IMPRESSIONS: Dutch National Ballet at New York City Center

New York City Center presents

Dutch National Ballet

Artistic Director: Ted Brandsen

Artistic Associate Director: Rachel Beaujean

November 20 - 22, 2025

-

Program A, viewed November 20 at 7:30pm

-

Program B, viewed November 21 at 7:30pm

An ensemble work by artistic director Ted Brandsen opens the four-performance season of the Dutch National Ballet at New York City Center in November, 2025. After a moment in a spotlight, a single woman finds herself surrounded by a cluster of onrushing people all clad in white, unisex dresses that swing freely from tightly fitting leotard tops. The 18 dancers (nine women and nine men) soon form concentric circles, and eventually execute a canon in three, front-facing lines of three couples each. A step-tap, step-tap pattern repeats, and a cluster forms that briefly reminds me of Alvin Ailey's Revelations. A blurred Rose window is the sole lighting ornament placed high in the center of the otherwise black backdrop.

Brandsen choreographs to the music of John Adams, and presumably as a nod to this eminent American composer, uses the title of the composition, The Chairman Dances. Since the dance work premiered in September 2023, I wonder if Brandsen anticipated the US engagement of his company. It certainly comes across as a respectful gesture to the United States of America to open his company’s season with Adams’ work. The piece also shows respect for the art of dance as a sanctuary and as a safe haven for community. Yet it serves as a joyful, presentational opening dance built on a solid foundation. Brandsen does not comment on the jazzy overtones. He restricts his choreographic explorations to revisiting canon patterns, while the diatonic harmonies perhaps invite a more multi-colored response. Does the respectful and calculated movement grow stale? The brevity of the composition saves it from itself. The group retreats, and a man lingers for a couple of seconds with the female dancer who opened the evening. Then he also retreats, and she is left alone.

“The house of able dancers” would have been another apt title, and I hope for more excitement and risk-taking in the works to come. Yet somehow I feel safe with the company in Brandsen’s hands. His choreography shows me that he cares about his dancers. The Chairman Dances is a piece by a director of dancers, rather than a choreographer. He will retire from his position at the end of the 2025-26 season. Ernst Meisner, currently the director of the company’s junior troupe, has been named as his successor.

The bare torsos of Timothy van Poucke and Conor Walmsley delight in Two and Only, a NY premiere by choreographer Wubkje Kuindersma from 2017. Composer Michael Benjamin sings live, and accompanies himself first on the guitar, and then on the piano. The change of color in the music enlivens this male duet that starts out as a solo, and then morphs into an intimate partnership that allows the dancers to travel through the space together. Lifting a partner around the waist to get ahead in second positions signals a confident stance. The second dancer leaves just before the end of the work, making me think about the weight of this relationship, and I realize that I care.

