THE DANCE ENTHUSIAST ASKS: Catherine Gallant on "GIFT: A Life In Dance"

Acknowledging a Career Filled with Inspiration, Creativity, Curiosity and Versatility

On January 23rd and 24th, at 280 Gibney, Agnes Varis Performing Arts Center in downtown New York City, GIFT: A Life In Dance will exquisitely mark the 70th birthday of dance artist Catherine Gallant, a multi-generational offering accompanied by live music, film, guest artists, and performed by her two companies, Catherine Gallant/DANCE and Dances by Isadora. These evenings honor not only Gallant's decades-long career as a performer, choreographer, teacher, and leader in dance education, but also her valuable work as an interpreter and standard-bearer of Isadora Duncan's dances.

Recently, I had a chance to meet over Zoom with this soft-spoken, thoughtful artist for a chat about her upcoming performances and the wide-ranging experiences and creative voices that have shaped her artistry.

For tickets and info, visit Eventbrite

Christine Jowers for The Dance Enthusiast: I have known you for a long time, yet it seems that only yesterday The Dance Enthusiast was covering you in A Day in the Life of Students and Teachers — Catherine Gallant at PS 89. That was 2008. Where does time go? And you're 70 already? Happy birthday. Is this concert a celebration?

Catherine Gallant: I mean, "celebration" is a word people use. I say it's more "acknowledgment." It's what I love to do best. That's what I wanted to have as part of this — the moments, the moments of moving and dancing and creating.

How were you first introduced to moving and dancing, Catherine?

I always danced myself. It was a very solitary thing that I just did. I thought I invented that [Duncan] way of moving with nature! I was allergic to what was happening outside, seasonal allergies, so during school, I was allowed to go to the library and spend a lot of time by myself, which I liked because I also had strong social phobias, and didn't speak outside my home until I was around twelve.

Then, in the library, during the sixth grade, I found Duncan Dancer, the Irma Duncan book. It was so important to me. I had no idea what I was reading about. It was that kind of "being -in-a-place-finding-something-you-don't -know," so you create a version of it in your imagination.

Was your family concerned that you never spoke?

A little bit, but mostly, people on the outside did not understand it. And in those days, there was no understanding of what we might call selective mutism or anything like that. It was just like, "Hey, what's the problem here? Cat got your tongue?" When I heard that, I was never going to talk. I was a little difficult.

I was also around 12 years old when, after school, I started going to a social dance class. And what happened? I realized that I could put the responsibility of the dancing on my partner, [as if I] wasn't really doing it. But, I was doing it, and I was enjoying it: the Cha Cha, the Foxtrot, whatever. That was back in the very binary days. So, that helped me. And shortly after that, my parents found a dancing school.

I've seen some of my students go through this, where dance allows them to have a voice, literally their voice, especially if one is in that pathologically shy category.

How did you know you wanted to make a profession out of this?

In fact, it was when I learned to drive around 16 or 17. I drove to Providence, Rhode Island, and saw that there was a dance performance at Brown University. That was the first time I saw what we think of as modern dance. Julie Adams Strandberg, Carolyn Adams' sister [who was the founding director of dance at Brown University], taught there for many years and put on an amazing program of modern dance. And I thought, Oh, this is it. This is what I want to do.

I ended up at Boston Conservatory, where they taught Graham and Limón, and a smattering of Cunningham. And that's where I also started making dance. We studied composition. We must have studied ballet pedagogy; there was no teaching the art of dance in other ways. Then, teaching, of course, was something I wanted to do, but the reality is that you have to do something to live, right? I feel fortunate that I was able to make a living teaching, and teaching helped me to have a life in New York City.

When did you start investing yourself in Isadora Duncan's work?

That was 10 years later. I was graduating, toward the end of my time at the Boston Conservatory. I was at home, folding laundry, when I saw Annabelle Gamson on Dance in America on Public Television. I thought, wow, this is really interesting, and cataloged it away. When I came to New York, I wasn't seeking it out, but there it was. And I went and started studying.

