IMPRESSIONS: Pete Townshend's "Quadrophenia: a Rock Ballet," with Orchestral Score

Music & Story: Pete Townshend

Choreography: Paul Roberts

Direction: Rob Ashford

Musical Direction: Rachel Fuller

Orchestrations: Rachel Fuller, Martin Batchelar

Video Design: YeastCulture

Set Design: Christopher Oram

Costume Design: Paul Smith

Lighting Design: Fabiana Piccioli

Sound Design: David McEwan

Dancers: Paris Fitzpatrick (Jimmy), Seirian Griffiths (Romantic), Dylan Jones (Lunatic), Curtis Angus (Tough Guy), Yasset Roldan (Hypocrite), Taela Yeomans-Brown (Mod Girl), Harrison Coll (Friend), Adam Garcia (Father), Kate Tydman (Mother), Dan Baines (Ace Face), Ansel Elgort (Godfather), Amaris Gillies (Drugs), Jonathan Luke Baker (Psychiatrist), Jovan Dansberry, Anya Ferdinand, Serena McCall, Joshua Nkemdilim, Zach Parkin, Pam Pam Sapchartanan, Jack Widdowson

New York City Center, 131 W 55th St, New York, NY

November 14 - 16, 2025

A ballet adaptation of The Who’s 1973 rock-opera concept album Quadrophenia, written by the legendary band’s guitarist, Pete Townshend, Quadrophenia: A Rock Ballet is an exhilarating theatrical dance production. The word-less two-hour show debuted and toured in the U.K. earlier this year, then received its U.S. premiere at New York City Center in November.

However, what’s most interesting about the spanking new ballet is the opportunity it affords to revisit the historical sub-culture of the Mods, as the dance relates the coming-of-age adventures of Jimmy, an angst-ridden, 18-year-old Mod, suffering from schizophrenia. Yet as the altering of its sub-title suggests (across the pond the show was billed as Quadrophenia: A Mod Ballet) to fully appreciate the richly reminiscent period piece, American audiences may first need some background on that British youth cult known as the Mods.

Spawned in London in the early 1960s, Modernism was all about putting forth the details of a correctly fashioned appearance. One needed to look cool, clean, sharp, and wear neat stylish clothing (think, tightly-tailored suits and skinny ties), exude a hard-edged demeanor, perform jerky-moved pop-dances in fancy clubs until all hours of the night fueled by excessive amphetamine use, and ride around on flashy Vespas or Lambrettas, those sleek Italian scooters. The movement gained national traction when Modernists started appearing on television’s Ready Steady Go! (a British teen dance program similar to American Bandstand).

Possessed of highbrow cultural tastes (initially modern jazz), the Mods were essentially a movement of working-class youth, and soon embraced the earthier sounds of ska, American soul, and R&B. They ultimately grew more tolerant of less-refined behaviors as feelings of societal alienation and rebellious dissatisfaction began to dominate their mindset.

During the summer bank holiday weekends, most famously at Brighton in 1964, Mods assembled at seaside towns and engaged in violent conflicts with their rivals, the Rockers. A predecessor youth cult, like American “greasers,” the scruffy, black leather jacket and helmet-wearing Rockers rode bulky motorcycles and listened to rock ‘n’ roll. The Mods, on the other hand, preferred The Who. Though not originally a Mod band, The Who adopted Modernism and ultimately became the most prominent exponent of its style.

Though by the 1970s, Modernism had become passé, and The Who had shifted into new contemporary-rock territory (most notably with their 1969 rock opera Tommy), in an attempt to look back at his band’s formative years, Townshend penned Quadrophenia. Exploring themes of adolescent angst, tribalism, self-identity, mental ill-health, and youth’s extreme efforts to “fit in,” its story is set in London in 1965 and traces a short, tumultuous period in the life of its central character, Jimmy the Mod. The work’s title refers to the four competing strands of the schizophrenic teen’s personality, depicted in the ballet as distinct “characters,” named Tough Guy, Lunatic, Romantic, and Hypocrite.