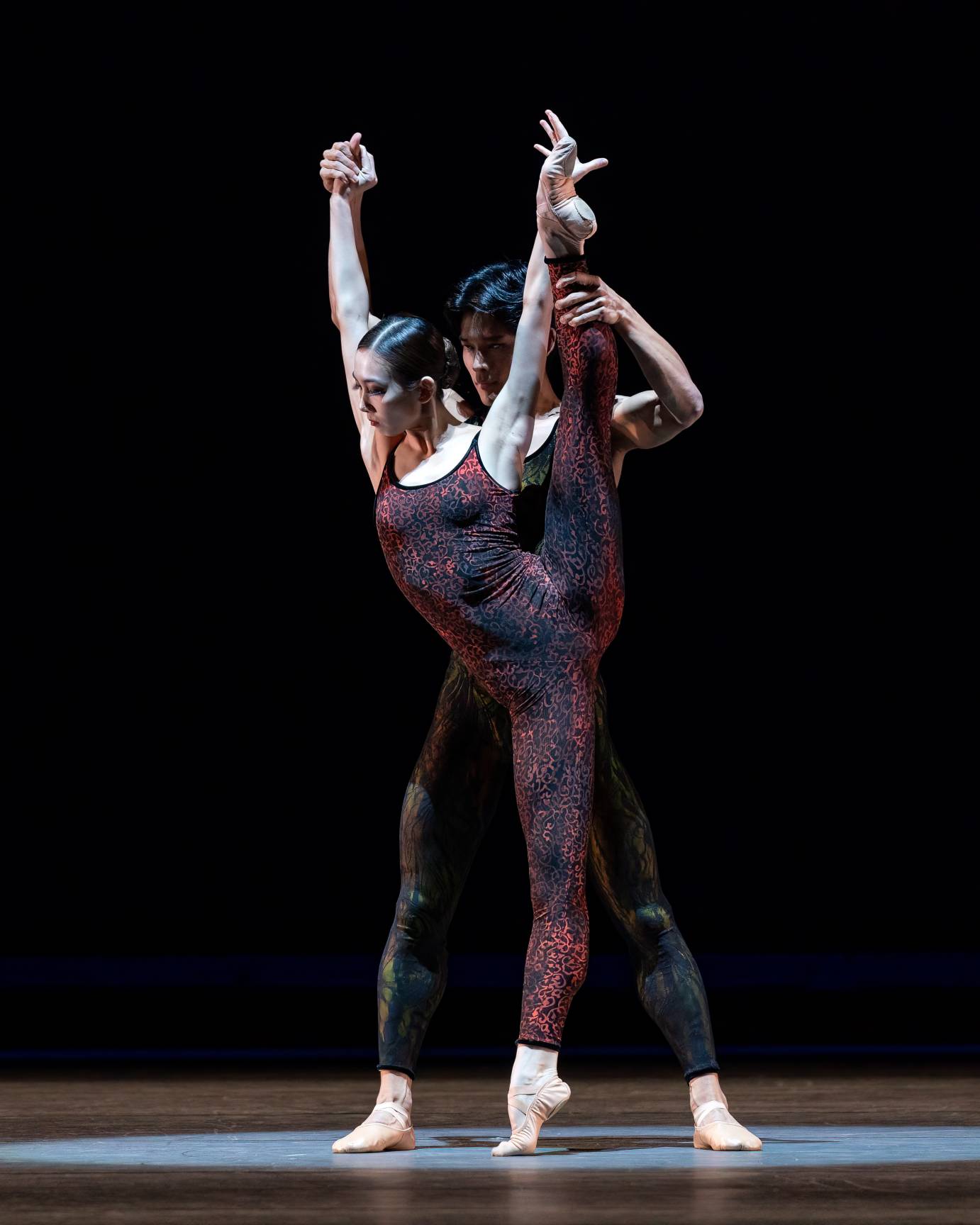

Jerome Robbins choreographed Other Dances for Kirov defectors Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov, for a gala benefiting the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, in 1976, at the Metropolitan Opera House. Robbins’ homage to the Russian style of ballet only entered Dutch National Ballet’s repertoire this June. Acquired for the Kirov-trained, ex-Bolshoi ballerina Olga Smirnova and her Italian, Bolshoi co-defector, Jacopo Tissi, it receives an uneven performance. Handsome Tissi, who was an ardent Romeo to Smirnova’s Juliet in a recent Fall for Dance program, gets caught up in playing to the audience. His long legs still impress me, and so does the rest of his physique, but he appears light when he should be grounded, and performs without a purpose driving him. To me he looks like a gorgeous tree without roots. I admire his beauty, but I worry about a lack of stability.

Smirnova lets my eyes rest on her. The sculptural clarity of her movement travels harmoniously through space. Her eyes, often cast downward, belie the alertness in her neck. She fills the frame in every angle she creates with her limbs, while her gestures open imaginary doors in her quest across the floor. She softens in Tissi’s presence, and she relies on her steely technique to make one believe she dances with abandon. It’s a masterclass in how an understated, or rather inwardly focused performance can resonate powerfully, when delivered with ease, musicality, and a sense of never-ending weighted flow.

My companion comments, “she is lovely.” To me, Smirnova brings Frédéric Chopin's music into her dreamworld. She shares her dreams through her melodic movement quietly, yet memorably with her partner and with her audience. The excellent pianist Ryoko Kondo facilitates this dream.

After an intermission, Trio Kagel tries extremely hard to be funny. Old-fashioned, cringe-inducing ballet humor that incorporates moments of mocking street dance embarrasses dancers and audience. On a positive note, one moment is worth remembering: while sitting on Giorgi Potskhishvili’s shoulder, Lore Zonderman bends down and reaches out her arms to partner Kira Hilli in an assisted turn. Neither Potskhishvili, who pulls off multiple turns with astonishing ease, nor accordionist Vincent van Amsterdam can be blamed for this crime against the defenseless, late Argentine composer Mauricio Kagel. The program credits Alexei Ratmansky with its choreography.

Hans van Manen's Frank Bridge Variations, to Benjamin Britten's music, showcases two principal couples and a supporting sextet in unitards. The piece, created in 2005, proves that van Manen does not remain stuck in traditional gender roles. A favorite partnering moment occurs when a female dancer facilitates a male dancer’s arabesque promenade by grabbing his waist while she runs around him.