Seeing Annabelle Gamson, I was watching this amazing, mature artist, pounding fists and screaming —all of those strong dances — but when I first saw some of the [Duncan] work in New York, I saw a lot of skipping around. Wow, a lot of skipping! As I entered it, I realized there are other energies, movement qualities, and a whole world of connections to history and the development of modern dance there. Initially, it felt like how I started dancing as a kid, by myself outdoors, and that's why I liked it. I didn't think of it as I'm going to enter this and, you know, learn every dance, and it's going to be part of my fabric, I didn't. It was just for fun, and then I kept going.

Catherine Gallant. Photo: Melanie Futorian

Was there any particular Duncan teacher or artist who spoke to you?

Julia Levien, because she was a choreographer herself, and she had invested a lot of time in the social and political history of the work. I appreciated all the commentary she could bring as she coached and taught. She was, in fact, my first teacher. I attended her workshop in 1982 after her husband had passed and she was looking to, you know, reactivate. She was very active in the late 70s, during the centenary of Duncan's birth.

But it was also Annabelle Gamson around that time, in 1976 and '77 [who inspired me]. She had a wider, national presence and brought her own very distinct artistry to the work. She studied with Julia as a child, then went on to dance with Agnes de Mille and Katherine Dunham. Imagine, she had this amazing Broadway life! Duncan became popular and recognized with Gamson, but it was Julia Levien who taught Annabelle Gamson and many of us.

Julia studied with Anna and Irma Duncan, primarily because those women came to the US and worked, especially in New York City. Julia came from the kind of Jewish intelligentsia in New York City, families that wanted their children, their girls, to study art, history, and politics. She was brought to Irma's school very early, like five or six years old, and then, as a teenager, she danced in many performances and learned a large amount of repertoire. What I really appreciate about Julia is that, toward the end, when she was in her 80s (I met her when she was 72), she restaged a number of dances that would have been completely lost. That was a significant contribution that she made.

Do you feel a particular responsibility to the Duncan work?

I'm interested in the responsibility of questioning Duncan's work. I don't think the dances will be lost. Many people have felt the responsibility and passed them on in their own way. I want to crack that open and make sure that [the Duncan work] is shared very widely, with people from other areas and disciplines within dance or otherwise. I'm also interested in shifting some of the musical choices to bring things into a more contemporary relevance. I have done that a bit over the last few years; I feel my responsibility is to keep the work relevant and valuable to students of dance. I've gone into quite a few college and university dance departments where I present a Duncan dance, then students create their own response to it. I'd like to see [dancers] step in as a way to explore the work, not by saying, "I'm a Duncan dancer, and this is a definitive example of the work," but, "I'm a curious mover."