While inspired by the album, the ballet also draws influences from Quadrophenia’s 1979 film adaptation, now a cult classic featuring the then-little-known singer-songwriter Sting as Ace Face, the alpha Mod of Jimmy’s group. It was the film’s popularity, amid a late-1970s Mod resurgence, that brought elements of the fashion-obsessed culture to the U.S.

In 2012, Townshend invited his wife, composer Rachel Fuller, to create an orchestral arrangement of Quadrophenia, and upon hearing it, he came up with the idea for a ballet adaptation. Fuller’s arrangement was recorded in 2015 by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and a 100-voice choir. That recording (minus the vocals) is the electrifying music to which the ballet is performed.

Directed by theatre choreographer-director Rob Ashford, the two-act narrative ballet is choreographed by the English dance artist Paul Roberts, best-known for staging commercial pop-music shows. Battling cancer during the making of the ballet, Roberts saw the work’s June opening in London, before he died on September 26 at the age of 52. In dedication to Roberts, Townshend brought the ballet to New York “on his own dime” and American audiences, Mods-aware or otherwise, will no doubt find contemporary relevance in its larger themes of teen-age troubles.

At the outset of the ballet, we meet the frustrated Jimmy living (still!) at home with his parents, undergoing psychiatric therapy, working a dull assembly-line job, and hanging out with his Mod friends, clubbing, doing drugs, and chasing girls. Always amplified by his schizophrenia, Jimmy’s frustrations intensify when he discovers his old childhood friend has become a Rocker (who later gets beat up by a gang of Mods), is humiliatingly rejected by Godfather, a celebrity musician he admires, and finally consummates his relationship with his love interest, Mod Girl, only to see her go off with another guy.

He then quits his job and gets kicked out of his parents’ house. Oh yeah, and his precious scooter is destroyed during the Mod-Rocker riots at Brighton. But the final straw is discovering that Ace Face, his Mod idol, spends his days working as a lowly bellhop at a fancy hotel. Driven to renounce Modernism and into a suicidal state that brings him to the top of a high seaside cliff, as the ballet reaches its climax, Jimmy wrestles with thoughts of ending his life.

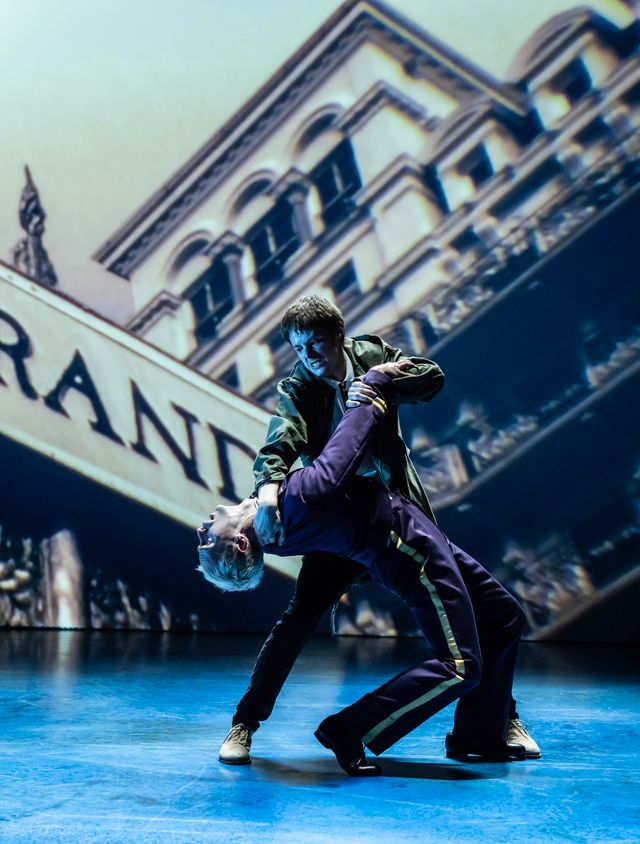

Roberts’s contemporary choreography (there’s no pointe work in the ballet) effectively tells Jimmy’s story via modern vocabulary motivated by a pliable use of the torso that makes for rich emotional expressiveness. Smooth body movements are accented by balletic leg lines that lend a clean sharpness, literal gestures that drive the narrative, and Mods-referencing pop-dance moves that entertain and contextualize. But most amazing, is how coherent and natural it looks emanating from the dancers’ bodies. We are not aware of the assembly and performance of a choreographic language, but find ourselves watching, instead, as we would a play, caught up, not in the execution of dance movements, but in the overall dramatic action being conveyed.

