreline, Hall and friends encourage people “to think about what else lives with and under the water, to think about how they're treating it. So it's literally being a body in space, drawing attention in a way that is effective. Often the effectiveness is in making the information very local. The hard part is, how do we make it global?”

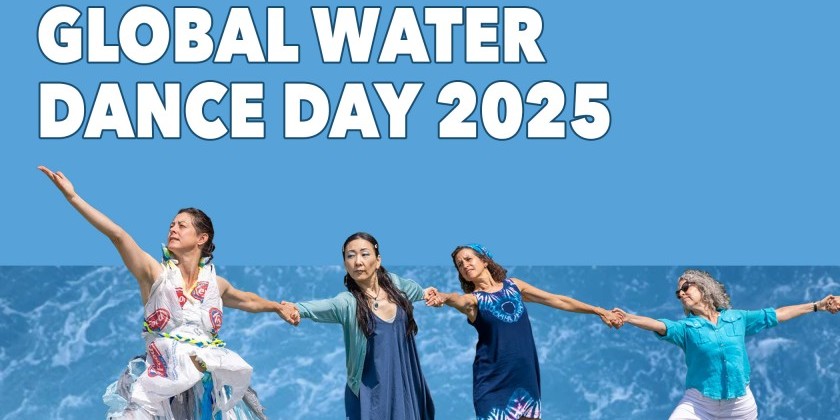

To answer her own question, Hall tells me about Global Water Dances, a growing network that produces annual events all over the world. Through dance, they tackle issues of water scarcity, pollution, fracking, or natural disasters, especially when partnering with local environmental groups. This beautiful documentary from 2022 celebrates ten years of Global Water Dances. In 2025, participants included 137 sites from 39 countries on 6 continents. Karen Bradley, one of the GWD founders, says that “being connected up globally, we begin to see the enormity of issues, including our own, and how the patterns of crises link up.” She adds that she personally finds the African and South American projects to be especially impactful.

Dance makers can come to this work from many different angles. mayfield brooks had been an urban farmer in the Bronx, very involved in the cycle of composting. They have said that “the compost was somehow informing every aspect of my life.” In 2023 they made Wail Fall/Whale Fall which connected the decomposition of a whale as it feeds other species (aka composts) to the process of grief and release.

Dance artist Emily Johnson and her company Catalyst are concerned with indigenous rights and traditions. Her 2022 piece—or rather “performance gathering”—at New York Live Arts, Being Future Being:Inside/Outwards, was called transformative by Dance Enthusiast writer Catherine Tharin. In this impression, Tharin describes the awe she felt as one who was invited to participate onstage. “Johnson has brought us to a different place altogether where each tree, animal, rock, flowing stream, and star is oracular. . . It's a compelling vision.”

I hail the dancemakers who are passionate enough to overlook the logistical and financial barriers in order contribute their creativity to a sustainable vision for the planet.

Created in 2020 as a way to lift up and include new voices in the conversation about dance, The Dance Enthusiast's Moving Visions Initiative welcomes artists and other enthusiasts to be guest editors and guide our coverage. Moving Visions Editors share their passion, expertise, and curiosity with us as we celebrate their accomplishments and viewpoints.