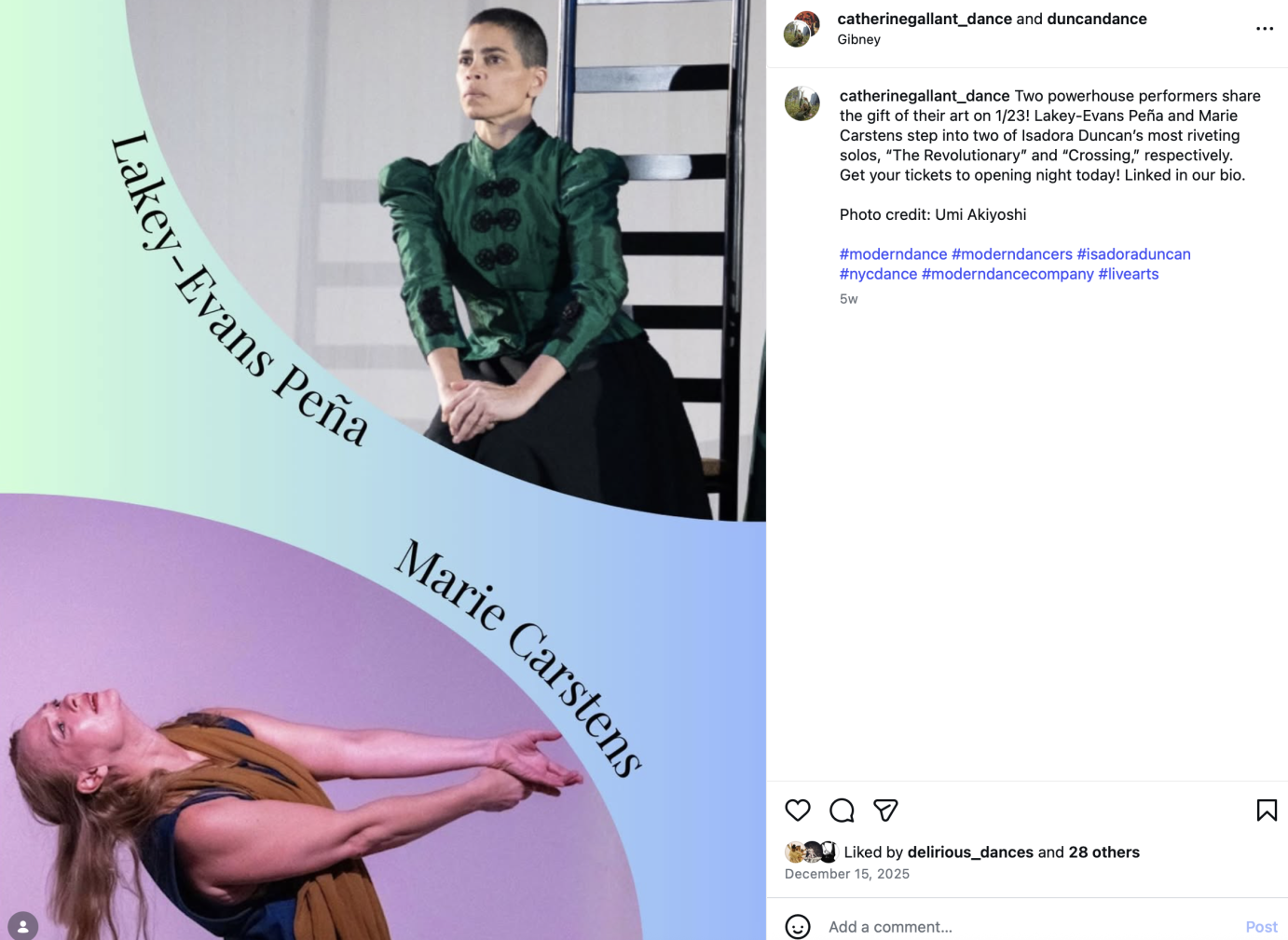

So, for example, in this upcoming show, on the first night of the performance. Duncan's "Revolutionary" will be performed by Lakey Evans-Peña, a curious mover with a background in the Horton technique. And then Marie Carstens will do what we call The Crossing. She originally studied with another Duncan legacy holder, Jeanne Bresciani, who comes from the Maria Theresa legacy line. We're very much related, but if you dive deeply into this work and know the different lines, you'll see that there are various versions of the same dance, and people speak about the movement a little differently. Marie went on to become a dance therapist/expressive therapist. She brings a lot to the work.

And your choreography? Tell me about your choreographic mentors.

When I moved to Manhattan, I spent about eight or nine years studying with Anna Sokolow. She had workshops that would last 10 or 12 weeks, at the New Dance Group Studio, the Abraham Goodman House on the West Side, and ultimately, at Mary Anthony's studio on Broadway. We would start with maybe 20 people, and by week two, there'd be 10, because she had uncompromising standards.

"What does it mean?" It had to have a certain sense of connection, emotional connection, and meaning, according to her vision, and if you were somehow not approaching that, she would be very clear with you. She wouldn't ask you to leave, but she would just say something like, "Well, that seems like you're not serious."

For some people, that felt like a rejection, and they didn't continue. That was a different way of teaching. Back in the day, they were the master, and you, as the student, were there to submit to this vision. We don't really work like that anymore. It's a more collaborative, right? She didn't do that.

Even though it was hard, you knew you were searching for something that she would say was the truth. And though that still seems quite abstract to me, I knew somewhere, even though I couldn't articulate it, I knew what she meant, and I was happy to learn from her and to seek that. That time spent with her was very important for the kind of self-reflection and questioning that artists have to do.

I know you will be presenting Isadora solos danced by you and guests, video excerpts of past works, a premiere video montage called Memoir, as well as a solo you created for yourself last year, STAND, but tell me about the quintet Late Echo, which you chose to show as part of GIFT. Is it one of your favorite choreographies?