Yet the ballet’s storytelling success is not solely a choreographic achievement. Even in the absence of lyrics, with its full symphonic sound, bold dynamics, booming percussion, and delicious array of instrumental timbres, the music alone goes a long way toward communicating the drama. Sometimes, what we’re hearing is more interesting than what we’re seeing, and it can feel as though the music is the star attraction and the dancing is the “accompaniment.”

The show’s ensemble choreography is expertly crafted — particularly the stylish dancing of Mods at a nightclub, and the synchronized motions of factory workers that morph into acrobatics at “break time” — and one wanted to see more of that. The solo passages, however, often go on too long. At times, it looks like Roberts ran out of movement ideas and was just “filling the music” with repetitive activity. Nonetheless, we remained transfixed, because the show’s technically wowing dancers also display terrific acting skills.

Paris Fitzpatrick gives a tour de force performance in the demanding role of Jimmy, and Dan Baines (sporting blond, spikey hair resembling Sting) is delightfully charismatic as Ace Face. New York City Ballet soloist Harrison Coll, as Friend (Jimmy’s old pal-turned-Rocker), provides some of the show’s finest dancing, especially in an affecting duet with Jimmy, choreographed on and around a park bench. And most imaginative is the casting of the leggy, irresistibly gorgeous Amaris Gillies as Drugs. Glitteringly costumed in blue and lavender, she seductively manipulates the young Mods, as she portrays the colorful amphetamine pills they over-consume. The cast’s only weak links are Taela Yeomans-Brown, whose oddly dispassionate performance as Mod Girl dampens the heat of the character’s sexy choreography with Jimmy, and Ansel Elgort, whose limited dance capabilities make his a boring, air guitar-miming portrayal of Godfather.

Contributing immeasurably to the ballet’s persuasive storytelling are its elegant visual-design elements. Not only do Paul Smith’s costumes demonstrate the natty appeal of Mod clothing, but Christopher Oram’s efficiently symbolic set pieces combine with Fabiana Piccioli’s moody lighting and YeastCulture’s stunning video projections to believably evoke the show’s many and varied locales. Animated by video images of lapping waves spilling across the stage floor, the shoreline settings are breathtaking.

Doors adorned with the iconic red-white-and-blue Mod target are thrillingly integrated into the choreography as Jimmy and his four personalities (athletically danced by Seirian Griffiths, Dylan Jones, Curtis Angus, and Yasset Roldan) tilt, climb upon, and dance daringly under and about them in a risky quintet. And a crammed train car looks like it’s really in motion as streaks of light appear as changing scenery whizzing by outside the windows.

Despite its dramatic clarity throughout, the ballet ends ambiguously. After a protracted “will he or won’t he” scene — in which we watch a suicidal Jimmy execute the same movements repeatedly, rushing to the edge of the cliff and then retreating, our interest held only by the music and Fitzpatrick’s acting — the production (finally!) ends as Jimmy jumps off the cliff, plunging to his death — or maybe not. A few seconds later, his face emerges, and we see him struggling to pull himself up from behind the rock. Even though it’s located on what’s surely the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum of story ballets, as I watched Jimmy maneuver to the stirring music, I found myself recalling the dramatic, Tschaikovsky-fueled ending of Swan Lake — when the lakeside lovers jump to their deaths and then re-appear, rising above the stage on route to an otherworldly realm.

Here, we’re left with an image of Jimmy, undefeated by his “troubles,” and on his way to recovery. But will he triumph in a healthy return to this world, or only in some sort of afterlife? The interpretive choice is left to us — aptly, I think, as we all need to spend some time thinking more deeply about our collective role in the alarming decline of the mental health of many of those coming of age today.