Van Manen creates a world that is not necessarily unisex, but the streamlined costuming and ballet slippers for all put the sexes on equal footing. Men still lift women, but everyone gets to explore and travel through the stage space. The weighted chassés with bent legs, and the V-shaped arms remind me momentarily of Paul Taylor, but van Manen juxtaposes the modern dance elements with elongated balletic lines. I enjoy the different groupings. The sextet makes way for a brief quartet that morphs into a pas de deux, which the female dancer eventually exits. A lone man remains, and during a solo in which he seems to celebrate his independence, he briefly sees other male dancers cross the stage. After he leaves, an ominous walking pattern introduced by one dancer picks up another member of the cast with each turn. The feeling is heavy. It’s an emotional time for the ten dancers, which they must weather together. Then the group leaves. A woman and a man remain on stage, look at each other, and embrace. A tenderly supportive pas de deux ensues.

Van Manen pays homage to Britten, who composed the variations on a theme by his teacher, Frank Bridge. The fine dancers Floor Eimers, Constantine Allen, Qian Liu, and Young Gyu Choi lead the cast, in which Luca Abdel-Nour catches my eye for his dynamic range, weighted gesture, and sculptural quality. When he darts across the stage with a clear focus, I just feel let down that he does not start singing Adolph Green & Betty Comden's lyrics “I can cook, too.”

The New York premiere of Frank Bridge Variations serves as a welcome introduction to van Manen’s more recent work on opening night. One of his widely acknowledged masterworks, the 1973 Adagio Hammerklavier, set to Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major, op. 106, opens the second program on Friday evening in a most convincing manner. Reportedly van Manen had not known of Balanchine's quote that “dance should leave Beethoven well alone.”

While Maurice Béjart tackled the composer’s monumental Ninth Symphony, in 1964, with a cast of many dozens, van Manen approaches Beethoven in a more private setting. A high curtain drawn closed across the backwall of the stage reaches only to mid-level. If there is a window behind the curtain, it will be forever out of reach. Yet a breeze from stage right gently moves the curtain continuously. This slight movement of the set (by Jean-Paul Vroom) infuses hope, and I imagine building a human pyramid to escape if necessary.

Thankfully the three couples respond to pianist Olga Khoziainova with finely tuned ears and bodies to match. The women dance on pointe, and designer Vroom puts them in lovely, light blue knee-length dresses, while the men are clad in simple white tights. Is it a gay or European twist that they sport shiny necklaces? Elle Woods, of Legally Blonde, needs to keep in mind that people in 1973 were probably more open-minded than our current world view would lead us to believe.

Yet the three pairings stay in the heterosexual realm. Anna Ol and Semyon Vekichko, Qian Liu and Constantine Allen, and Smirnova and Tissi glide through intimate, yet distinct partnering sections and unite in sweeping group movements. I can’t quite decide if the deep plié performed in unison by the three couples is supposed to be meditative; and when the women spring from it into supported arabesques, I am flummoxed by its awkwardness. But then I think of social pressure, and situations in which one feels uneasy, and I decide to accept the choreography’s idiosyncrasies. I follow the journey with interest, and by the third movement I am completely hooked. Smirnova and Tissi infuse slow motion with wonderment. Van Manen challenges the dancers to connect sparse movements through elongated breaths. Lines seem ever so slowly to wrap around space itself. These masterful dancers elevate movements that could feel disconnected if performed by lesser artists. Stillness is the breath of gods.

Anna Tsygankova and Giorgi Potskhishvili follow ballet’s tribal instincts and display virtuosity in South African choreographer Mthuthuzeli November’s pas de deux Thando, which premiered last year. Potskhishvili appears bare chested as a primal golden idol tasked with keeping Tsygankova busy. They look good but the movement-hungry Potskhishvili deserves more complex assignments.