I made this piece when we were still unable to get into studios together in 2022. I started with Zoom rehearsals and gave myself an assignment. I was not going to spend more than 40 hours on the project. 40 hours of rehearsal, including performance. I probably cheated a little with my preparation time and went over that, but I was trying…

We started online. I started with a lot of investigation and exploration, and came into those Zooms knowing what I was going to ask people to try, and they did. And then it was commissioned, actually by my friend, Francesca Tedesco, for her group.

When we were finally in the studio, we started playing around more. I would say that I was influenced by the work of Merce Cunningham, allowing chance to enter and allowing indeterminate structures. I based the dance on three rhythmic patterns: four, seven, and nine.

I want it to always be unpredictable in some way, as you're watching it. Unpredictable and unexpected, as far as the trajectory, the quality of the movement, the use of space, and how people enter and exit.

I don't know about favorite… but I must like it, because this is our sixth time doing it. Even as I watch it now, it has so many layers.

You've taken on so many roles in the dance world. Still, most particularly, you have been quite involved in education as a dance teacher to professional artists, university students, and, for 25 years, in the NYC Public School system. The documentary PS Dance! featured you and your PS 89 students, and you served on the writing committee for the NYC Department of Education Blueprint for the Arts in Dance? How does all your education work influence your other dance work?

Influences shift and change, and get mixed with everything else that happens, that comes in, whether through literature, film, or life experiences. Teaching — I learned a lot from my students; children are these untrained artists. I would see amazing ways that my students went to the floor and got back up again — unpredictable patterns.

As a teacher in a room with students, especially children, it's an opportunity to ask questions. Rather than saying, "Okay, now we're going to stand up." We explore. "Okay, we're going to stand up slowly, and we're going to stand up with our elbow first." What I want to mention is that all this stems from my work with the Dance Education Laboratory (DEL) - Dance Education Courses. Almost 30 years ago, in 1996, I was there with Joan Finkelstein at the 92nd Street Y, at its inception. That was a huge influence on my teaching and on my other dance work, because of the ability to deconstruct and put things back together, to look at the essentials of action and all the ways it can be modified.

I remember, not so long ago, before I retired, I would use my camera (my students had permission to be filmed). I captured this boy doing what he was doing, brought it to rehearsal, and asked my dancers to learn it because it was terrific. I took a lot of movement from my students. Sometimes I would tell them, “I put that in a dance, you should come see it."

That must have been a big boost for them.

I think they were mystified and had no idea what that meant. But that was a way of saying to them, "They're people in the world who are choreographers. They make dances. They think in movement. And sometimes they look out the window, see something really interesting, and put it in their dance."

Tell me about the live music in your concert.

There is the live music component, which I am really happy about. I've known Alan Moverman, the pianist, for 30 years. He credits his connection to dance — now he's also been with New York City Ballet for 30 years — to playing both in the studio and on stage in Duncan shows I was part of.

And Lakey Evans-Peña, how did you connect with her?

It was during the project that came together because I had done some curriculum writing for the Ailey organization. I wrote the curriculum for Night Creature and the study guide, and [I was tasked] to help at the beginning of the Ailey Teacher Certification Program: Ailey Horton Technique. That's how we started working together. Whenever I do a project like that, I learn a tremendous amount about dance history. Lester Horton, I didn't know much about him. I did a deep dive into that history and into how he talked about his technique.

Just hearing about you putting together the teaching program for Night Creature —what a fascinating job. It sounds like you're a sleuth, investigating, but not really a sleuth. a researcher, an archeologist-

A nerd, really a dance nerd. Learning about historical time periods and how they intersect, and the influences of one dance visionary over others, and all that patchwork of dance history. I don't call myself a historian, but I'm interested in understanding all those connections.

I just finished a 17-lesson curriculum for the Dance Theater of Harlem's new Firebird. That was a whole other learning about Arthur Mitchell and how Dance Theater of Harlem started. I so enjoy doing those projects.

You've had almost every kind of job one can have in the dance field. Is there something that you want to do that you haven't done yet?

I want to be a supernumerary at the Met. Oh, my, that stage. I've never danced on that stage. I can pretend I'm singing. Well, I'll do whatever they want. I get to wear a big costume. I get to stand in the darkness in the wings and come out there. Wouldn't that be great?