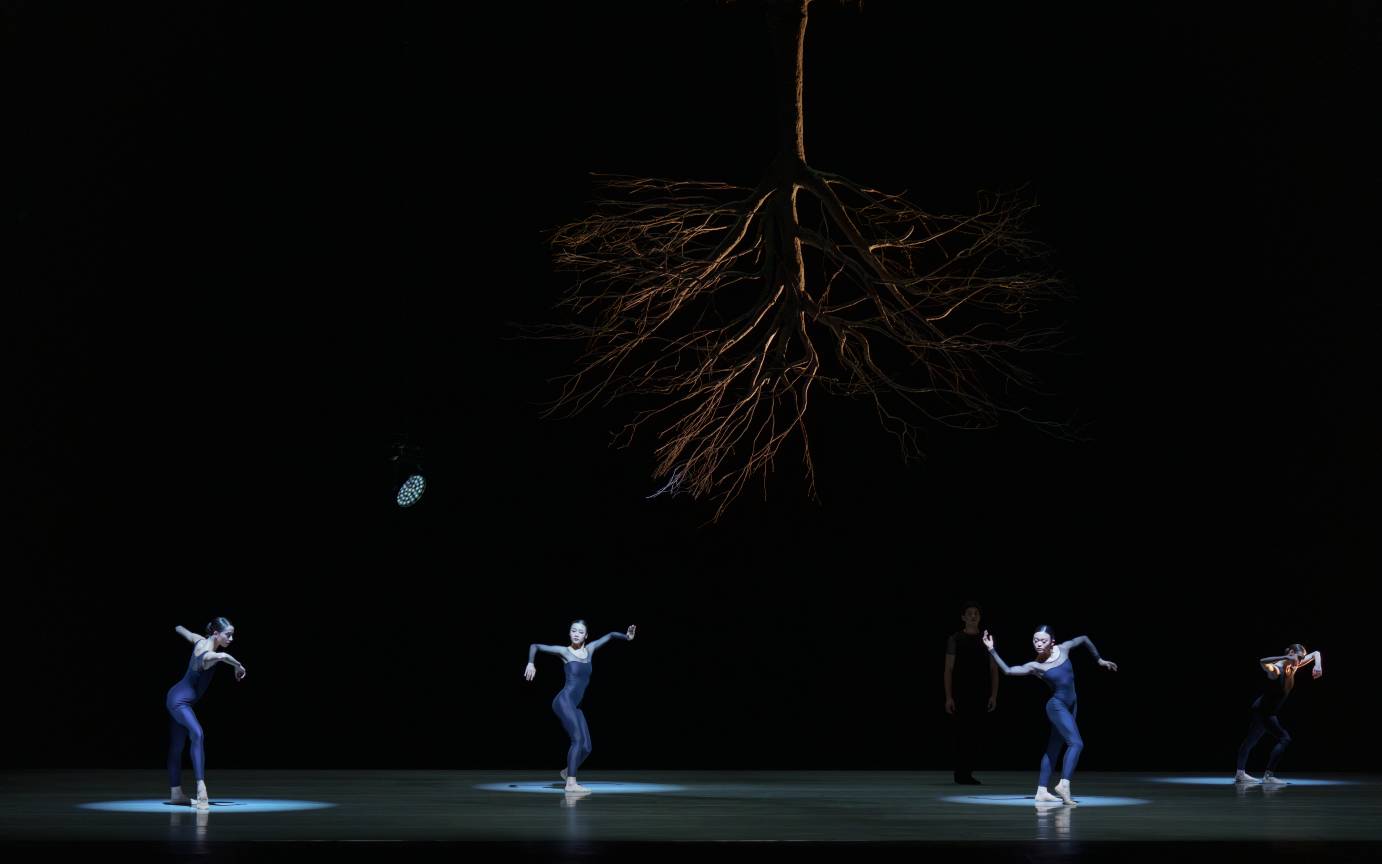

Jiří Kylián's intricate and beautiful Wings of Wax spirals into eternity. A tree hangs upside-down from the ceiling, and a lighting fixture slowly orbits around the space like an artificial sun. What would Galileo say? Just like the curtain in van Manen’s Hammerklavier, a set element moves with the dance. The title makes me think of the Greek myth of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun, and his father Daedalus, who had warned him. Other than the slowly circling lighting instrument, I cannot find any connection between this myth and the choreography, but no matter: I am mesmerized by the detailed directional attention to every limb. The work for eight dancers contains a pas de deux for Smirnova and van Poucke. The two connect seamlessly without looking at one another, and the slow spirals of their supple spines continue through their heads into space. It’s a transfixing and truly hypnotic effect; and I find my neck ever so slightly oscillating as the curtain descends.

In Wings of Wax, the collage of music by Heinrich von Biber, John Cafe, Philip Glass and J.S. Bach provides a wide range of dynamics and sounds. The memorable lighting and scenic design by Michael Simon, paired with sleek and simple costumes by Joke Visser, point to a meaningful collaboration between the choreographer and these designers. Riho Sakamoto, Jan Spunda, Yuanyuan Zhang, Edo Wunen, Koko Bamford, and Joseph Massarelli complete the remarkable cast of dancers. Originally premiered in 1997 by Nederlands Dans Theater, Wings of Wax was only acquired by the Dutch National Ballet last year. What a wondrous and magical addition to the repertoire!

Van Manen’s 5 Tangos closes the program. I get bored with it rather quickly. Is it too much of a good thing? Or did this piece from 1977 just not age well? Choreographed to music by Astor Piazzolla, the dance and the dancers never find a groove. Tango on point comes across as a misinformed Dutch appropriation of a beloved art form. As hard as I try to find redeeming qualities, I unfortunately only find poorly executed Ersatz.

While I enjoy the two programs for the most part, these evenings show that the ensemble contains dancers of varied skill levels. The repertoire surely boasts some masterworks rarely seen on these shores, but I would not be surprised if Argentina filed a “cease and desist” letter to stop the company from desecrating Kagel's and Piazzolla's music.